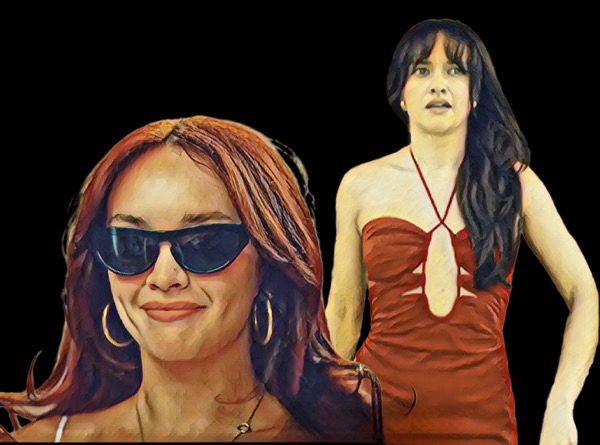

Watching Olivia Cooke in The Girlfriend — the thriller directed and starring Robin Wright that just premiered on Prime Video — reignited my frustration with House of the Dragon. I won’t spoil the new series (or at least not too much), but I have to admit: Cherry Laine made me imagine how much sharper, more dangerous, and more fascinating Alicent Hightower could have been.

Cherry is a richly layered character, and Olivia is simply phenomenal in the role. On page and screen, Cherry is complex and contradictory: the daughter of a bricklayer and a butcher, she is determined to fight her way out of a world stacked against her. When a promotion goes to someone more privileged, she “steals” a sales opportunity that ends up changing her life — and that’s how she meets millionaire Daniel Sanderson (Laurie Davidson), who will become her boyfriend and the focus of the psychological tension that drives the series.

What’s most fascinating, though, is how Cherry moves between vulnerability and menace. Her “white lies” quickly create a chasm between her and Daniel’s family, especially his mother, Laura, who senses that something about Cherry doesn’t quite add up. The series brilliantly plays with this ambiguity: at times we’re completely on Cherry’s side, understanding her motives, but then we realize she’s more dangerous than she first seemed — perhaps the only one really capable of turning the tables.

And that’s when my thoughts go to Alicent.

In Fire & Blood, Alicent is a formidable antagonist. Much older than Rhaenyra, she has the ambition and ruthlessness to become a decisive force in the civil war that nearly wiped out the Targaryens. Even as a pawn in the hands of more powerful men, she finds ways to manipulate, persuade, and make sure her children stay one step ahead. On the page, she is cunning and dangerous, which makes her clash with Rhaenyra electrifying.

In the series, however, the choice to de-age her and make her Rhaenyra’s childhood friend is dramatically compelling but also softens the character. In Season 1, we saw Alicent as a frustrated mother, living a life shaped by duty and expectation, only to watch Rhaenyra — who broke rules, found love and sexual freedom — still destined to be queen. This contrast is powerful. The show doesn’t lean into Alicent’s maternal instinct (which is bold and interesting) but instead into her envy of her former friend and stepdaughter’s freedom and life.

In Season 2, amid the first clashes of the war she helped ignite, Alicent begins navigating both her sexual awakening with Ser Criston Cole and an emotional distance from her children. After losing a grandchild, watching her firstborn become disfigured, and witnessing thousands die in the war for the crown, she goes as far as to strike a deal with Rhaenyra: hand over her sons in exchange for the chance to escape into exile with her daughter, Helaena. Book purists are furious about this change — because no matter how much the show bends the events, it can’t alter the inevitable, tragic ending of the Dance of the Dragons, making every effort feel futile.

The problem is that even with these bold choices, the show still avoids the Alicent who is as cunning and cruel as Cherry — the Alicent who could be capable of truly violent, shocking acts. Cherry’s emotional instability also drives her toward tragedy, but she remains an active, chaotic force. Alicent, on screen, feels more like a victim than a player. Imagining her with Cherry’s energy — willing to scheme, to manipulate, to act — would make House of the Dragon even more intense and riveting.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.