I’ve never been a fan of horror — not ever. The sounds of the Alien franchise, the gore, the acidic vomit, the body horror that has always been its trademark… all of it repels me. The Alien universe made me watch with half-closed eyes at the theater, ready to look away before the scare or the disgust hit. And yet, I surrendered to Alien: Earth. I didn’t just watch it all — I became fascinated.

Noah Hawley’s brilliance is undeniable. He managed to expand a mythology that once seemed sealed shut and turn it into an existential and political drama, something far beyond “hunt or be hunted.” Episode by episode, the series peeled back layers of what we knew as Alien. If the films drew power from silence and mystery, Hawley dared to give the xenomorphs context, voice, and even dramatic function. That choice divided fans from the start — and it’s not hard to see why. There’s something almost sacrilegious about trying to humanize (or “domesticate”) the monster. And yet, I surrendered to Alien: Earth. I didn’t just watch it all (except for the final two episodes, where I’m sitting with the audience): I found myself fascinated.

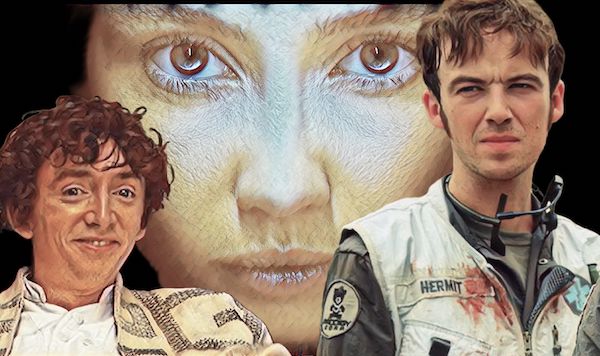

The penultimate episode of the season (Episode 7) is the definitive turning point. It was one thing to watch the show slowly reveal that Wendy (Sydney Chandler) was developing the ability to communicate with xenomorphs — a path that could’ve gone in many directions, especially with Boy Kavalier (Samuel Blenkin) acting as the cruel puppetmaster behind Wendy and her hybrid “siblings.” But it’s another thing entirely when, finally disillusioned with Prodigy’s manipulations, Wendy decides to release her “xeno-pet” from its cell — with a room full of employees still inside. What follows is pure Alien in its most visceral form: the xenomorph tears through scientists, technicians, and then a squad of Weyland-Yutani soldiers, ending the episode on a cliffhanger as brutal as it is symbolic. We’re no longer in Ridley Scott’s claustrophobic horror. This is open warfare, and the creature has become a weapon of rebellion. Wendy is no longer a victim. She is an agent — and her act is both liberation and condemnation.

This narrative turn is both powerful and controversial. It’s a complete reversal of the core dynamic of Alien. Since the 2000s, fans have been wary when new installments try to explain, trace, or psychologize the xenomorph. Part of the monster’s power lies in being unknowable. Seeing Wendy turn it into something between pet and weapon is disconcerting. But here’s the point: that’s Hawley’s very audacity. By giving Wendy that power, he sets up a complex moral debate. This isn’t just spectacle for spectacle’s sake. It’s a conscious choice by a character who is still, technically, a child. A young girl unleashing a killing machine on other humans — and framing it as justice. This is one of the most unsettling ideas the series has ever put forward, and it’s impossible not to react. But I’d argue it’s also where Alien: Earth becomes its boldest. One of the show’s posters, by the way, was rather spoilery.

Wendy’s transformation is the emotional heart of the season. Hawley has been building this turn since the first episode. The hybrids have always been the narrative center — and in that sense, the series is almost a fable about what we do to today’s children: we create hostile systems, destroy the planet, make them guinea pigs in our wars and social experiments, and then expect them to remain “normal.” Kirsh (Timothy Olyphant) has been the mentor figure, the prophet almost, urging the hybrids to reject their humanity and embrace something “greater.” Wendy had already demonstrated abilities far beyond expectation: remote control of machinery, hand-to-hand combat lethal enough to kill a xenomorph, and now full communication with them. Freeing the “pet” is the apex of her emancipation arc — but also the moment she steps away from what we recognize as human. That Wendy feels more kinship with a Prodigy-engineered alien than with the humans who betrayed her is a devastating commentary on belonging. She chooses the other, the strange, the unacceptable — and in doing so, renounces the human community that had already renounced her.

Boy Kavalier is a fascinating villain precisely because he is never a caricature. He isn’t just a “mad scientist,” but a man who wants to rewrite human nature itself — and control whatever comes next. There’s almost a religious subtext to Boy’s vision: he wants to be the god of the new world, and the hybrids are his creatures. The presence of Species 64 (the “sheep alien”) is part of this arc — the limit case, the creature we can’t tell if it’s a weapon, oracle, or abomination. Everything about it is discomforting, and it’s possible that in the finale, we’ll see Boy attempt to use it as the keystone in his twisted evolutionary design.

One of the great strengths of Alien: Earth is how it brings to the surface what was always in the franchise’s subtext: the politics of the body. Alien has always been about forced pregnancy, corporate exploitation, gendered violence, and cannibalistic capitalism. Hawley just made it explicit. Watching now, you can’t help but think of scientific ethics, biotech, AI, and bodies controlled by governments and corporations. And then there is the existential horror: Wendy may be humanity’s savior or its destroyer — and perhaps there is no difference between the two. The series forces us to ask if we even want to survive in a world that demands this kind of bargain.

When asked by GQ how he’d tee up the finale, Timothy Olyphant perfectly captured the feeling that episode 7 leaves behind: “When we shot that ending, I had one of my favorite feelings, which is that it felt totally unexpected, yet inevitable. Like, of course, this is where it was headed from the jump. I think it’s going to be both a very satisfying ending and have people really leaning forward. The idea of another season is a year-plus away, but, boy, that ending feels like, okay, let’s get to it!” And that is exactly where I am now: leaning forward, anxious, and nauseous. The show won’t let me rest. I know the finale will be punishing, but I also know I’ll watch. Because Alien: Earth has never been content to be just horror or just science fiction — it pokes, it hurts, it asks what it means to be human, and whether it’s even worth it anymore.

Will Wendy turn against her brother, whom she believes betrayed her? Who does Boy Kavalier see as the perfect vessel to implant the “eye” and interact with the intelligent alien species? My money is on him trying the experiment on Wendy herself — or, yes, on her brother. But wanting it is one thing: will he actually succeed?

The penultimate episode is more than a setup for the finale — it’s a declaration of war on our complacency. It asks what we’re willing to accept as just, as human, as moral. Wendy becomes judge, executioner, and liberator. And we, the viewers, become complicit. I came into this universe with half-closed eyes. Now I watch with eyes wide open — even if it costs me a sleepless, queasy night. Because that’s what great fiction does: it forces us to look at the monster. And sometimes, the monster is us.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.