There is something deliciously ironic — almost perverse — about the way Marie Antoinette is celebrated today. The queen who once embodied everything wrong with the Ancien Régime — excess, detachment, frivolity — who was humiliated, imprisoned and guillotined at just 37, is now adored as a fashion icon, a designer’s muse, and the centerpiece of a blockbuster exhibition at London’s V&A. What was once her greatest condemnation — her appetite for luxury and taste for parties — has become her redemption. History, it seems, has given her the ultimate makeover.

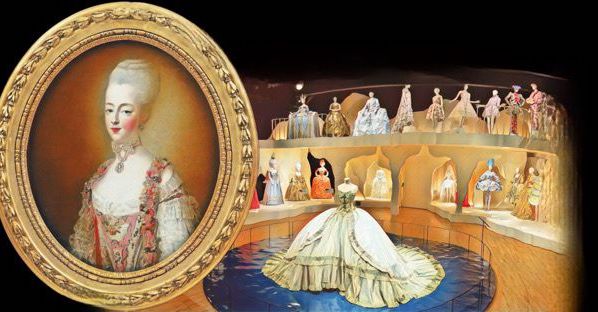

The newly opened Marie Antoinette Style exhibition at the V&A is the most recent chapter of this retelling. Bringing together 250 objects — original gowns, shoes (she famously ordered two pairs a week!), jewelry, portraits, and re-creations of her beloved Petit Trianon — the show places Marie Antoinette, as curator Sarah Grant puts it, “at the center of her own story.” There is even a guillotine on display, not as a grisly spectacle, but as a contextual reminder that the young woman behind the legend was consumed by the fury of her era. This is not the “let them eat cake” caricature of revolutionary propaganda but a complex figure: a teenager-turned-queen who used fashion as both a form of self-expression and, perhaps, quiet rebellion in a court that denied her political agency.

This sympathetic reinterpretation did not begin today. Since the 20th century, historians, novelists, and filmmakers have revisited her story with growing fascination. Stefan Zweig’s famous biography painted her as a sensitive, tragic figure, almost a martyr. Classic films humanized her further, but it was Sofia Coppola’s 2006 masterpiece that restored her to full pop-culture glory. Kirsten Dunst’s portrayal presented Versailles as a pastel dreamscape scored by indie rock, with macarons as props — a cinematic language that forever reframed our mental image of the queen.

And in many ways, Marie Antoinette earns the title of the most fashionable queen in history. With her dressmaker Rose Bertin and hairdresser Léonard Autié, she turned Versailles into a stage. She popularized the “robe à la reine,” a looser, more natural silhouette that scandalized the court, and made the sky-high pouf hairstyle a signature of the era. She was obsessed with everything English — fabrics, hats, pastoral trends — importing what she saw as the most modern aesthetic of the time. In a sense, she became the first global fashion influencer, with every court in Europe copying her look.

Comparisons with other royal women help to explain her enduring grip on the imagination. Elizabeth I used clothing as a political statement, projecting virgin majesty to legitimize her rule. Queen Victoria defined the aesthetics of grief and popularized the white wedding dress as a symbol of purity. In the 20th century, Princess Diana transformed fashion into a means of emotional communication and rebellion within the confines of the monarchy. But none had Marie Antoinette’s mix of youth, aesthetic daring, and tragic ending — a combination that forever froze her in the collective memory. The queen who was once reviled became, with time, the object of endless fascination.

And if we can admire these objects today, it is because some of them miraculously survived a time when everything they represented was meant to be erased. After the fall of the monarchy, much of what was at Versailles and Petit Trianon was looted, auctioned off, or destroyed. Some pieces were acquired by émigrés or foreign collectors who valued their historical significance. Others were stored in French state depots and rediscovered in the 19th century, when nostalgia for the monarchy resurfaced under Napoleon III. Today, scholars rely on court inventories, engraved monograms (“MA”), detailed provenance records, and even contemporary portraits by Vigée Le Brun to authenticate which objects truly belonged to the queen. This makes moments like the V&A show particularly moving — such as the reunion of her favorite jewelry box with pieces of her original jewelry, together for the first time since the 18th century. It is as though history has been pieced back together.

The V&A exhibition doesn’t stop at historical reconstruction; it shows her influence on modern design. Moschino’s cake-layer gowns from the 1990s, Vivienne Westwood’s bridal creations, and Alessandro Michele’s couture debut for Valentino are all displayed alongside Sofia Coppola’s film costumes. It’s a timeline stretching from the 18th century to the present-day runway, proving that Marie Antoinette is not just a historical figure but a muse who continues to inspire.

Perhaps what captivates us most is the contrast she embodies — youth and tragedy, beauty and downfall, luxury and vulnerability. Hers is a story of excess, yes, but also of fragility and humanity. By celebrating her as the most fashionable queen in history, we are not simply admiring her wardrobe; we are participating in a collective act of historical reimagining, one that allows glamour and tragedy to coexist. Between the Petit Trianon and the Place de la Révolution, Marie Antoinette continues to remind us that fashion may be frivolous — but it is never innocent.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu