In The Age of Innocence, May Welland is the most refined — and therefore the most unsettling — portrait of what Edith Wharton calls “good breeding” in late nineteenth-century New York: a web of gestures, silences, and conventions that, under the guise of purity, quietly governs destinies. She is both a hothouse flower and a gardener.

Raised to embody the ideal of the “well-born girl,” she personifies the whiteness her society worships — translucent skin, discretion worn like a jewel, lily-of-the-valley as her signature scent — and she learns, with devastating naturalness, to turn this ideal into a tool. She is not just the spring bride her name suggests; she is the guardian of the seasons. When Newland Archer dreams of freedom with Ellen Olenska, it is May who understands — before he does — that freedom in this world is conjugated in private and denied in public. The entire novel is a choreography of this realization: on one side, “innocence” as a founding myth; on the other, the social intelligence that ensures that myth never collapses.

But beyond this social surface, the question remains: what does May feel? And it is here that Edith Wharton opens the most intimate layer of her character.

Did May love Newland?

Yes, she did — but in the emotional vocabulary she had been taught. May’s love is not feverish like Newland’s for Ellen, nor transgressive; it is a love that blends with loyalty to the shared life project they represent together. She wants to be the perfect wife and mother, and she wants Newland to inhabit his role as perfect husband with equal precision. Hers is a love that longs for stability, not combustion. When May shortens the engagement, when she tries to please and fulfill every expectation, it is not merely a strategy — it is a genuine desire to achieve that ideal of “conjugal happiness.”

Wharton suggests that May, in her own way, suffers from Newland’s restlessness. But she does not choose the path of confrontation. Her way of loving is to keep everything on course — even if that means acting silently to neutralize threats to what she has built. In other words, she does love him, but her love is inseparable from preserving the system.

Did she lie to Ellen about the pregnancy?

This is one of the most debated — and brilliant — passages in the book. When May tells Ellen she has “just found out” she is pregnant, Wharton never confirms for the reader whether this is true at that exact moment or whether May is announcing something that has not yet been confirmed. Wharton’s word choice — and the fact that the scene is told from Newland’s perspective — creates a deliberate haze.

What we do know is that the gesture has an immediate effect: Ellen decides to leave. In other words, May’s intention is clear — to remove the rival in a way that no one can criticize. One can read this as a “strategic lie,” but it can also be read as a masterful use of a potential truth (since she does become pregnant shortly thereafter). What matters to Wharton is not the clinical accuracy of the announcement, but the social calculation behind it: May knows that the mere idea of a pregnancy is enough to make an affair unthinkable.

What does this say about May?

This scene is the apex of her social intelligence. For some readers, it is proof of manipulation; for others, a desperate act to save her marriage. Both readings are legitimate. The crucial point is that Wharton does not reduce her to a “villain” — she shows us how May uses the weapons available to her: her position, her reputation, and the weight of the future child.

At its core, this is indeed a gesture of love — but a love that expresses itself through control. May does not want to destroy Newland; she wants to keep him within the pact they made. If Ellen represents the possibility of rupture, May represents the world that has chosen to keep existing. It is precisely because she acts as silently as she does that the metaphor of May as Diana, the archer, becomes so powerful.

In the countryside, bow in hand, she embodies an ideal of contained energy, perfect aim, effortless grace. The metaphor is transparent: in a universe where everyone reclines on embroidered sofas, the one who holds the bow controls the distance — and the narrative. May’s arrow is anticipation: she is always a second ahead, with the exact smile, the perfect phrase, the date already set. Newland sees her as a “blank page” on which he could write his story, but blank pages, in Wharton, are treated surfaces: they repel unwanted ink. May’s whiteness is not emptiness; it is finish.

Newland’s great mistake is to confuse silence with the void. He projects onto his wife the fantasy of not-knowing: “if she knew, she would suffer; as she does not know, she is happy.” Wharton dismantles this illusion in the epilogue, when the adult son reveals that May always knew — or more precisely, always intuited — what her husband only dared to desire in thought. May’s final gesture, on her deathbed, carries the typical ambivalence of women of her class: a kind of inverted blessing. She trusts that she was “protected” by a man who gave up what he most wanted, and at the same time, she seals Newland’s narrative once and for all. Is it an act of love? Possession? Tribal loyalty? It is all of these at once. Wharton’s brilliance lies in leaving us inside this contradiction without resolving it.

Compared to Ellen, with her foreign color, her porous morals, and her refusal to pretend, May is the American standard brought to its highest polish. Ellen represents the irregular ventilation of the world; May, the smooth stability of the drawing room. It is no accident that the flowers surrounding each echo these qualities: for May, the compact, almost scentless white of a bridal bloom; for Ellen, richer colors and shapes, a fragrance that fills the room. Newland, who believes he prefers the wilder garden, spends his life inside the greenhouse, convinced that staying is a heroic sacrifice. The irony — and Wharton lives on delicate ironies — is that the person who truly acts, who truly decides everyone’s fate, is the one in whom the novel invests less color and more geometry.

That geometry is not cold. May has an ethic — only one that runs perpendicular to desire. Within her horizon, she cares: for her parents, her husband, their reputation, continuity itself. To do so, she accepts tradition as her axis and represses the unpredictable. This is why May’s power plays out in the register of the “as if”: as if she did not know, as if it did not hurt, as if the conjugal fabric had no seams. The cost of this performance is what makes the book tragic: May is not happy in the romantic sense; she is effective. And in the accounting of that society, effectiveness and happiness are almost indistinguishable.

The novel suggests that women find, in the interstices of protocol, micro-passages of power. Wharton maps these passages like a floor plan: the luncheon with the cousins, the note sent at the right moment, the visit that happens (or does not happen), the announcement made first to those who matter socially, not emotionally. May master the calendar the way others master capital. Her supposed passivity is a female version of “deal-making”: the art of obtaining the desired result without leaving evidence of the crime. If society is the courtroom, May is its prosecutor and liturgist — and, discreetly, also its beneficiary.

In literary terms, she fulfills a rare structural function: antagonist without malice, driver of conflict without flamboyance. In May, Wharton lays bare the machinery of custom: power that does not flaunt itself, violence delivered through gentleness, censorship spoken as counsel. When the narrative, decades later, offers Newland the chance to go upstairs and see Ellen once more, the fact that he remains on the street, looking at the closed window, seals not just the fate of a man but the triumph of a social aesthetic. This man was trained to love what he cannot touch. And the one who ensured that his training would not be defeated by impulse was the woman who seemed, all along, not to be playing.

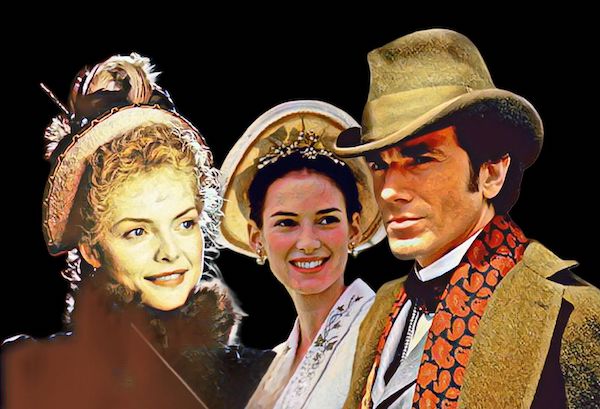

On screen, this dual layer of May — glittering surface, strategic intelligence — is often read in strikingly different ways. Winona Ryder, in Scorsese’s adaptation, plays her as porcelain with edges: there is sweetness, but also the sharpness of someone who measures the room as she enters it. This ambiguity is crucial to prevent May from being reduced to either the “wronged wife” or the “angel in the house.” Wharton’s interest lies precisely in showing that the angel in the house is, by definition, the most efficient strategist in it. In film or stage adaptations, when the actress finds the point where the smile both illuminates and delineates at the same time, we grasp the character’s reach: the glow is light and fence at once.

Reading May today through contemporary terms like “gaslighting” or “manipulation” risks losing half of Wharton’s precision, leaving us with only the comfort of moral judgment. What is in May is not malice; it is adherence. And that adherence is, in its own way, a form of virtue within the code in force. This does not absolve her — but it humanizes her. She chooses what she was trained to choose, and in choosing, she preserves the order that preserves her. Ellen pays the price of fresh air; May, the price of stability. There are no winners here, only a city that keeps running, polished, thanks to the invisible hands of women like her.

In the end, May Welland is the key to Wharton’s title. The “age of innocence” was not a time when people were pure; it was the time when purity was the most efficient name for a politics of manners. May is the high priestess of that cult: she offers white flowers, speaks impeccable words, and keeps everything in its place. Her triumph is silent, like most of the triumphs that truly matter for the maintenance of a world. Her failure, if we can call it that, is that to uphold this order she must renounce romance as experience — and force her husband to renounce it with her. Between passion and decorum, May chooses decorum. Between gesture and rule, she chooses the rule. Between being a person and being a function, she learns to be both. And it is precisely in this intangible equilibrium that her greatness — and Wharton’s critique — are revealed.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.