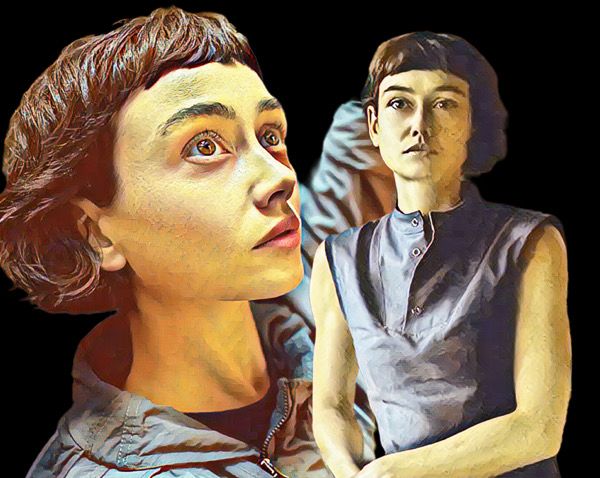

From the moment Alien: Earth was announced, there was an irresistible promise: we were finally getting a new Ripley. Marketing leaned into it hard — every interview, teaser, and poster suggested Wendy was destined to carry the torch as the next great female sci-fi protagonist. The comparison to Sigourney Weaver was not subtle — it was the pitch. But eight episodes in, the feeling is different: Wendy didn’t become the Ripley they wanted. And maybe she never will.

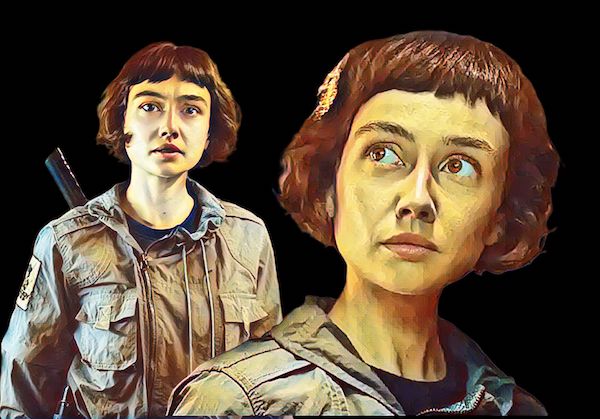

This is fascinating because Alien has always been about humanity under extreme pressure, and Ripley worked precisely because she was an ordinary person thrown into extraordinary circumstances. Wendy, on the other hand, enters the series already “special.” She communicates with xenomorphs, she has insights no one else has, and she is framed as the only one who can save everyone. But instead of rooting for her, audiences are keeping their distance. One of the most talked-about pieces this week labeled Wendy a “Mary Sue” — that trope of a character so perfect, so overly competent, that she feels artificial. And honestly? I kind of agree.

It’s not that Wendy is badly written. She has motivation, she has an arc, she delivers clever dialogue. But what she lacks is what Ripley had in abundance: vulnerability. When every other character feels flawed, fragile, painfully human — Joe, Shmuel, Boy Kavalier — Wendy should be our anchor of hope. But the empathy never clicks. We end up liking everyone… except her. And that’s a problem for a supposed lead.

Another layer here is the actress behind Wendy. Sydney Chandler isn’t exactly an outsider — she’s the daughter of a well-known Hollywood couple, carrying the unavoidable “nepo baby” tag. To make matters worse, the week of the premiere, she landed a Variety cover profile that tried hard to dismantle that narrative — and ended up sounding defensive, even a little tone-deaf. The timing was brutal: instead of drumming up curiosity, it created a backlash among viewers already skeptical of her.

But maybe this uneasiness is the whole point. Noah Hawley isn’t known for creating easy protagonists. Just look at Fargo: he loves morally complicated characters who take time to earn our affection. Wendy may just be one of those cases — a character we are meant to resist until she truly breaks. Maybe we need to see her lose, bleed, and make mistakes before she feels like one of us.

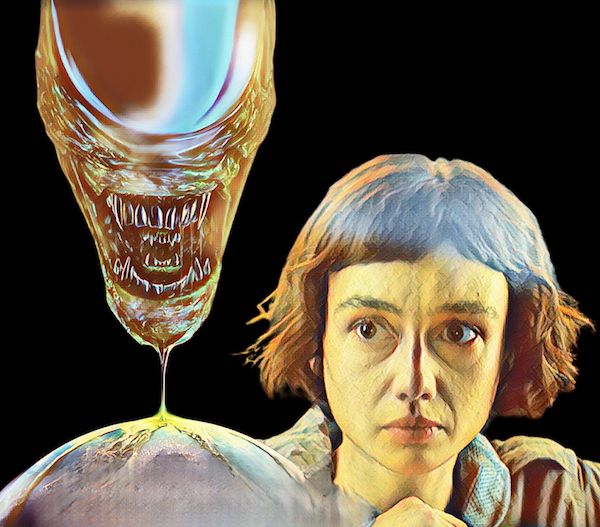

The “Mary Sue” label, after all, is loaded. It’s been weaponized to dismiss female characters for decades — from Rey in Star Wars (a textbook Mary Sue) or even Katniss in The Hunger Games (whom Jennifer Lawrence managed to balance with great skill). But Wendy’s reception feels more complex than garden-variety misogyny. It stems from the sense that she walked into the narrative with all the cards stacked in her favor. Ripley was an unlikely survivor. Wendy feels handpicked by the script to be the savior. That distance is what makes her hard to love.

Still, maybe the real mistake is expecting Wendy to be Ripley at all. Ripley was lightning in a bottle: a gender-neutral role that Sigourney Weaver transformed into an icon with sheer force of presence. Wendy doesn’t have to repeat that. Maybe she’s here to subvert the “final girl” archetype, to challenge our need for an instantly relatable hero. Maybe our frustration is exactly what the writers want.

If that’s the case, it’s a brilliant narrative trick. By making us prefer the supporting characters, the show puts us in a place where we want Wendy to prove she deserves the lead role. We want her to stumble, to be humbled, not out of cruelty but so we can finally root for her comeback. And if that happens, years from now, we may well be calling her Ripley’s rightful heir. For now, Wendy remains a hard-to-love heroine — and that might just be the entire point.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.