Prophecies have always haunted humanity. In history, they were used as political weapons. Egyptian pharaohs interpreted dreams as divine mandates. At Delphi, priestesses spoke in riddles that sent armies to war. Alexander the Great never marched without consulting an oracle. Medieval kings crowned themselves as God’s chosen. And Nostradamus became immortal by writing verses vague enough to “predict” every catastrophe that came after.

Psychology gave a name to this phenomenon: the self-fulfilling prophecy. When we believe something strongly enough, we act in ways that make it happen. The destiny wasn’t inevitable—it was manufactured by belief itself.

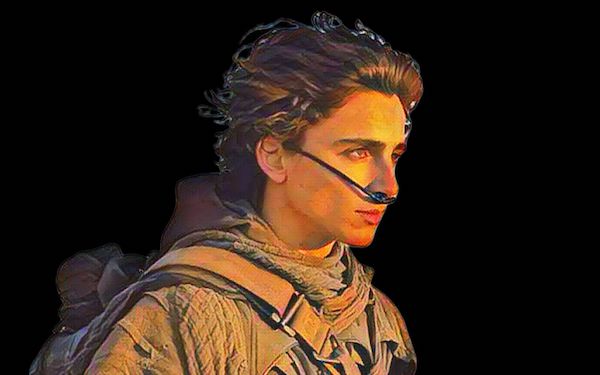

Fiction couldn’t resist. Shakespeare built Macbeth entirely on the misreading of prophecy. The witches never lied—Macbeth interpreted wrongly, and his downfall came from believing too much. Tolkien gave Aragorn the burden of fulfilling his lineage’s promise, a prophecy resolved with reassurance. J.K. Rowling crafted a prophecy that could apply to Harry or Neville, but it was Voldemort’s obsession that made it real. Frank Herbert, in Dune, was far more brutal: prophecy was no divine revelation, but a Bene Gesserit program to manipulate populations into obedience.

And George R. R. Martin? He plays the cruelest game. In A Song of Ice and Fire, prophecies don’t reveal the future—they reveal character flaws. His players interpret fragments, chase shadows, and destroy themselves. As Martin once said: “Prophecies are meant to fool characters, not readers.”

The Red Comet: Everyone Sees What They Want

One of Martin’s most brilliant tricks is the red comet that streaks across the sky in A Clash of Kings. Every character reads it differently. Melisandre sees Stannis’s divine confirmation. Daenerys’s followers see a sign for the “Mother of Dragons.” Maesters argue it’s nothing more than astronomy. The same symbol fuels contradictory destinies.

This is pure Martin: the sign is neutral, the meaning comes from interpretation. It is a Jungian archetype in motion—the symbol exists, but its power comes from projection.

Daenerys: The Vision No One Wanted to Believe

No character embodies the danger of prophecy more than Daenerys Targaryen. Fans still reject her ending in Game of Thrones, but her fate had been laid out years earlier. In the House of the Undying, Daenerys sees the Iron Throne destroyed, covered in snow (or ash). She reaches for it, but a noise from beyond the Wall pulls her away. She then reunites with Drogo and her dead child.

The vision was clear: she would burn King’s Landing to the ground, never sit on the throne, and her “victory” would be death. The audience simply didn’t want to read it that way.

Daenerys followed the arc of a classical heroine—abused, resilient, compassionate, liberator of the oppressed. But alongside justice grew her narcissism and her myth-making. Tyrion warned us: “Everywhere she goes, evil men die, and we cheer for her. But she grows more certain she is good and right.” Applause became fuel. Belief became blindness.

When the twist came—Daenerys torching King’s Landing even after victory—viewers cried “betrayal.” But in Martin’s logic, it was the inevitable end of her self-created legend.

The ripple of this choice still affects House of the Dragon. Every Targaryen woman onscreen is now shaded by Daenerys’s legacy. Rhaenyra, in the show, is patient, just, almost too diplomatic. But in Fire & Blood, she is paranoid, wounded, proud, and capable of embracing violence as “justice.” Onscreen, her rough edges are sanded down. Helaena, too, is softened into allegory instead of visceral tragedy. This is what I call the “Daenerys Syndrome”: all Targaryen women are forced into her mold, simplified for fans who want the queen they imagined, not the messy figures Martin wrote.

Jon Snow: The Heir Who Refused the Legend

Jon Snow is the opposite case. Identified by Melisandre as the Prince That Was Promised, Azor Ahai reborn, Jon never cared. He fought because it was his duty, not because prophecy told him to.

Rhaegar, Jon’s true father, embodied the opposite. Obsessed with the “Song of Ice and Fire,” he named not one but two sons Aegon, hoping to fulfill destiny. He abandoned Elia Martell. He destroyed his marriage. He triggered Robert’s Rebellion. In the end, Jon—Aegon VI—was indeed the rightful heir. And Martin’s cruel irony: the true heir never wanted the throne.

Macbeth, Dune, and Westeros: Different Destinies

The parallels are striking. Macbeth hears he will be king. He forces the outcome and is ruined. Dune presents Paul as the messiah, but later reveals the prophecy was engineered—a cage disguised as faith. Westeros merges both: prophecies are ambiguous like the witches and manipulative like the Bene Gesserit. But with one twist: no one ever has the full picture. Each character believes in fragments, and all stumble into tragedy.

The Curse of the Aegons

Rhaenyra and Daenerys share another curse: both lost their crowns to an Aegon. Rhaenyra was usurped by Aegon II. Daenerys lost to Aegon VI—Jon Snow. Neither woman was toppled by her own failure alone, but by men whose only “virtue” was birthright. A pattern runs through Targaryen history: Aegons always rise, and women always bleed for it.

Prophecy as Political Excuse

House of the Dragon added another layer: Aegon the Conqueror supposedly had a vision of a coming winter and the need for a united Westeros. He called it A Song of Ice and Fire. It reframes conquest as destiny. But let’s be honest: Aegon did not invade for prophecy—he invaded for power. The vision retrofits politics into “divine mission.”

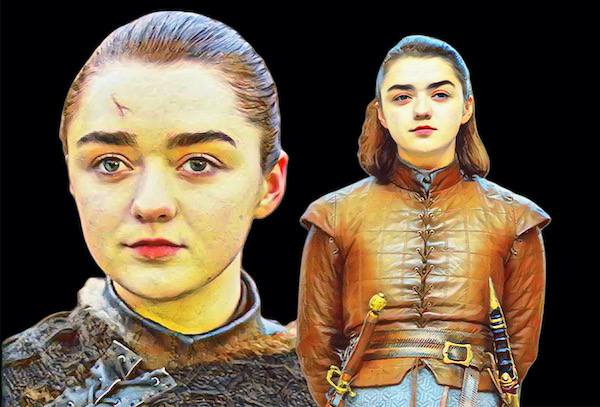

And yet this whisper of destiny shapes everything after. Viserys obsesses over it. Alicent misunderstands it. Rhaenyra inherits it as a burden. All for nothing. Because in the end, who killed the Night King? Arya Stark. A woman with no prophecy, no dragon, no destiny. Just a choice.

Fan Theories: Who Was Azor Ahai?

Fandom has filled the vacuum Martin left. Jon is the perfect balance of ice and fire. Daenerys is Lightbringer incarnate with her dragons. Arya is the practical fulfillment. Bran is the true catalyst. Jaime, as the most elegant twist—his journey matches the three failed attempts to forge Lightbringer, and killing Cersei could have satisfied the Valonqar prophecy too.

The point is: Martin built space for every theory. And by withholding The Winds of Winter, he forces us to live in the uncertainty his characters feel.

The Stark Women and the Price of Prophecy

Lyanna Stark is another example of prophecy’s collateral damage. Rhaegar’s obsession with “the dragon has three heads” led him to her, and their union sparked the rebellion that ended a dynasty. Elia Martell died because of it. Lyanna died in childbirth because of it. And Daenerys was born in exile because of it.

Across time, women—Rhaenyra, Lyanna, Daenerys—pay the blood price for men’s prophetic obsessions.

Prophecy vs. Choice

That is the final lesson. In Martin, prophecy never dictates the future—it dictates mistakes. Daenerys burned because she believed too much. Jon survived because he ignored it. Rhaegar shattered his family in pursuit of it. Viserys doomed his house through misunderstanding. Arya, who carried no prophecy, saved the world.

In The Lord of the Rings, prophecy reassures. In Harry Potter, the ambiguity is intentional, yet it fulfills the messianic arc. In Dune, it is manipulation. In Westeros, it is noise. A crooked mirror.

And maybe the greatest prophecy of all is the one haunting us readers: that George R. R. Martin will one day publish The Winds of Winter. For over fifteen years, we’ve waited. Perhaps it will bring answers. Perhaps it will bring more confusion. Maybe it will only be another red comet: a sign we read differently, each according to our hopes.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

2 comentários Adicione o seu