Some crimes fade. Others multiply.

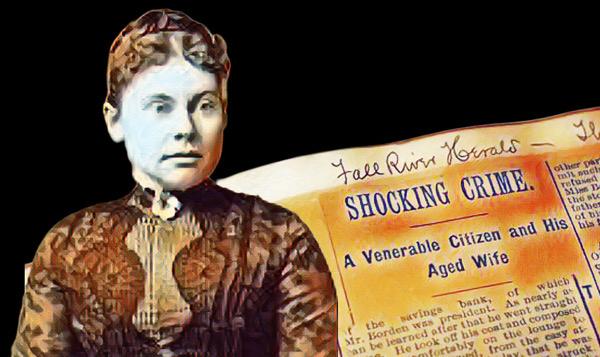

The name Lizzie Borden has survived for more than 130 years — not merely as a criminal case, but as a myth.

Since 1892, when her father and stepmother were brutally murdered with an axe inside their family home in Fall River, Massachusetts, Lizzie has occupied a singular space in American culture: that of the woman who may have committed the perfect crime — or the woman who carried forever the burden of one she did not commit.

Her story became a children’s rhyme, a stage play, an opera, a series of films, television dramas, musicals — and even a ballet.

Since the early twentieth century, Hollywood has returned to Lizzie again and again, in cycles of fascination and horror, and each actress who portrayed her revealed a different facet of the same mystery.

Lizzie Borden on Screen — The Many Faces of the Same Myth

The first major reinterpretation for the screen came in 1975, with Elizabeth Montgomery in the television film The Legend of Lizzie Borden. It was a daring choice: Montgomery, America’s beloved witch from Bewitched, suddenly embodied a cold, lucid, and eerily self-possessed murder suspect. Directed by Paul Wendkos, the production earned four Emmy nominations and entered pop culture history for its audacious implication — that Lizzie might have committed the murders in the nude, a visual metaphor for both liberation and shame.

That same year, Hope Lang starred in The Mystery of Lizzie Borden, a more analytical, almost documentary-style version. By the 1980s, Lynda Carter, the iconic Wonder Woman, appeared as narrator in a series of televised crime reenactments, further cementing Lizzie’s place in pop mythology.

Decades later, the myth was reborn. In 2014, Christina Ricci reimagined Lizzie with irony and defiance in Lizzie Borden Took an Ax, a Lifetime Channel production. The film’s success spawned a sequel miniseries, The Lizzie Borden Chronicles (2015) — a gothic, semi-supernatural continuation that turned Ricci’s Lizzie into a charismatic anti-heroine. Her version of the character was cynical, magnetic, and fully aware of how fear can become power. It was a feminist reinvention of the legend — a Lizzie who refused to apologize.

In 2018, the story received its most intimate and political treatment with Lizzie, directed by Craig William Macneill and starring Chloë Sevigny opposite Kristen Stewart as Bridget Sullivan, the family maid. This was the first portrayal to center female oppression as motive — presenting Lizzie as a woman imprisoned by patriarchy and paternal abuse, who finds in violence her radical escape. The queer subtext that hovered in earlier versions became explicit. The film is quiet rage turned into action.

On stage, Michelle Fairley (Catelyn Stark in Game of Thrones) embodied Lizzie as a symbol of Victorian hypocrisy in a 2008 Edinburgh Festival production.

And in 1965, composer Jack Beeson premiered his opera Lizzie Borden at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, transforming the case into a modern tragedy. There, Lizzie was not a criminal but a victim of repression, crushed by social and familial convention.

In the 2010s, the myth even roared back in punk-rock form with Lizzie: The Musical (2010), created by Steven Cheslik-deMeyer, Alan Stevens Hewitt, and Tim Maner. The show features four actresses representing different sides of Lizzie — the daughter, the victim, the lover, the killer — and in one version, Amanda Palmer wielded the axe like a symbol of feminine fury, not guilt.

And in dance, her story took flight — literally.

When Lizzie Became Music and Movement

One of the most striking artistic interpretations came not from cinema but from ballet. In 1948, choreographer Agnes de Mille created Fall River Legend for the American Ballet Theatre, set to an original score by Morton Gould.

De Mille, famed for Rodeo and Oklahoma!, reimagined the Borden case as a Puritan ghost story. The ballet’s protagonist, known only as The Accused, never explicitly kills anyone — but every gesture trembles with repression, fear, and guilt. The spare, austere staging, the harsh religious imagery, and Gould’s ominous score turned Lizzie’s tragedy into a psychological dance drama about fate and hysteria.

Fall River Legend remains one of the great American ballets of the twentieth century — not for depicting the crime itself, but for expressing what no trial ever could: the suffocating silence of a woman crushed between innocence and sin.

Since then, Lizzie’s myth has inspired modern dance solos, feminist performance pieces, and even contemporary works about domestic violence — each a new echo of that same impossible question: what happens when a woman refuses to remain small?

The Hollywood Heiress Who Becomes the Myth

Curiously, the new Lizzie Borden emerges from a different kind of American legend: Hollywood itself. Ella Beatty, who will play Lizzie in Ryan Murphy’s upcoming season of Monster, is the daughter of Annette Bening and Warren Beatty — two icons who represent entirely different eras of cinema.

A graduate of the Juilliard School, Ella belongs to a generation of performers who combine lineage with introspection. Before taking on the role of Lizzie, she appeared in Murphy’s Feud: Capote vs. The Swans (2024) and drew attention for her quiet intensity and ambiguous gaze — qualities that now feel tailor-made for Lizzie, a woman forever observed and rarely understood.

It’s no coincidence that Murphy chose a Hollywood heiress to portray the woman America could never decode. Raised in the shadow of fame and legacy, Ella now inherits a different kind of burden: embodying the public’s obsession with women who dare to defy the roles assigned to them.

Ryan Murphy and His Fascination with Real Monsters

After transforming Dahmer, the Menendez brothers, and Ed Gein into reflections of morality and voyeurism, Ryan Murphy has found his perfect bridge between horror and social critique in Lizzie Borden.

The upcoming fourth season of Monster — now in production — boasts an extraordinary cast: Ella Beatty as Lizzie; Rebecca Hall as Abby Borden, the stepmother; Vicky Krieps as Bridget Sullivan; Billie Lourd as Emma, the sister; and Jessica Barden as Nance O’Neill, the actress and rumored lover. Directed by Max Winkler, the season promises Murphy’s signature balance of historical reconstruction and psychological delirium — where the axe becomes metaphor, and the true horror lies in the moral hysteria that turned a woman into a monster.

A Life That Seemed Ordinary

Lizzie was born in 1860, the daughter of Andrew Jackson Borden, a severe, self-made businessman. Her mother died when Lizzie was a child, and her father soon remarried Abby Durfee Gray, a woman the daughters never fully accepted.

Though wealthy, Andrew kept the family in modest, almost austere conditions. Lizzie was devout, respectable, and active in her church — the image of virtue. But behind closed doors, the Borden home was cold, silent, and full of locked doors.

Rumors swirled about inheritance disputes, simmering resentment, and emotional distance. What looked like discipline from the outside felt, on the inside, like suffocation.

The Morning Horror Came to Fall River

On August 4, 1892, the routine of Fall River was shattered. Abby Borden was killed first — 19 blows from an axe in a guest bedroom. Hours later, Andrew was found on the sofa, his face destroyed by ten more strikes.

The house was locked from the inside. The maid, Bridget Sullivan, testified that Lizzie had called for help. There was no sign of forced entry.

Suspicion turned inward.

Lizzie’s composure struck investigators as unsettling. Her statements changed slightly each time. Within days, the beloved Sunday school teacher had become America’s most infamous suspect.

The Trial of the Century — and the Birth of a Legend

In 1893, Lizzie Borden stood trial. Newspapers across the country turned it into a spectacle. For the first time, America confronted an image both fascinating and horrifying: a “proper lady” accused of patricide.

The jury — twelve men — could not bring themselves to convict her. They acquitted Lizzie, but absolution in court did not mean forgiveness in life.

She and her sister moved to a new house, Maplecroft, where they lived quietly but never escaped scrutiny. Fall River shunned them. Lizzie lived, and died, under the weight of silence. She passed away in 1927, at sixty-six, and was buried beside her father and stepmother.

Between the Axe and the Myth

The Borden case endures because it crystallizes the core of true crime: the abyss between appearances and truth.

Motives remain speculative — money, rage, resentment, and sexual repression. The rumored affair between Lizzie and Bridget Sullivan has gained traction in recent decades, and under Murphy’s lens, it will likely take center stage.

But the story ultimately speaks to control — the control of women, of sexuality, of narrative. Lizzie was judged not only for the crime but for being unmarried, independent, and unreadable. For daring to exist outside expectation.

The Fascination That Never Dies

More than 130 years later, Lizzie Borden still watches us — from films, stages, operas, and ballets.

There is no confession, no closure, no truth — only the echo of a question that refuses to fade:

Who truly held the axe — and who placed it in her hands?

Monster: The Lizzie Borden Story doesn’t need to answer “who killed them.”

Its power lies in asking what the case says about us — about our endless hunger for guilt, blood, and redemption.

Ryan Murphy has always understood that his monsters are mirrors. Lizzie, like all of them, reflects the world that made her. And when she looks back at us, her stare still asks the only question that matters: Who is the real monster in this story?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.