Ryan Murphy’s talent is undeniable. Few creators in contemporary television move so effortlessly across genres — from the pop melodrama of Glee to the political intrigue of The Politician, from the stylized terror of American Horror Story to the dark realism of Dahmer. And yet, his visual and narrative signature remains instantly recognizable: a fascination with the aesthetics of discomfort and an irresistible urge to provoke.

After being heavily criticized for “exploiting” personal and collective trauma in his retelling of true crimes, Murphy doubles down with Monster: The Ed Gein Story, the third installment in the anthology franchise that became one of Netflix’s biggest hits. If The Jeffrey Dahmer Story and The Menendez Brothers already unsettled audiences with their approach to tragedy, this new season goes further — darker, denser, and, paradoxically, more self-aware.

The Mirror of Horror: When the Audience Is the Real Monster

Murphy has never been a subtle storyteller, and here his intention is crystal clear: to confront the society that consumes true crime as entertainment. In revisiting the case of Ed Gein — the Wisconsin farmer who inspired Norman Bates (Psycho), Buffalo Bill (The Silence of the Lambs), and Leatherface (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) — the creator seems less interested in the killer himself and more obsessed with the viewers.

There’s plenty of blood and meticulous recreations of scenes that Hollywood turned into myth, but Murphy’s real point lies elsewhere: the horror is in the audience. Monster turns against the very genre it belongs to, questioning how far society has gone in normalizing violence and aestheticizing other people’s pain. It’s a powerful commentary — though one repeated so often that it becomes, ironically, didactic.

Between Reality and Artifice

This story could have been told in four episodes, yet it drags on for over eight, losing focus in the process. Throughout the season, the script blends fact and fiction — sometimes creatively, sometimes conveniently. Ed Gein officially killed two people (possibly three), but the series amplifies the symbolic reach of his madness.

Only in the seventh episode does it explore Gein’s mental state in depth, revealing a diagnosis of schizoid disorder, which today would fall within the spectrum of schizophrenia. It’s one of the few moments when the show truly tries to understand, rather than simply depict, Gein’s mind.

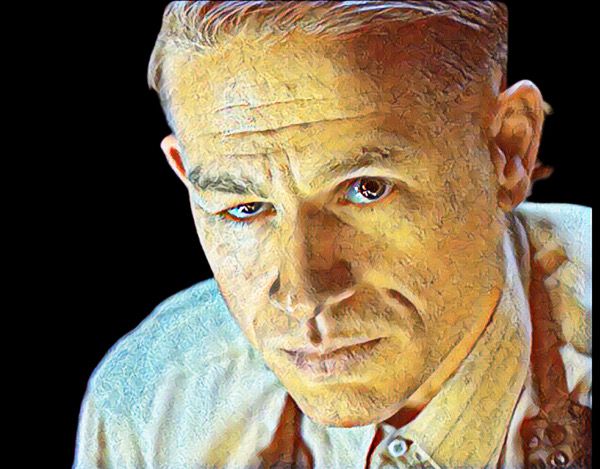

Charlie Hunnam delivers a remarkable performance — restrained, unsettling, and layered — one that could easily lead to awards recognition. Still, what could have been a psychological study is diluted by Murphy’s need to overexplain. There’s sincerity in his intentions, but very little mystery left for the viewer.

When Fiction Rewrites the Myth of Hitchcock

One of the most fascinating elements of the Gein case was its impact on popular culture. Writer Robert Bloch, who lived near Plainfield, drew direct inspiration from the case to write Psycho (1959), the novel that became Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece.

The series, however, only skims the surface of this connection between reality and fiction. Murphy doesn’t explore Bloch’s creative process or the complex relationship between trauma and art. Nor does he get all the historical details right: Anthony Perkins never hesitated to accept the role of Norman Bates — though he lived under the pressure of hiding his sexuality — and Hitchcock didn’t “end his career” after Psycho; he reinvented it, establishing the grammar of psychological horror. The film wasn’t just a stylistic breakthrough — it was also a veiled social critique.

A Nod to “Mindhunter” — and a Farewell to the Genre?

The final episode delivers an unexpected tribute to the brilliant (and prematurely canceled) Mindhunter, also on Netflix. It’s a knowing wink to true crime devotees and students of criminal psychology alike: the FBI agents who coined the term serial killer appear briefly, recalling their interviews with Gein — a real-life connection that Murphy turns into a metaphor for the birth of modern fascination with murderers.

From there, a procession of infamous names crosses the screen — Ted Bundy, Ed Kemper, and Richard Speck (who, in real life, did exchange letters with Gein), among others. They are portrayed as “fans” of Gein, even as the man himself, now cooperating with the FBI and his doctors, grows disillusioned, realizing that their promises to help him “get better” were never sincere.

This homage also feels like a farewell. Monster: The Ed Gein Story may be Murphy’s attempt to close a thematic cycle — to show that the real horror isn’t in Plainfield, but in the living room, among us, the viewers who turn monsters into cultural icons.

Between the Sacred and the Profane: The Legacy of American Horror

By positioning the Gein case as the origin point of the modern serial killer, the series revisits the DNA of an entire genre. Decades before Dahmer, Bundy, or Gacy, there were figures like Jack the Ripper and H. H. Holmes, whose “murder castle” was immortalized in the best-seller The Devil in the White City (still a passion project for Leonardo DiCaprio).

Murphy knows this lineage well and transforms Monster into a parable about America and its obsession with violence. At its core, the series exposes the culture of consuming barbarity — the endless cycle that runs from real crime to headline, from book to film, from trauma to streaming.

And it’s here that Ryan Murphy’s genius and his greatest vice converge: he denounces a system of which he himself is an essential part.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.