Few series have managed to fly so far under the radar while maintaining such creative consistency as Billy the Kid, from MGM+. Created by Michael Hirst — the mind behind The Tudors and Vikings — the show began as a modest promise: to revisit the legend of America’s most famous outlaw. But what Hirst built was something far greater. He turned myth into reflection, gunfire into silence, and the outlaw into a mirror.

Now, on the eve of its final season, Billy the Kid arrives at its last frontier with an unambiguous title: The Beginning of the End.

The Outlaw’s Final Act

At the start of Season 3, Billy remains a fugitive, still free after his spectacular escape at the end of the previous season. Hiding with Dulcinea in Saint Patricio, New Mexico, he plots revenge against the powerful men of The House, the political machine that rules the region with ruthless efficiency. Yet from the very first episode, there’s a lingering sense of finality — the air thick with the knowledge that his luck is running out.

Billy moves through this new chapter like a man who’s already glimpsed his own ending. Surrounded by enemies, he carries the weary composure of those who have lived too much, too fast. He even begins to resemble those detectives in crime dramas who are “one day from retirement” — the kind who fiction inevitably marks for death. When Dulcinea reveals she’s pregnant, that tension crystallizes. In television, having something greater than oneself to protect often seals one’s fate — and Billy’s is already written in blood.

Love, Death, and the Weight of Violence

The premiere sets a clear tone: personal tragedy mirrors the collapse of a nation. Billy and Dulcinea’s doomed love becomes the heart of the story — tender yet shadowed by inevitability. But tragedy doesn’t spare others. In one shocking subplot, Jesse stages a prison riot just to steal a moment with his lover, Ana. Their secret reunion ends in horror when Ana’s father bursts in, shoots at Jesse, misses, and kills his own daughter. Jesse retaliates, killing the man in return.

It’s a sequence that encapsulates the show’s moral complexity — violent, absurd, and painfully human. Like Billy’s own journey, it’s about the impossibility of love in a world ruled by cruelty.

Corruption and the Machinery of Power

While Billy hides in the desert, politics brew in the corridors of power. Catron, ever the opportunist, manipulates Congress to oust Governor Wallace, whose failure to capture Billy has become a national embarrassment. The series uses these machinations to reveal what justice truly meant in 19th-century America — a word bent by wealth, ego, and the interests of a few men.

As with Hirst’s earlier work, history here becomes a stage for exploring morality. The system that hunts Billy isn’t about right or wrong; it’s about control. In that sense, his rebellion — his refusal to bow — becomes the purest expression of American resistance.

Betrayal, Faith, and the Shadow of Fate

Among the new faces in Season 3, Miguel Ortega emerges as a tragic double of Billy. Claiming to have turned against the tyrants of The House after his sister Isabel’s death — a story Dulcinea confirms — he appears genuine. Billy trusts him completely, unaware that Ortega is laying the groundwork for his downfall. What Billy believes to be a moment of triumph is, in truth, a trap.

It’s classic Michael Hirst storytelling: a meditation on hubris, loyalty, and the cost of faith. Like Vikings and The Tudors, Billy the Kid is less about historical accuracy and more about how power consumes those who chase it — even when they’re fighting for the right side.

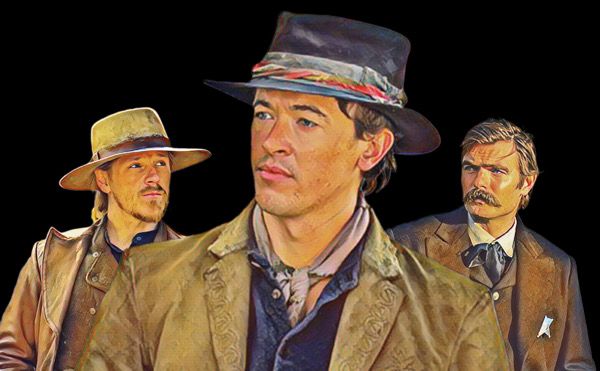

A Character and Actor Growing Side by Side

Much of the show’s evolution owes to Tom Blyth, whose own coming of age has mirrored Billy’s. “As I’ve matured and become more of a professional, so has Billy,” Blyth said recently. “I feel like I’m growing up alongside him.”

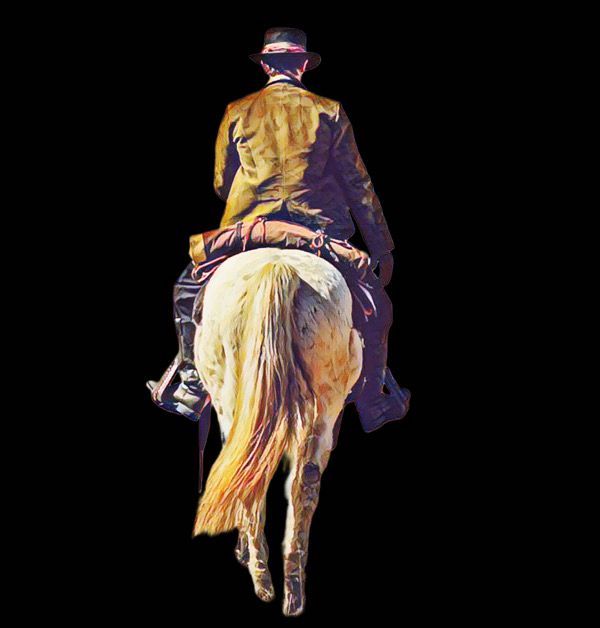

Three seasons in, Blyth’s transformation is remarkable. He performs nearly all of his own stunts — horseback chases, falls, rooftop runs, and gunfights — a commitment that lends the show a tactile, old-school grit. “In Season 1, I thought I was great,” he laughs. “Now they tell me I’m at a professional level. The wranglers even joke that I can work with them if acting fails.”

That self-deprecating humor masks a deep understanding of the role. His Billy is both magnetic and mournful — a man shaped by loss, still clinging to something like hope.

The Western as Mirror

Ultimately, Billy the Kid is not about gunfighters, but about identity. By stripping the myth of its glamour, Hirst crafts a meditation on the making of America — a place built on contradiction, ambition, and violence. Billy becomes a stand-in for the American dream itself: born from exile, sustained by rebellion, and doomed by its own legend.

As the show rides into its final sunset, its legacy is clear. Billy the Kid may never have commanded the audiences of Hirst’s earlier epics, but it earned something rarer — artistic integrity. It’s a western about what it means to live in the shadow of one’s own story, and to find humanity in the ruins of myth.

And perhaps that’s the greatest irony of all: by humanizing America’s most famous outlaw, Billy the Kid became one of the most honest portraits of what it means to be an American — or, more simply, to be human.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.