Nothing is more terrifying than losing control over what you consume. When a product — whether a drink, a medicine, or food — is deliberately adulterated, the horror doubles: beyond the risk of death, there’s the chilling realization that no one is truly safe.

The current case, which has already claimed the lives of more than 40 people in Brazil and hospitalized dozens with symptoms of methanol poisoning, is one of the worst kinds of mysteries. Because it could have been greed, negligence, stupidity — or all three combined.

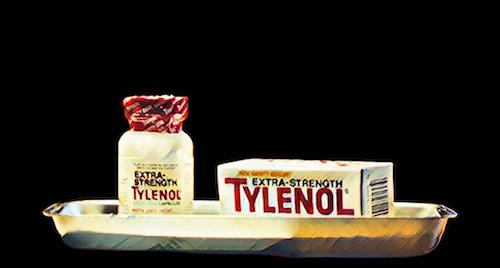

And for those who follow historical crimes and scandals, it’s impossible not to think of one of the most emblematic episodes of the 1980s: the Tylenol Murders.

The Tylenol Case: When Medicine Turned into Poison

In 1982, the United States was gripped by panic after a string of sudden, inexplicable deaths in Chicago. The victims — people of different ages, neighborhoods, and backgrounds — had only one thing in common: they had all taken Tylenol, the country’s most popular painkiller.

Within hours, investigators discovered that capsules of the medication had been laced with potassium cyanide.

Seven people died within days — among them a 12-year-old girl, a newlywed, and a young mother. The nation was horrified. The crime seemed senseless, and to this day, remains unsolved.

What followed was one of the largest recalls in corporate history: over 31 million bottles of Tylenol were pulled from shelves across the country. Johnson & Johnson, the manufacturer, faced the nightmare of seeing its brand associated with death — and yet, against all odds, it managed to do the impossible: rebuild public trust.

“Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders” — Netflix’s Chilling Revisit

More than forty years later, the story returned to the spotlight through Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders, a three-part Netflix docuseries released in May 2025. Directed by Yotam Guendelman and Ari Pines (Shadow of Truth, Buried) and produced by Joe Berlinger (Conversations with a Killer, Who Killed JonBenét Ramsey), the series revisits a crime that shattered the nation’s faith in the safety of everyday brands.

The documentary reconstructs the events of 1982, when America suddenly had to confront the unthinkable: that an anonymous killer could strike inside one’s own home through an ordinary product. The tainted capsules were quickly recalled, but the damage was irreversible — fear had seeped into the culture.

The investigation, involving the FBI, Chicago police, and federal prosecutors, stretched on for decades but never produced a conviction for the murders themselves. The prime suspect, James William Lewis, was arrested only for attempting to extort Johnson & Johnson. He denied being the killer until his death in 2023.

The series questions whether the truth was simply lost to time — or if there was a larger cover-up, exposing the vulnerability of major corporations when consumer trust collapses.

Johnson & Johnson’s Response: A Crisis-Management Blueprint

Johnson & Johnson’s reaction to the tragedy would become a landmark in corporate crisis management. The company immediately recalled every bottle of Tylenol, cooperated fully with authorities, and completely redesigned its packaging.

Out of this disaster came the tamper-evident seals and safety caps that are now standard on medicines worldwide.

The company’s campaign — “Trust is our most important ingredient” — became a rallying cry. Months later, Tylenol returned to the market and, remarkably, regained its leading position. Transparency, even in tragedy, had proven powerful enough to restore credibility.

Brazil, 2025: The Invisible Terror of Methanol

Four decades later, Brazil is living through a new version of that fear. Since September 2025, cases of methanol poisoning have been reported in multiple states. The Ministry of Justice and Anvisa (the national health surveillance agency) are investigating the origin of adulterated alcoholic beverages, especially unlabelled or counterfeit cachaças and distilled spirits.

Methanol is an industrial alcohol used in solvents and fuels — highly toxic to humans. Even a small dose can cause blindness, organ failure, or death. In the body, it metabolizes into formaldehyde and formic acid, destroying the nervous system and the liver.

Investigators suspect that some adulterated drinks may have come from clandestine distribution networks diluting products for profit. Others point to industrial malpractice in the handling of raw materials. For now, the truth sits uneasily between crime and negligence.

When Greed Becomes Poison: A Pattern of Contamination

The methanol crisis is not unique. Around the world, greed and carelessness have poisoned countless victims:

- 2012 – Czech Republic: more than 40 people died after drinking vodka and rum laced with methanol.

- 2018 – India: 150 deaths linked to counterfeit alcohol in Uttar Pradesh.

- 2006 – Brazil: falsified prescription drugs sold as “ghost capsules,” containing no active ingredients.

- 2020 – Mexico: mass deaths from adulterated alcohol during pandemic lockdowns.

Each of these cases reveals the same underlying truth: deliberate contamination always preys on trust — and on the most vulnerable consumers.

The Current State of the Brazilian Investigation

Authorities in Brazil have made multiple arrests and product seizures, and the Federal Prosecutor’s Office continues to track the distribution chain of industrial methanol. Suspicious brands have been banned, and Anvisa has tightened safety and traceability standards for distilled beverages.

Still, the core source of the contamination remains unclear, and investigators suspect a broader network of illegal suppliers. Meanwhile, bars and restaurants report sharp drops in alcohol sales, and legitimate producers are struggling to prove their authenticity.

Between Tylenol and Methanol: The Legacy of Fear

The Tylenol case taught the world that trust is an invisible ingredient — but an essential one. Once it’s broken, everything changes: how we buy, how we consume, how we believe in brands.

The methanol scandal in Brazil is different in substance but similar in trauma. It reminds us that the greatest danger doesn’t always lie in the product itself, but in human failure — in ethics, in oversight, in the pursuit of profit at any cost.

The poison isn’t only in the bottle. It’s in the indifference that lets it happen.

And just as in 1982, only time — and transparency — will tell whether it’s still possible to rebuild what’s been lost: the fragile trust in what we drink, take, and assume to be safe.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.