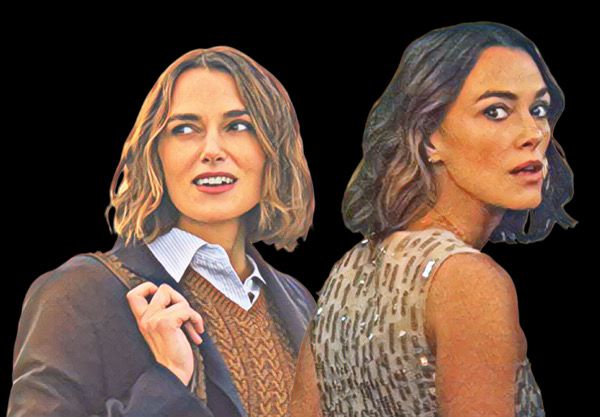

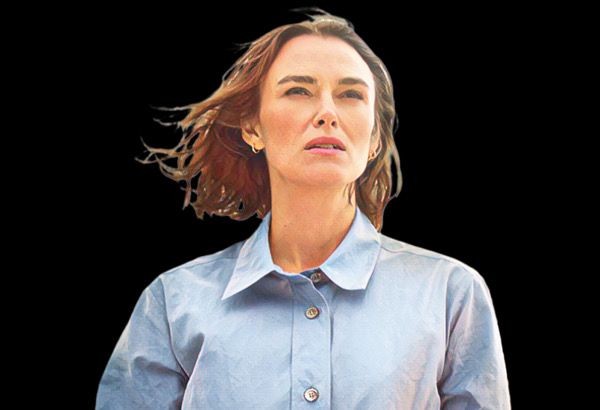

Next Friday, Netflix premieres the adaptation of the best-selling novel The Woman in Cabin 10, starring Keira Knightley — a promise of claustrophobic tension, nautical suspense, and the psychological drama of a woman no one believes. Watching Keira as Lo Blacklock feels like an invitation to revisit that suffocating narrative that blends luxury, isolation, and the terror of being unheard — and to see how it translates visually: the restless waters, the dim light in the ship’s corridors, the fear that is born from silence.

Since its release, The Woman in Cabin 10 has been placed in direct dialogue with other contemporary female bestsellers — stories that explore the female voice, the psychological, and the unreliable versus the illusory. Think of Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn and The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins: women narrators marked by instability, doubt, fragmented memory, and the tension between what they experience and what others want them to believe they experienced. Ware absorbs that tradition: she offers a narrator who, at first glance, seems fragile and emotionally shaken — and yet, at the core of the story, becomes the lucid witness of a crime no one wants to acknowledge.

But Cabin 10 goes further — and that’s where it gets fascinating: the hidden parallels, the cultured and symbolic inspirations that thread through the novel. Because more than “a crime at sea,” Ware brings to the surface myths of identity, duplicity, female invisibility, and the power of gaslighting. ⚠️ Spoilers ahead.

1. The Journey as Inspiration — The Sea as a Kingdom of Silence

In interviews, Ruth Ware said much of the book’s unease came from her own experiences at sea — that feeling of being on open water, isolated, with no escape, imagining something sinister happening and realizing that no one could run, no one could rescue you in time. The idea of an “unprovable crime” was born there: you witness something, but every piece of evidence can be erased or disputed by those in control — the crew, the ship logs, the passengers.

That existential fear — the sea as a silent graveyard — is a recurring myth in suspense literature: water swallows, conceals, erases. In Cabin 10, it becomes as much a character as any of the humans aboard.

2. Real Cases — The Disappearance That Never Makes Headlines

Although Ware never named a single true story as a direct source, many have linked the novel to the real-life case of Amy Lynn Bradley (1998), who vanished from a Caribbean cruise — last seen on the cabin balcony before disappearing without a trace. Her tragedy became infamous for its ambiguous investigation, conspiracy theories, and official silence.

That kind of disappearance clings to the imagination: something so ordinary — a leisure trip — turning into a nightmare, and worse, something the world chooses not to investigate properly, to dismiss as error, delusion, or confusion. Ware draws on that atmosphere of “uninvestigated suspicion,” of crimes hidden beneath a polished surface of luxury.

3. Hitchcock, the Double, and the Rewritten Crime

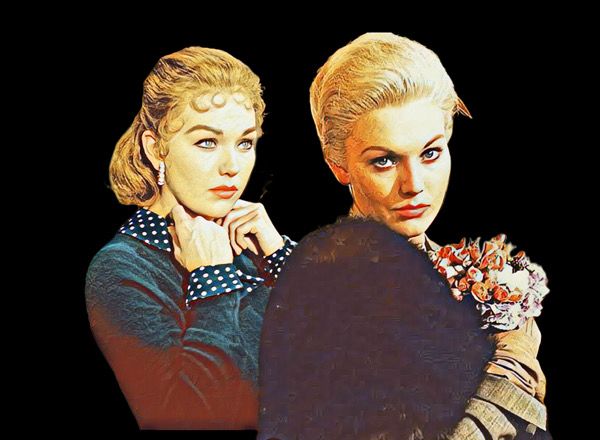

Here, your insight — the Hitchcock influence — becomes crystal clear. The Woman in Cabin 10 feels like a disguised tribute to Alfred Hitchcock’s cinema, especially films like Vertigo and The Lady Vanishes.

- Identity swap/substitution: In Vertigo, we see a dead woman, a substitute trying to take her place, manipulation of image and memory. In Cabin 10, Anne Bullmer is sick, dead, or undefined, and Carrie is hired to replace her — a cruel and symbolic act of erasure: someone who lived, who felt alive, who was used as a puppet, and then discarded.

- Gaslighting/disbelief of the narrator: Hitchcock loved to play with perception — and with the internal doubt of his heroines. In The Lady Vanishes, a woman witnesses another woman disappear on a train — and no one believes her. Ware mirrors that pattern: Lo says she saw something, heard something, someone thrown overboard — but she’s dismissed as unstable, paranoid. The doubt sets in: has she lost her mind? Is she making it up?

- Protagonist with trauma/vulnerability: Hitchcock’s heroes and heroines always have a fracture — fear, guilt, trauma — something the antagonist exploits. Lo carries her own: a recent break-in at her London flat, sleepless nights, anxiety. Hitchcock loved psychological characters like that (Spellbound comes to mind).

So Ware doesn’t simply write a thriller inspired by Hitchcock — she symbolically recycles his cinematic obsessions inside the female psyche: distorted identity, a conspiratorial world, constant suspicion, the “crime that can be denied.”

That same device echoed through 1980s neo-noir thrillers like Body Double, which played on voyeurism, substitution, and illusion.

4. The “Pain of Female Invisibility” — Lo and Carrie as Mirrors

Here lies the novel’s most profound symbolic core. Lo and Carrie are imperfect reflections of one another:

- Lo represents the woman who suffers, who’s been wounded and dismissed — yet insists on her version of truth. She’s a voice crying out against collective silence, against institutions that prefer disbelief.

- Carrie represents the woman used as a prop to cover another man’s crime, a disposable double who lives on the margins, forced into a role that isn’t hers.

Together — or in opposition — they dramatize the female double: Who is real? Who has the right to exist fully? Who will be believed?

Carrie’s death or disappearance — and the novel’s ambiguity about whether she’s still alive — reinforces the myth of the vanished woman, the woman who’s erased by the very mechanisms of male power, manipulation, and denial.

The sea, again, operates as the feminine unconscious — a space where memories sink, where truths are swallowed, where women disappear so that official versions can remain intact.

5. Between the Contemporary and the Classic — The Reimagined Female Thriller

Returning to Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train: those novels redefined the modern female thriller — women as unreliable narrators, inverting expectations, and exploring gendered power and control of narrative. Ware builds on that legacy but “retrofits” it with the British classicism of a closed-room mystery. She fuses the modern psychological fragmentation and self-doubt with the old-school confined setting, limited cast, and tension dictated by isolation.

Thus, The Woman in Cabin 10 breathes in two worlds at once: modern and classic, suburban and Gothic, feminine and Hitchcockian — inspired by real fears of vanishing without a trace. And the Netflix adaptation, starring Keira Knightley, promises a new visual lens: mirrors, narrow hallways, dark waters in the distance, and the ghostly face of Carrie — alive or not, forever haunting.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

5 comentários Adicione o seu