Some songs don’t age because they were never meant to belong to a single moment.

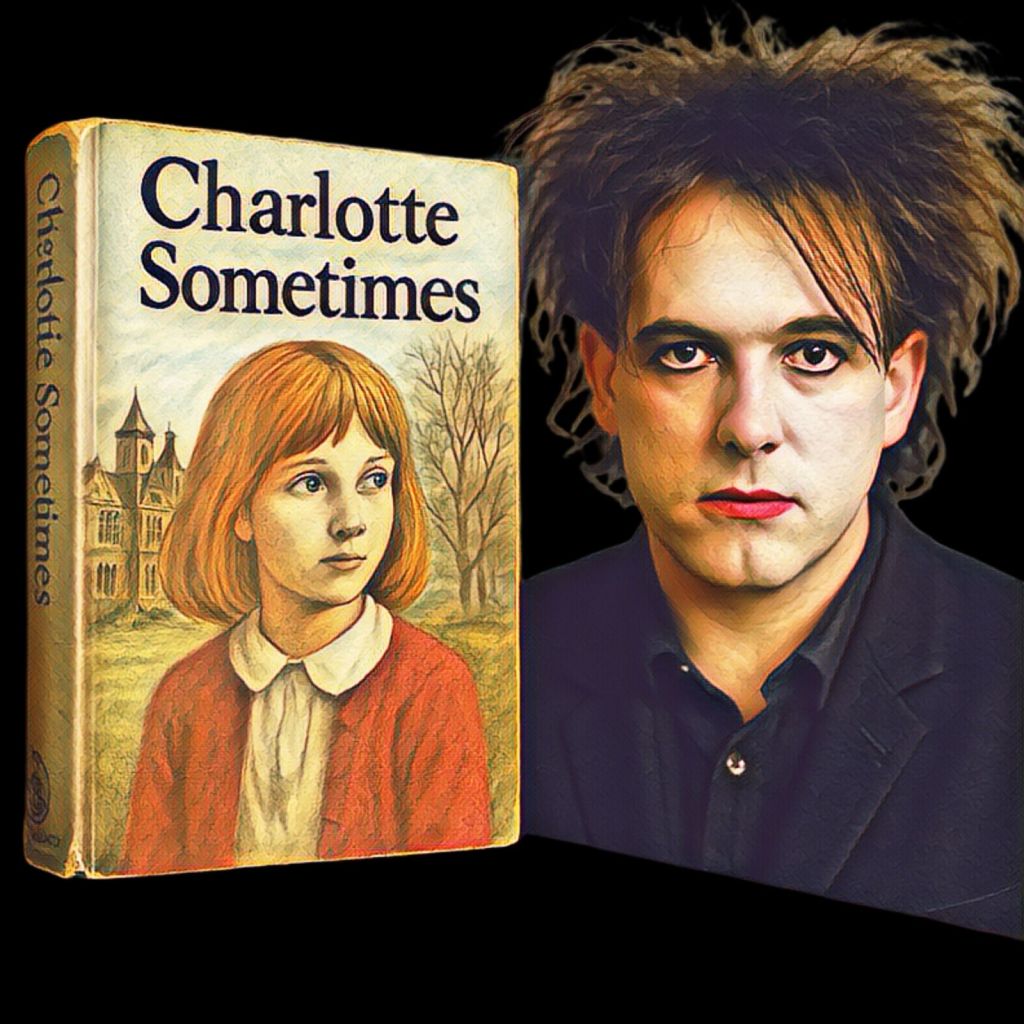

Charlotte Sometimes, released on October 9, 1981, is one of them. By then, The Cure had already crossed into the territory of the strange and the melancholic — Faith had left its pale imprint, and Pornography was on the horizon, waiting to shatter whatever light was left. In between those two extremes, Robert Smith wrote one of the band’s most delicate and haunting pieces: a song about the dissonance between body and soul, about waking up in another time and not recognizing who you are anymore.

The story began years before, in the quiet pages of a forgotten British novel.

Charlotte Sometimes, written by Penelope Farmer and published in 1969, tells the story of a girl who, upon falling asleep in a new boarding school, wakes up forty years earlier — during World War I — in the body of another girl named Clare. At night, the two switch places, sharing the same bed, the same world, and eventually, the same self. The boundaries between them dissolve. Charlotte becomes Clare; Clare becomes Charlotte. The novel is about mirrors, memory, and the fragile idea of identity — everything Robert Smith would one day translate into sound.

Smith first heard the story as a child. In Crawley, Sussex, his older brother used to read aloud to him and his sisters before bed. One of those bedtime readings was Charlotte Sometimes.

When Smith finally met Penelope Farmer decades later, he told her:

“My elder brother used to read to us at bedtime. I was about twelve or so.

Your book was one of them. It never got out of my head.

Once I got into music, I wanted to make a song about it.”

What haunted him wasn’t just the story — it was the way it was heard. The rhythm of a voice coming from the dark, the hypnotic cadence of words that hover between waking and dreaming. It was an auditory memory, and that’s exactly how he rewrote it: as if trying to dream again something that had once held him still.

Penelope Farmer — herself an identical twin — was obsessed with doubles and reflections.

In Charlotte Sometimes, she turned childhood into a metaphor for self-erasure. The boarding school, with its echoing halls and neatly made beds, becomes a living organism, a place where identity dissolves. Time travel, in her story, is not scientific — it’s emotional. Charlotte slips through decades the way we slip through the stages of our lives: almost unknowingly, until one day we wake up as someone else.

When the book was published in 1969, it was shelved as a children’s novel, but later critics rediscovered it as something more complex — a meditation on memory, loss, and the way growing up means saying goodbye to the versions of ourselves that no longer exist. It remains one of the most quietly melancholic works of British fantasy.

When Robert Smith wrote Charlotte Sometimes, he called it a “straight lift” — a direct adaptation. And it was. Many lines in the song are lifted almost verbatim from the book.

Farmer wrote:

“All the faces, all the voices blur, change to one face, change to one voice.”

Smith sang:

“All the faces, all the voices blur / Change to one face, change to one voice.”

The song opens mid-dream — no exposition, no context, just confusion. It’s the precise moment when Charlotte begins to lose her sense of self.

Recorded in July 1981 and released that October, with Splintered in Her Head as its B-side (itself named after another line from the novel), the single feels like a bridge suspended between two worlds: the sparse, meditative sound of Faith and the feverish despair of Pornography. Smith’s voice seems to come from an empty room, echoing against itself. The bassline is a pulse that never stops. The melody circles itself like a thought looping through memory.

“Sometimes I’m dreaming, where all the other people dance…”

— as if life were something that happens elsewhere, to someone else.

The video was filmed at Holloway Sanatorium, a Victorian mental asylum outside London. It’s an eerie, perfect setting. A young woman — Charlotte — wanders through long corridors lined with mirrors, her reflection blurring as she moves. Smith watches from a distance, motionless, almost spectral.

Everything in the video — the walls, the windows, the echo — feels alive, haunted by repetition. Even the cover of the single mirrors the theme: a distorted photograph of Mary Poole, Smith’s girlfriend and future wife, her face familiar yet unrecognizable. The same image, undistorted, would reappear years later on Pictures of You, linking love and time in one unbroken reflection.

When Smith and Farmer finally met, she was struck by how candid he was. She had been mildly irritated at first, realizing he had quoted her work so directly without permission. But when he handed her a copy of the book to sign, he said, smiling,

“You can see how inspired I was — how I nicked it.”

She later wrote that seeing her story reborn as a song felt “like finding a child lost in time.”

It’s a perfect description — not just of the song, but of the strange persistence of art itself.

Because Charlotte Sometimes is exactly that: the rediscovery of something that never stopped aching. It’s a song about displacement, about waking up in a world that no longer fits, about realizing that maybe what we lost was never real to begin with. Forty-four years later, it remains strikingly modern — a portrait of fragmented identity, of selves scattered across moments and memories. Charlotte’s confusion is our own: living in multiple realities, forgetting which version of us is the original.

Robert Smith turned a childhood story into a hymn about forgetting and becoming.

Penelope Farmer wrote about a girl who fell asleep at one time and woke in another; Smith wrote about the man who never fully woke up. That’s why Charlotte Sometimes still resonates: because it whispers the same quiet truth — that time isn’t linear, that identity is a mirage, and that some dreams, the ones that matter most, never really end.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.