Nothing could feel more timely, after the massive success of the series Monster: The Ed Gein Story, than to revisit an important milestone in film history: the 65th anniversary of Psycho.

In 1960, Alfred Hitchcock didn’t just release a film — he changed the grammar of cinema itself. The origin was Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel Psycho, loosely inspired by the real-life crimes of Ed Gein. Hitchcock bought the rights anonymously, sending his assistants to purchase every available copy in bookstores so no one would guess the twist. That obsessive secrecy defined what would follow: Psycho was an experiment in total control — of information, of narrative, and of audience reaction.

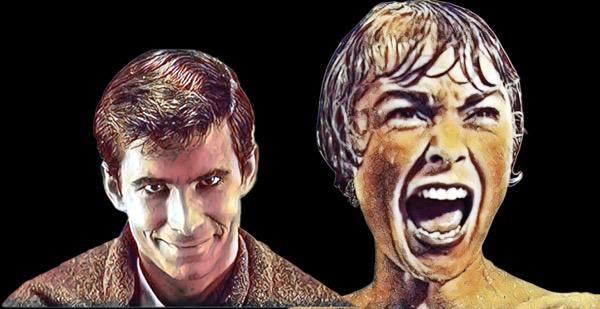

Netflix’s recent Monster: The Ed Gein Story revived the link between the Wisconsin killer and Norman Bates, Bloch’s fictional murderer immortalized by Anthony Perkins. But the series overdramatizes the connection, depicting Hitchcock as a voyeuristic director “recreating” Gein’s house and crimes — an exaggeration unsupported by history. The influence is thematic, not literal. What Hitchcock did was transform Gein’s rural grotesque into a psychological labyrinth: a horror of guilt, repression, and voyeurism, set not in a barn, but in the mind.

The Revolution: From Production to Marketing

Psycho was made for just under $1 million, shot in black and white with the TV crew from Alfred Hitchcock Presents, after studios refused to back what they saw as a vulgar, risky story. Hitchcock financed it himself, trading glamour for experimentation. It became the director’s most radical gamble — and his most profitable one.

Then came the marketing masterstroke: no one was admitted after the movie started. It was unheard of. Theaters enforced punctuality, queues wrapped around blocks, and suspense became a shared ritual. The campaign turned Psycho into the first true cinematic event — a precursor to the spoiler-free, premiere-driven marketing that defines blockbusters today.

It also shattered taboos. The famous shower scene flirted with nudity, and Hitchcock inserted a simple flush of a toilet — something never shown under the strict Hays Code. Even the decision to film in black and white had layers: partly to cut costs, partly to hide the “blood” (actually chocolate syrup), and mostly to intensify the abstraction of violence. Psycho didn’t show; it suggested — and that suggestion was more shocking than anything explicit.

Style as Substance: Editing, Sound, and Control

The shower scene — seventy cuts in forty-five seconds — is film language in its purest form. Hitchcock turned editing into violence, rhythm into fear. Bernard Herrmann’s all-string score sliced through the soundtrack like a knife, creating one of the most recognizable sounds in movie history. Originally, Hitchcock wanted the scene to be silent; after hearing Herrmann’s composition, he admitted the composer had improved the film beyond measure.

From that moment on, cinema changed. Psycho demonstrated that horror could be art — and that suggestion, not spectacle, was the ultimate instrument of terror. The film’s DNA runs through The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Halloween, Silence of the Lambs, Get Out, and every thriller that treats fear as psychological architecture rather than just bloodshed.

The “Last” Hitchcock Hit?

Commercially, Psycho was a phenomenon, earning over $50 million and becoming Hitchcock’s biggest box-office success. But it wasn’t his last. The Birds (1963) also soared financially and critically. What Psycho closed was not his career peak, but an era — the last breath of the classical Hollywood system before the auteur era truly began.

After Psycho, Hitchcock became even more experimental and controlling, clashing with studios and censors alike. His meticulous manipulation of audience emotion — perfected here — would inspire generations of filmmakers and mark the pivot between the Golden Age and the modern psychological thriller.

The Ill-Fated 1990s Remake

In 1998, Gus Van Sant attempted a shot-for-shot color remake with Vince Vaughn and Anne Heche. Conceived as a formal experiment, it ended up proving the opposite: Psycho cannot be reproduced. Without its context — the censorship, the taboos, the black-and-white abstraction — the film became a hollow exercise, met with commercial disappointment and critical ridicule.

Van Sant’s version inadvertently underscored Hitchcock’s genius: that Psycho wasn’t great because of its plot, but because of how it was filmed. Every cut, every sound, every silence was calibrated for 1960 — and still feels dangerous today.

Cultural Aftershocks

For over 65 years, Psycho has never faded. It spawned sequels, a television prequel (Bates Motel), countless parodies, homages, and academic studies. Its fingerprints are visible in David Lynch’s surrealism, Brian De Palma’s voyeurism, and Jordan Peele’s social horror. It remains the most dissected film scene in history, the subject of entire documentaries (78/52) and film theory classes worldwide.

More than a horror movie, Psycho is a meditation on repression and identity — on what happens when the boundaries between watcher and watched dissolve. Hitchcock made the audience complicit: we peep through the hole, we clean up the mess, we share Norman’s guilt. That’s why the film never stops working — it implicates us.

Why It Still Feels Modern

Sixty-five years later, the film’s power endures because it’s not about gore or shock value. It’s about control — visual, emotional, moral. Hitchcock weaponized editing, music, and secrecy as narrative tools, inventing a form of cinematic storytelling that feels as fresh in 2025 as it did in 1960.

Its innovations still define our viewing habits: spoiler-free marketing, controlled pacing, and audience immersion. The black-and-white austerity, once a necessity, now reads as sophistication. Even the flush of a toilet, once scandalous, stands as a symbol of realism breaking through repression.

The Film That Still Watches Us Back

At 65, Psycho remains the dividing line between old Hollywood and modern cinema — a masterpiece of suggestion that turned limitations into language. Its violence lies not in the knife but in the cut, not in the scream but in the silence after.

Hitchcock taught the world that the scariest place isn’t the Bates Motel, but the human mind. And decades later, when the violins start to shriek, we still flinch — not because of what we see, but because we realize we’re the ones watching.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.