The Marquise de Merteuil is one of the most powerful characters ever created in literature — and also one of the most misunderstood. Since Pierre Choderlos de Laclos published Les Liaisons Dangereuses in 1782, critics and readers have tried to decipher who she is, where she comes from, and what drives her. Over the centuries, she has been labeled a villain, a victim, a feminist, diabolical, a libertine, cold, and passionate. None of these categories truly fit what Laclos wrote. The real Merteuil is a woman born from intelligence and calculation, not trauma. She is a free mind trapped in a female body — and that is precisely the scandal of the novel.

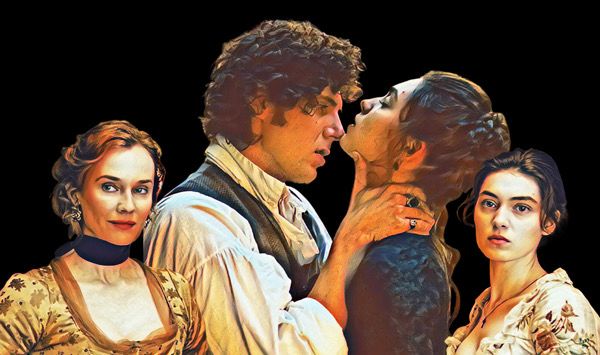

I say this because we’ve had the play Dangerous Liaisons, the film of the same name, Valmont, then the failed attempt to portray her youth (Dangerous Liaisons, 2022), and now A Seduction (originally announced as Merteuil). The creative liberties taken with her story worry me, because the focus on her sensuality reduces her to a woman perpetually seeking revenge — and Merteuil was always far more than that. She was modern and daring, even two and a half centuries later.

Intelligence as Vengeance

In the novel, the Marquise’s past is never told linearly. It emerges, like everything else in Dangerous Liaisons, through letters. It’s in the famous Letter 81 that she finally speaks of herself. Writing to the Vicomte de Valmont, her accomplice and rival, Merteuil reveals the secret behind her reputation: everything about her is studied.

Raised by a strict aunt in a rigid education, she learned early that women were trained to obey, to please, and to keep quiet. While the world thought her docile, she was learning the opposite — how to read gestures, silences, weaknesses, and to use the mask imposed upon her as a weapon. “I was born to avenge my sex and to master yours,” she writes. It’s perhaps one of the most radical lines ever written for a fictional woman in the eighteenth century. She doesn’t seek pity; she seeks power. And she achieves it through the only means available to her: dissimulation.

The Art of Pretending: The Mask as Weapon

Merteuil discovers that control means freedom. She marries without love but turns marriage into a shield: while her husband lives under the illusion of a virtuous wife, she observes and calculates. When she becomes a widow, she realizes that widowhood is the greatest liberation. The title of “respectable widow” becomes the perfect disguise.

“I decided to live in such a way that everyone would believe me incapable of error, and yet that nothing would be forbidden to me,” she writes. That sentence defines not only her philosophy but the survival mechanism of so many women of her time — and of ours. She doesn’t need a tragic past, a man who hurt her, or a miserable childhood. Merteuil’s trauma is the patriarchal system itself, and the way she resists it is by mastering the game men invented to dominate her.

Merteuil and Valmont: United, Never Equal

Unlike Valmont, who plays for vanity and pleasure, Merteuil plays for control and respect. He is the classic libertine — a man who delights in manipulating emotions — while she is a strategist who understands the power of language and appearances. He needs an audience; she needs secrecy. That’s why their relationship is a war disguised as an alliance. They understand each other because they speak the same language of cynicism and seduction, but they are never equals. Valmont is impulsive and seeks glory; Merteuil is rational and seeks mastery. When he falls in love and loses himself, she remains faithful to her own code: never to be captured — not by love, nor by guilt.

Merteuil’s destruction at the end of the novel — the illness, the scandal, the ruin — is less a moral punishment than a narrative necessity. Laclos, though an Enlightenment thinker, still wrote within the conventions of his time. A woman so lucid, intelligent, and free could not be allowed to survive unpunished. But her downfall does not erase her triumph. Until the very end, Merteuil refuses to confess, to beg forgiveness, or to be reduced. She is punished for what offends most: intellectual and sexual independence.

Over the centuries, this character has become a challenge for anyone trying to adapt to her. Cinema and television rarely tolerate a woman who doesn’t “explain herself.” Thus, modern versions attempt to justify Merteuil with backstories, traumas, or romances.

In Stephen Frears’s 1988 adaptation, Glenn Close gives the character an almost tragic dimension: a woman who once loved Valmont and was betrayed. The story implies that her coldness stems from resentment. It’s brilliant, but it betrays Laclos. The original Merteuil never loved Valmont. She admires him as a rival and despises his weakness when he succumbs to emotion. Milos Forman’s Valmont, with Annette Bening, follows the same pattern, changing the ending and moving further away from the original novel.

Modern “Updates”: When They Try to Explain Merteuil

The Starz series (2022) goes even further, turning Merteuil into a woman of humble origins who rises through manipulation — a kind of modern antiheroine shaped by social injustice. It’s narratively effective but erases the essence of the character: Merteuil is not the product of misery but of privilege and lucidity. She is the mirror of the system she subverts.

The Netflix French version (2022), Les Liaisons Dangereuses, turns Valmont and Merteuil into high school teenagers, Célène and Tristan, in an Euphoria-style retelling, moralistic in tone. There, power is born of emotional pain, not intelligence. The original Merteuil never needed to be wounded to become dangerous.

These distortions also appear in how the story itself is usually retold:

In the novel, the play, and the 1988 film, the plot begins with a Marquise de Merteuil offended by a former lover, the Comte de Gercourt, who left her to marry a young virgin, Cécile Volanges. To humiliate him, she enlists another ex-lover, the Vicomte de Valmont, a notorious libertine, to seduce Cécile before the wedding. The problem is that Valmont is more interested in breaking the virtue and serenity of Madame de Tourvel, which infuriates Merteuil even more. After all, she — a great lover, beautiful and intelligent — “loses” to obedient, unremarkable women. By provoking Valmont, she seeks to destroy him and Gercourt in their own games. And she succeeds.

The Marquise de Merteuil never says she loved Valmont in Les Liaisons Dangereuses. In none of the 175 letters does Laclos make her express love, romantic jealousy, or emotional desire for him. What exists between them is intellectual admiration, rivalry, complicity, and vanity — but never love. The misunderstanding arises from adaptations — especially Frears’s 1988 film, with Glenn Close and John Malkovich — which turn their duel into a story of repressed passion. It’s a seductive cinematic idea, but it does not exist in Laclos’s text, and it has tainted nearly every adaptation since.

Another recurring mistake: Merteuil was indeed an orphan, but Pierre Choderlos de Laclos never suggests she came from humble origins; on the contrary, everything indicates she belonged to the French nobility, raised with the education and manners of the eighteenth-century elite. Both the Starz series (which even places her in a brothel before marriage) and HBO’s A Seduction present her as an inexperienced young woman trained to become a courtesan. Nothing could be further from what the book described — and shocked readers with.

Eighteenth-century French society dealt with courtesans in a double standard: they were tolerated and openly acknowledged as such. The shock of Dangerous Liaisons came precisely because Merteuil was a noblewoman, outwardly virtuous but in truth sexually experienced and liberated. She always lived among the aristocracy, receiving the proper education of a woman of her rank — religion, etiquette, music, dance, and silence. And behind that façade, she was a libertine.

Since the 1988 film, every version has also insisted on giving Merteuil a mentor — a woman who “trains” her, mirroring what she later does with Cécile. Nonsense. In the book, she mentions being raised by a “strict old aunt,” an unnamed figure — not Madame de Rosemonde, who is Valmont’s aunt. Yet, in A Seduction, it is precisely Rosemonde, played by Diane Kruger, who becomes Merteuil’s teacher in the art of seduction.

The problem with this revision is that Madame de Rosemonde represents the complete opposite of the Marquise de Merteuil. She is kind, honest, lucid, and, within her time, the moral voice of the novel. Though she loves her nephew, she perceives his emptiness and corruption, and even laments the influence Merteuil has over him.

Rosemonde is also Madame de Tourvel’s confidante — it is to her that Tourvel writes when she despairs between desire and duty. Thus, Rosemonde functions as a bridge between the moral and immoral worlds of the story: she is the refuge and redemption space that libertines pretend to respect but ultimately profane. She is what remains of a pre-revolutionary moral order, an echo of France before the aristocracy’s decay. Valmont uses his aunt as a shield of respectability — he writes his letters from her château, exploiting her trust and innocence to mask his schemes. In other words, Rosemonde is Valmont’s alibi. He knows that near her, no one will suspect him.

By inverting Rosemonde’s moral values — and even her personality — the new adaptation commits the same kind of anachronism we saw in The Buccaneers: a lamentable mistake.

The Scandal of Lucidity

All these versions try to solve the “problem” Laclos posed and never answered: what happens when a woman is more rational, colder, and more strategic than the men around her? The eighteenth century could only punish such a woman. The twenty-first still tries to explain her, as if female autonomy required emotional justification. Laclos, however, created Merteuil not to be understood but to be feared. She is the logical product of a hypocritical society — a monster born of lucidity. The true scandal is not what she does, but what she thinks.

Merteuil is the Enlightenment turned inside out. While philosophers wrote about liberty and equality, she practiced both in secret, between bedsheets and letters. She is a woman who thinks with her mind and acts with her body — and that, in 1782, was intolerable. In the end, when the mask falls, the world destroys her not for her crimes but because she dared to live like a man, without apology.

The Woman Who Pretended to Exist

That is why, even punished, she remains invincible in memory. No modern version has captured what Laclos did: the power born of thought, the desire born of observation, the irony of a woman who learned to pretend to exist — and in doing so, became truer than everyone who judged her.

This is the real Marquise de Merteuil — not the betrayed lover nor the victim of society, but the architect of her own destiny. A woman who turned submission into strategy, silence into language, and appearance into a weapon. Instead of being remembered for what she destroys, she should be remembered for what she reveals: the hypocrisy of a world that still fears women who think.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

Dear Ana: I stumbled on your post in a Google search, and found it absolutely fascinating! (It’s great to meet someone who obviously loves Les liaisons dangereuses as much as I do.) Thank you, in particular, for pointing out that giving Merteuil a female mentor who grooms her in libertinism is completely contrary to the novel. (You make a small error, however: in the novel Merteuil says she was raised by a “strict mother,” not an aunt.) Obviously the new HBO series completely revises the character of Rosemonde; but since it bills itself as “inspired by” Liaisons, they have the freedom to do that. The Starz series, which you mentioned, had a very good cast and was visually beautiful, but I found the story disappointing — it was far too melodramatic, and it claims to be a “prequel” to Liaisons while diverging wildly from the book. We actually know Merteuil’s backstory in the novel, and it certainly doesn’t include being an orphaned housemaid or a prostitute! In fact the fascinating thing about her in the novel is that she has, by 18th C standards, an entirely conventional childhood and youth: she’s an upper-class girl who is raised at home and then married off to an older man at 15 or 16. It’s her mind and personality that makes her extraordinary: nothing “made her this way.” Valmont’s backstory made no sense to me either: there is absolutely nothing about the character in the book to suggest that he has ever experienced any kind of privations. The casual assumption of privilege is at the core of the character.

The new series looks interesting, and I may well enjoy it, but it’s certainly not Liaisons.

I do disagree with you that there is absolutely nothing in the novel to suggest that Merteuil loves Valmont; I think it’s one of the novel’s many ambiguities. I discuss that in a recent post on my own blog.

I also thought you might be interested in an essay about Liaisons I wrote almost 3 years ago: Love and Libertinism

Would love to chat with you about it some more!

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa