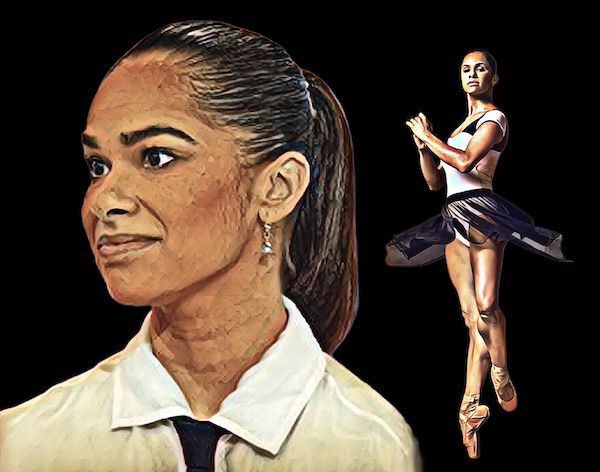

When Misty Copeland announced that she would retire from the stage in 2025, it was news again — not simply because of her farewell, but because she had reconfigured the stage around a structural prejudice that the American Ballet Theatre, like so many other companies, had maintained for decades. It was only in 2015 that Misty was promoted to principal dancer, becoming the first Black woman in the company’s history to hold that title. And she remains the only one, even ten years later.

It makes sense, because her story is, at once, a gesture of beauty and of rupture: the ballerina who arrived “too late” to ballet and still became the symbol of an era in which the Black body moved from the margins to the center of the stage — not as an exception, but as a reflection of everything art can still be.

Born in 1982 in Kansas City and raised in Los Angeles, Misty didn’t start dancing until she was thirteen, in a free class at the Boys & Girls Club. That was where she discovered not only talent but vocation — a musicality born of instinct and a sense of control that seemed innate. Within months she was dancing on pointe; within years, the teenager of modest background and turbulent family life became an unlikely promise in one of the most rigid worlds in art. The Black girl who started “too late” crossed the line of the impossible.

In 2012, choreographer Alexei Ratmansky created Firebird for her — the first ballet conceived especially for Misty’s body, energy, and stage presence. Inspired by the Russian legend, the piece became a personal metaphor: the magical bird that burns and is reborn. Misty rehearsed while battling six stress fractures in her tibia, danced through pain, and ended the season with the audience on its feet. It was more than a performance; it was a manifesto. Ratmansky saw in Copeland a raw strength and a kind of femininity that didn’t fit traditional molds — a tension between power and grace that would come to define her artistry.

Three years later, in 2015, Misty Copeland broke the final glass ceiling: she became the first Black woman to achieve the rank of principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre in its 75-year history. Her debut in Swan Lake was met with collective emotion — not only for the performance but for what it represented. That night, when she danced Odette/Odile, Misty didn’t just command the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House; she redrew it. The image of a Black woman inhabiting that role, in a repertory long reserved for an idealized whiteness, was a historical gesture that transcended technique. It was the moment when art and symbol became inseparable.

Misty’s dancing has always provoked passionate reactions. Critics recognized her physical virtuosity — the clean jumps, perfect balance, instinctive musicality — and her ability to fill the stage with presence, even in smaller roles. Her athletic power was undeniable, but her true signature lay in emotion. Misty danced with her whole body — with her shoulders, her breath, her gaze. She was not a ballerina who floated; she burned. Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times once described her dancing as “a bodily radiance, an emotional pulse that surpasses the perfection of lines.” Perhaps that’s the most accurate praise: Misty was not a ballerina of porcelain, but an interpreter of living flesh.

Yet the reactions also revealed how ballet remains resistant to difference. Some critics — especially traditionalists — pointed to supposed shortcomings of line or lightness, comparing her to European body types. Her shorter legs, defined musculature, physical density — all the things that made her unique — were read as “imperfections” under an outdated aesthetic metric. The truth is that Misty never danced to fit a mold. She danced to break it. And the audience understood that long before the critics did.

She always knew she carried two dances: the one she performed onstage and the one she fought offstage. Onstage, she defied the ideal of weightless grace; offstage, she confronted the symbolic weight of being “the first.” Her rise coincided with the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and her image — on magazine covers, in ad campaigns, music videos, and even performing alongside Prince — turned ballet into a cultural conversation. Misty became a visible heroine of an art long made invisible. And even if the system benefited from her shine, her personal triumph did not dissolve structural exclusion: ten years after her promotion, the American Ballet Theatre still has no other Black female principal.

Misty transformed this tension into concrete action. In 2021, she founded the Misty Copeland Foundation, dedicated to access and diversity in dance. Its BE BOLD program offers ballet classes with live music in public schools, and its extensions — Next Steps and Be Bolder — expand this democratization for underprivileged youth and adults who see in dance a path to health and belonging. Her mission is clear: to rebuild ballet from the ground up, not just to shine at the top. “Black and brown communities want to be in these spaces,” she told The New York Times. “They just need to see themselves, to feel that they’re being invited in.”

At the same time, Misty challenged the small symbols that sustained exclusion: she painted her pointe shoes to match her skin tone — a simple but revolutionary act. Today, major brands produce pointe shoes in multiple shades. Small victories that, multiplied, reshape the world.

In 2025, at forty-three, Misty Copeland leaves the stage with rare serenity. Her final performance at Lincoln Center was broadcast live — a public celebration of a cycle that began in a community gym. It’s impossible not to think of the circularity of it all: the girl who once danced barefoot in Los Angeles closes her career at the center of American ballet, applauded by an audience she helped diversify. Her farewell is also a beginning.

There is, of course, an uncomfortable question: what comes after Misty? Her legacy shines so brightly that it exposes the absence of others like her. The ABT still has no Black female principal, and the ballet world is again facing contraction — fewer funds, fewer inclusion policies, less urgency to open its doors. Misty’s representativeness revealed both the best and the worst of the system: what can flourish when there is space, and how fragile that space remains when it depends on exceptions.

Even so, it’s undeniable that the landscape has changed. Young Black dancers now grow up with Misty’s image onstage, in storefronts, on magazine covers, on screens. It’s a quiet transformation, but a profound one. What Misty opened cannot be closed again. As former dancer Theresa Howard said, “The absence of Black dancers was never accidental.” Now that the truth is known, there is no going back.

Misty Copeland was an exceptional ballerina, but she was also a mirror, a portal, and a scar. She danced like someone fighting and fought like someone dancing. What will endure, more than technical perfection, is the gesture of occupying a space denied for centuries and turning it into a home. Ballet — the art of balance and lightness — found in her a new gravity: the gravity of a body that bears weight, that resists, that inspires.

And perhaps that is what makes Misty Copeland unforgettable — not her form, but what she made of form; not the step, but the meaning; not the lightness, but the weight of the history she carried and returned through movement. When she takes her final bow, the applause isn’t just for the end of a career. It’s for the beginning of another kind of beauty.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.