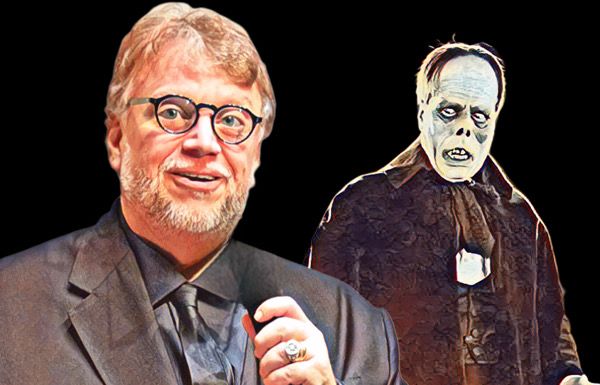

Guillermo del Toro has always been more than a storyteller — he’s a restorer of myths. His cinema breathes compassion into darkness, turning monsters into metaphors for the pain of being alive. In 2025, with the release of his long-awaited Frankenstein, del Toro reaffirmed what cinephiles already knew: no one today translates shadows into emotion quite like him. So when he recently confessed his wish to “revisit” The Phantom of the Opera, it sounded not like a whim but an inevitability. Few characters in literature are as perfectly aligned with his vision as Erik — the disfigured genius who lives beneath the Paris Opera, in love with music and terrified of the human gaze.

The Book and the Birth of a Myth

Before it became a myth, The Phantom of the Opera was a work of investigative imagination. Its author, Gaston Leroux, was a crime reporter and theatre critic in turn-of-the-century Paris. Blurring fact and fiction, he drew inspiration from real legends surrounding the Palais Garnier, the grand opera house inaugurated in 1875. Locals whispered about a hidden lake beneath the stage (which truly exists, used even today by firefighters for training), secret corridors, a cursed theatre box, and even a skeleton found during renovations. Leroux gathered all these tales into a gothic mystery and published them in serialized form in Le Gaulois between September 1909 and January 1910, before releasing the story as a novel that spring.

Leroux’s genius was to present the tale almost as an exposé. He opened the book by claiming to have discovered documents proving that Erik — the so-called Phantom — had really existed. That mixture of journalism, suspense, and melancholy birthed a new kind of horror: one rooted not in the supernatural but in loneliness and longing.

1925: The Birth of a Cinematic Icon

When Hollywood adapted Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, cinema itself was still finding its voice. The 1925 silent film, directed by Rupert Julian and starring Lon Chaney, became a cornerstone of the horror genre. It was ambitious, chaotic, and revolutionary: three directors cycled through the production, reshoots abounded, and the final cut premiered at the Astor Theatre in New York on September 6, 1925.

Chaney, known as the Man of a Thousand Faces, created his own makeup — inserting wires, cotton, and white paint to distort his nose and cheekbones. The studio kept his look secret until the premiere. When Christine unmasked him on screen, audiences screamed. Critics hailed the film’s technical mastery: elaborate sets that recreated the Opera Garnier in detail, daring camera work, and flashes of two-color Technicolor, a rare luxury for the era.

Even without spoken dialogue, The Phantom of the Opera resonated through its live orchestral accompaniment. It was more than a film — it was theatre reborn through light and shadow. And it introduced cinema’s first romantic monster, paving the way for Dracula, The Mummy, and every misunderstood creature that followed.

1986: The Musical That Never Died

In 1986, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber transformed the tale into a global phenomenon. Premiering at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London, the musical reframes Erik not as a fiend but as a tragic anti-hero — a brilliant, broken man whose love for Christine blurs devotion and obsession.

The show became the longest-running musical in Broadway history, with more than 13,000 performances and an estimated 150 million viewers worldwide. When Joel Schumacher adapted it for film in 2004, starring Gerard Butler and Emmy Rossum, reviews were divided, but Webber’s soaring score endured.

Earlier cinematic versions had each left a distinct mark — Claude Rains’s 1943 film favored lush Technicolor, Hammer’s 1962 production leaned into gothic horror, and Robert Englund’s 1989 take reveled in grotesque violence. Yet none have surpassed the haunting power of the 1925 original, whose silence still speaks louder than any orchestration.

A Century Later: The Echo Beneath the Stage

Now, in 2025, the film’s centennial invites audiences to descend once more into the Opera’s catacombs. Restored 4K editions tour silent-film festivals with live musical scores, reminding us how moving images once conquered hearts without words.

The Phantom endures because his story isn’t about fear of the other — it’s about the need to be seen. His mask hides not evil, but despair. That human ache is precisely what draws Guillermo del Toro to him.

Del Toro’s Signature: Souls Inside Monsters

Across Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water, and now Frankenstein (2025), del Toro has refined a signature both visual and spiritual: monsters who feel, humans who destroy. His worlds are liminal — perched between beauty and decay — where empathy becomes the only redemption.

Asked recently what he’d adapt next, del Toro admitted:

“I’d love to do The Phantom of the Opera… but I’d do it differently.”

It’s easy to imagine what that means. His Phantom wouldn’t be a villain in a mask but an artist imprisoned by the cruelty of perception, a reflection of how society fears what it cannot categorize. Much like Frankenstein’s Creature, he longs for connection, not pity — and finds only horror.

Why It Matters

Revisiting The Phantom of the Opera a century later isn’t just an act of nostalgia; it’s an acknowledgment that Erik’s song still echoes through time. Leroux wrote of a Paris haunted by progress and isolation; Rupert Julian filmed a silent scream of unrequited love; Webber turned that scream into melody.

Now, perhaps only Guillermo del Toro — the filmmaker who builds cathedrals from ruin and grace from deformity — can give the Phantom what he’s searched for since 1910: a soul that the world dares to love.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.