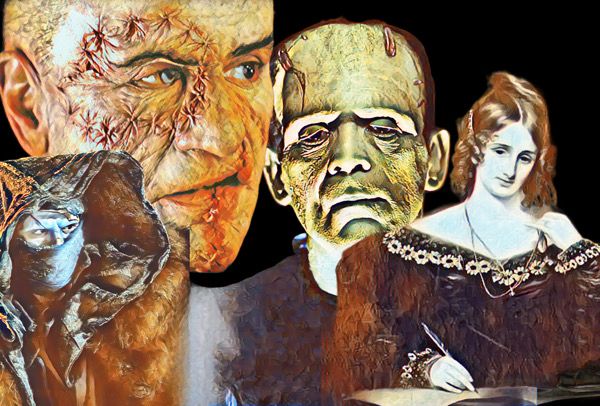

It’s striking how, more than two centuries after the publication of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley, we’re still circling the same moral dilemma that inspired the young English writer in 1818: what happens when a man creates something he cannot love? And in cinema, that question has been magnified by a lasting split — between the popular myth of the monster and the tragic humanity of its creator.

Most people don’t know Shelley’s Frankenstein; they know Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein. The 1931 Universal film, directed by James Whale, cemented the image of the creature with bolts in its neck, vacant eyes, and the immortal cry of “It’s alive!” It’s an iconic vision, yes — but far removed from the novel. Shelley’s monster is not mute, nor grotesque by design. Her story is about guilt, loneliness, and the unbearable cost of ambition — about the danger of playing God.

From that point forward, the myth split into two cinematic lineages: one of spectacle and one of soul. On one side, the expressionist horror born from Karloff’s image — gothic, visual, electric. On the other hand, the rarer attempts to return to Shelley’s text, with its moral philosophy, emotional intelligence, and human tragedy.

The very first film adaptation, produced by Edison Studios in 1910, was already a moral parable more than a horror story. In its brief, silent 13 minutes, the creature emerges from a cloud of smoke, born not of lightning but of alchemy — an experiment in vanity and remorse.

Decades later, Hammer Films offered its own reinvention with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. Though still rooted in gothic excess, it moved closer to Shelley’s core themes — scientific arrogance, moral decay, and the haunting absence of empathy.

But it was in the 1970s that American television came closest to Mary Shelley’s novel. Frankenstein: The True Story (1973), an NBC miniseries, is a gem often forgotten. It was the one that impressed me the most, featuring Leonard Whiting, fresh from Romeo and Juliet, as the scientist, a young Jane Seymour as Elizabeth, and Michael Sarrazin as the creature.

The Creature begins handsome and articulate, but gradually decays, making visible the moral corruption Shelley described. It is one of the few adaptations that truly understands the heart of the book — the fear of rejection and the longing for acceptance.

Just a year later, in 1974, came its most affectionate inversion: Mel Brooks’s Young Frankenstein. Shot in black and white, using the original Universal lab equipment, it’s a parody that plays like a love letter. Starring Gene Wilder, the film is both satire and homage — laughing at gothic clichés while revering their artistry. Beneath the jokes lies a genuine meditation on inheritance and identity: a grandson who tries to redeem his family name without repeating his ancestor’s mistakes. In Brooks’s hands, laughter becomes a kind of forgiveness — the redemption Shelley’s monster never found.

In 1994, Kenneth Branagh took on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with the explicit promise to adapt “the text, not the myth.” Produced by Francis Ford Coppola, the film set out to be definitive — literary, romantic, visceral. And in many ways, it is. Branagh reinstated Captain Walton’s letters, the Arctic framing, and the tragic grandeur of the prose. But the result drowned in its own theatricality. For all its ambition, the humanity Shelley wrote about was buried beneath operatic excess. Still, it remains the most faithful adaptation ever filmed, and what endures — achingly beautiful — is Patrick Doyle’s score, a symphonic act of empathy that finds the soul the film sometimes forgot.

Ten years later, Hallmark quietly released its own Frankenstein (2004), directed by Kevin Connor and starring Alec Newman and Luke Goss. Often overlooked, it’s one of the most textually faithful versions: it preserves the epistolary structure, the Arctic setting, and the creature’s eloquent monologues. Modest in scope, but deeply human in spirit.

More recent attempts, like Victor Frankenstein (2015) with James McAvoy and Daniel Radcliffe, reimagined the story through the eyes of Igor — a character who doesn’t even exist in the novel. Inventive, yes, but detached from Shelley’s essence.

And now, three decades after Branagh’s film, Guillermo del Toro revisits the myth. His Frankenstein (2025) marks the first major auteur-driven adaptation since the 1990s. Known for exploring the humanity within monsters (Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water), del Toro restores the story’s emotional and philosophical depth — a tale of empathy, solitude, and love misunderstood.

With Oscar Isaac, Jacob Elordi, Mia Goth, and Christoph Waltz in the cast, del Toro’s film reclaims Frankenstein as tragedy rather than terror — a meditation on creation, compassion, and the ache of being unwanted.

Between Shelley’s articulate creature and Karloff’s mute icon, there lies more than a century of struggle to reconcile the human and the monstrous. Perhaps only now, under del Toro’s hand, will that balance be achieved — the quiet compassion that Patrick Doyle’s music already intuited in 1994: the beauty that rises from ruin, and the impossible love between a creator and the life he abandoned.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.