Series bearing Harlan Coben’s signature tend to share certain traits: they are based on his best-selling novels, revolve around a central mystery, and surprise viewers with intricate twists and unexpected conclusions. Lazarus has one essential difference: it was written directly for Prime Video — in other words, it’s an original story.

The protagonist, Joel “Laz” Lazarus, is a forensic psychiatrist who returns to his hometown after the apparent suicide of his father, Dr. Jonathan Lazarus. Laz also carries an old wound: his twin sister, Sutton, was murdered about 25 years ago in an unsolved crime that marked him deeply. Upon his return, he begins to experience visions that challenge reality — “ghosts,” clues, and fragments that lead him to investigate not only his father’s death but also older cases that may be connected. Over the course of six episodes, Laz uncovers family secrets, the true scope of his father’s medical practice, the fates of missing or murdered patients — and how everything spirals back to the past. I’ll stop here before revealing (for now) who killed whom. Because in Lazarus, the journey matters more than the revelation.

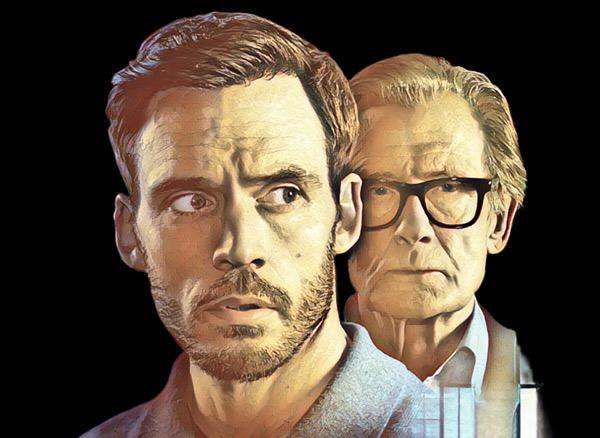

Starring the excellent Sam Claflin, the series opens with one of the most hauntingly beautiful songs ever written by Michel Legrand — “The Windmills of Your Mind”, the Oscar-winning theme from The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). The original French lyrics were by Eddy Marnay, but the English version shines with the brilliance of Alan and Marilyn Bergman. The song poetically explores the human mind, memory, time, and the sensation of being trapped in a continuous loop of thoughts and recollections.

It fits Lazarus perfectly because the series weaves two intertwined threads: intergenerational trauma and the rewriting of reality through memory and the supernatural. Joel’s return home isn’t just about his father’s death — it’s about confronting the night he tried to bury forever: Sutton’s murder. That key childhood moment becomes the epicenter of the entire story — guilt, silence, fragmented memories, and buried family truths. The father, once a figure of authority and healing, reveals himself as the opposite: a manipulative and destructive force.

The supernatural — the visions, ghosts, and recorded therapy sessions — works as a metaphor for the family unconscious that refuses to stay hidden. The apparitions aren’t just thriller gimmicks; they are manifestations of the past’s weight, of an inherited pain. Joel, a psychiatrist who treats disturbed minds, is unable to treat his own. This contradiction gives the story its depth: the healer who needs healing.

Jonathan Lazarus himself is a fascinating character — brilliant, cultured, enigmatic — and gradually unmasked as the architect of a network of deaths and deceptions. He embodies the patriarch who commits evil under the guise of science. Joel inherits the office, the files, the mask of “Dr. L,” and faces the crossroads: to repeat the legacy or to break it. The final scene suggests that even as he dismantles his father, he internalizes him. The line “Sons are like their fathers” tolls like a dark bell: legacy is not just a name — it’s trauma, tendency, and an invisible mold.

All the characters orbit the same nucleus, revealing that the “Lazarus family” is an ecosystem of wounds, secrets, and moral ambiguity. This web echoes classical psychoanalytic concepts: fate neurosis and psychic determinism. The first refers to the unconscious impulse to repeat painful experiences, as if trying to master what once dominated us. It isn’t destiny — it’s the unconscious replaying an unresolved trauma. The second asserts that nothing in mental life is accidental: every act, slip, or choice has a motive, even if it lies beneath awareness.

These concepts reverberate through Legrand’s opening song: the mind as a windmill, forever turning as the past tries to make sense of itself. Fate neurosis is that endless rotation; psychic determinism is the engine that drives it.

In Lazarus, Joel lives inside this very trap: he returns to the past, mirrors his father’s path, revisits his sister’s death — all propelled by the psychic force binding him to a family trauma. And the viewer is left not with an ending, but with a question: to break or to repeat? (Here’s the hint: through awareness, reflection, and analysis, yes — it is possible to break.)

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.