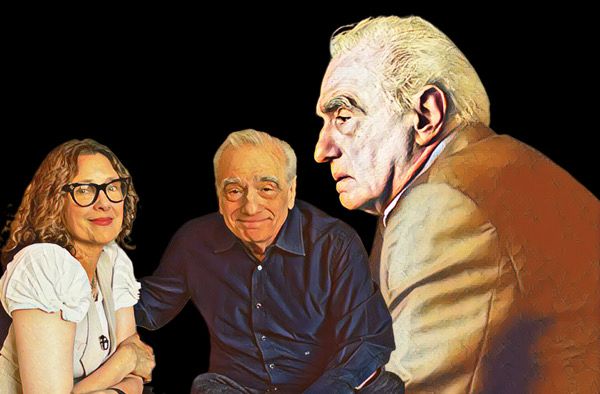

There’s a certain wisdom in the old saying that one should never meet their idols. Mr. Scorsese, Rebecca Miller’s five-part documentary series, proves that truth with elegance — and a bit of frustration. Martin Scorsese has long been “the director’s director,” the man who redefined American cinema, exploring faith, violence, guilt, and redemption like no other. Miller’s series promised to unveil the man behind the art — the genius, the historian, the restless seeker. But discovering who Scorsese really is isn’t quite what the series delivers.

The myth speaks — and dominates the frame

Scorsese has always been a born storyteller. His frenetic energy and encyclopedic recall make every anecdote a gift, and Miller wisely lets him talk. His voice, woven with an extraordinary archive of footage and film clips, is mesmerizing. On that level, Mr. Scorsese is a cinephile’s dream — a master class in his own words.

Yet there’s an inherent risk when the subject becomes his own narrator: the myth overpowers the man. The complexity of an artist fully aware of his genius — one who spent decades chasing recognition, oscillating between humility and hunger for the Oscar he so famously craved — remains largely unexamined. As The Guardian noted, the series “treats Scorsese as a secular saint — enlightened by his own work but rarely questioned by it.” Seeing one of cinema’s most celebrated voices still mourning his misunderstood youth or lamenting being “an outsider” feels oddly indulgent, even wearying.

What it shows — and what it shies away from

Miller’s scope is ambitious, but the depth is uneven. As The Washington Post observed, some films — Taxi Driver, The Last Temptation of Christ — receive rich context, while others (The Age of Innocence, Kundun, Silence) are treated almost in passing. The series hints at personal struggles — drug addiction, near-death moments, failed marriages, creative partnerships — but in frustratingly cursory strokes. His estrangement from De Niro, his later bond with DiCaprio, his complicated relationship with faith and fame: all are mentioned, rarely explored.

As IndieWire put it, Mr. Scorsese is “magnificent as compilation, mild as revelation.” It’s a treasure trove of imagery, but not of insight.

Rebecca Miller’s reverent eye

It’s not hard to understand Rebecca Miller’s approach. She wanted to avoid referencing the men whose names are linked to hers, yet she grew up surrounded by icons — the daughter of Arthur Miller and the wife of Daniel Day-Lewis — and carries within her a naturally respectful gaze toward monumental figures. She’s spent a lifetime among towering artists.

In interviews, she said her goal was to explore Scorsese’s inner conflict — his Catholic guilt versus his fascination with violence — but also admitted she “had no idea how enormous the task would be.” What emerges is a work made with deep affection, but little interrogation. As RogerEbert.com observed, “It’s a love letter, not a dissection.”

When love for cinema replaces human conflict

There are luminous moments — Scorsese reflecting on his childhood in Little Italy, the moral codes that shaped Mean Streets and Goodfellas, the way film became his faith. But when he turns inward, the tone flattens into self-mythology. He’s not wrestling with his past so much as narrating it. As AP News aptly put it, “Mr. Scorsese gives us Scorsese as the ultimate narrator of his own mythology — the director claiming the final cut of his life.”

Mr. Scorsese is rich, polished, and undeniably significant, but the series is too safe to deliver on its boldest promise. It’s a tribute to an extraordinary artist, not a revelation of the man. Miller offers Scorsese as he wishes to be seen: the chronicler of American dreams and sins, a visionary still haunted by his own exile.

Fascinating, yes. But one leaves wondering what truths might have emerged if someone else had held the camera — or dared to interrupt.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.