With the release of Nuremberg (2025), directed by James Vanderbilt and starring Rami Malek and Russell Crowe, it’s understandable that many viewers will confuse it with the legendary Judgment at Nuremberg (1961). The new film takes a different perspective — that of psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, assigned to assess the mental state of Nazi leaders, among them Hermann Göring. But Stanley Kramer’s Oscar-winning film doesn’t unfold behind the scenes. It takes place at the heart of the courtroom, where judges themselves stand accused of turning the law into an instrument of genocide. It’s a trial of conscience, not merely of men.

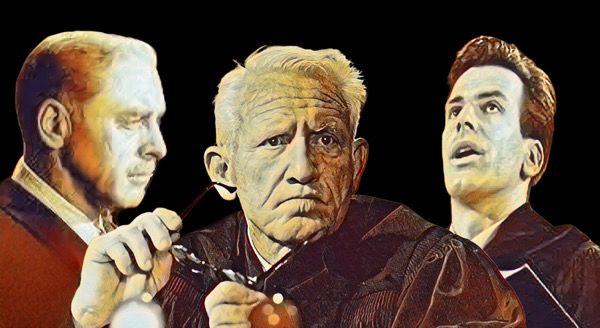

For me, Judgment at Nuremberg is one of the most relevant and masterfully made films ever produced. I’ve seen it countless times — and with each revisit, I find new layers, from the austerity of its direction to the humanity in its silences. It’s a courtroom epic of rare theatrical intensity: Spencer Tracy as Judge Dan Haywood, Burt Lancaster as Nazi magistrate Ernst Janning, Maximilian Schell as the defense attorney (in the performance that earned him an Oscar), Judy Garland and Montgomery Clift in deeply moving supporting roles, and Marlene Dietrich as the widow struggling to sustain Germany’s denial.

The final monologue, delivered by Tracy and shot in a single take, remains one of the most powerful moments in cinema history. When Janning insists he “didn’t know” what was happening, Haywood’s answer — “it came to that the first time you sentenced a man you knew was innocent” — becomes the film’s moral core. It’s a line that echoes far beyond World War II; it’s about every society that chooses not to see, out of convenience or fear.

I was fortunate enough to attend the Broadway revival decades later, with Maximilian Schell now playing Janning — no longer the defense attorney Hans Rolfe, but the guilty man himself. A perfect, almost symbolic circle: the actor who once argued for innocence now carried the weight of guilt. The text, born as a 1959 television play (Playhouse 90), returned to the stage with renewed force. It was a visceral experience — a moral tribunal brought to life before the audience.

Behind the scenes, the 1961 production is a story of artistic bravery and legendary craftsmanship. Kramer believed cinema could — and should — debate ethics. Working with a modest budget and a cast of stars who accepted symbolic salaries, the team reconstructed the trials with documentary precision. Abby Mann’s screenplay condensed sixteen defendants into four and drew inspiration from the Katzenberger Trial, a real case that led to the execution of a Jewish man accused of relations with an Aryan girl. The film’s “Feldenstein case” mirrors that story — a symbol of justice perverted.

Several details explain why the film feels so authentic. Montgomery Clift’s scenes were almost improvised; frail and struggling to remember his lines, he was encouraged by Kramer to let that nervousness become part of the character. It’s nearly impossible to keep a dry eye watching him. Judy Garland, returning to dramatic cinema after seven years, filmed her scenes in just eleven days, her vulnerability utterly real. Burt Lancaster spends half the film in silence before erupting into a ten-minute confession, also shot in a single take. And Marlene Dietrich, ever the perfectionist, demanded costumes by Jean Louis and complete control over her lighting in every shot.

The impact of the premiere was enormous. The world premiere took place in West Berlin in December 1961. Faced with real footage of concentration camps — shown unflinchingly in the courtroom — the German audience left in silence. No one knew how to applaud. It was a film impossible to watch “merely as entertainment.”

Even the final credits carry irony and lament: a note reminds viewers that none of the real defendants from the judges’ trial were still in prison when the film premiered — just as Hans Rolfe’s character had predicted. Judge Haywood’s response, therefore, gains even greater resonance: releasing them might be logical, he says, but “to be logical is not to be right — and nothing on God’s earth would make it right.” Kramer’s cinema knew how to turn discomfort into a political weapon.

It’s no wonder Judgment at Nuremberg was added to the U.S. National Film Registry in 2013. Its black-and-white cinematography reinforces the sense of moral confinement; the tight framing makes the audience feel the weight of the word “guilt.”

Decades later, Nuremberg (2025) returns to the same setting but replaces the courtroom with the psychiatrist’s office. If the new film tries to understand what goes on inside the mind of the perpetrator, the 1961 classic asks how the perpetrator was born from within the law. One examines the brain; the other, the moral spine. And that may be why Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg remains — and will remain — the definitive film on the subject. Because it isn’t about monsters. It’s about ordinary men who, out of fear or convenience, chose to obey.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.