In 1945, the world was trying to comprehend the incomprehensible. The end of World War II had exposed crimes of such magnitude that the very notion of humanity seemed shaken. It was in that moment that the Nuremberg Trials were born — the first international tribunal to hold a government’s leaders accountable for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

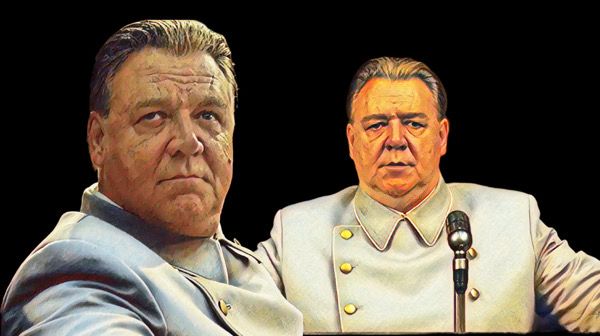

Among the defendants sat Hermann Göring, Reichsmarschall of the Luftwaffe, Hitler’s right-hand man, and one of the most powerful figures of the Third Reich. Charismatic, cunning, and disturbingly articulate, Göring embodied the Nazi elite that twisted power and law into instruments of annihilation.

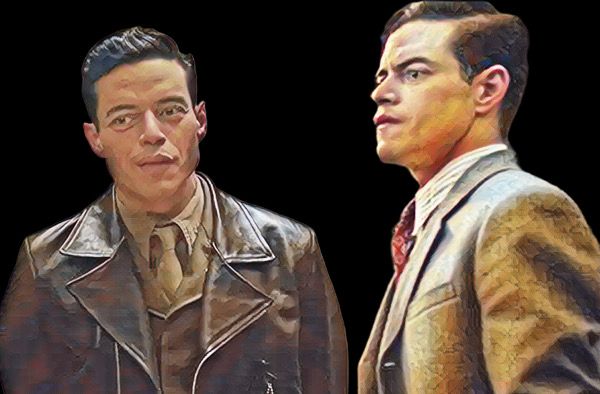

But Nuremberg (2025), directed by James Vanderbilt, does not follow the proceedings from the judges’ bench. Instead, it unfolds behind the courtroom, during the months when the accused awaited trial — focusing on the true story of Douglas Kelley, portrayed by Rami Malek, the American psychiatrist assigned to determine whether the Nazi leaders were mentally fit to stand trial.

Among all the prisoners, Göring (played magnificently by Russell Crowe) stood out. Intellectually superior, vain, and eerily composed, he became a psychological adversary for Kelley, who had to analyze his mind without being seduced by it. Based on Jack El-Hai’s book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, the film reconstructs the chilling game of manipulation and control that emerged between the two — a moral chess match in which the psychiatrist sought to understand how an educated, cultured, and rational man could become one of the architects of genocide.

This uneasy coexistence becomes the heart of the film: an intellectual and ethical duel where every question reverberates far beyond the prison walls. What is evil? Does it arise from madness, ideology, or obedience? And to what extent does trying to understand it risk being tainted by it?

Vanderbilt directs with restraint and precision, crafting tension not from spectacle but from silence — in the confined spaces, the symmetry of cells, and the quiet unease of a Germany rebuilding itself amid moral ruin. The supporting cast — Michael Shannon, John Slattery, Colin Hanks, Leo Woodall, Richard E. Grant, and Lotte Verbeek — reinforces the sense that the entire world was holding its breath, confronting its own reflection.

Be warned of a Historical Spoiler.

The true story’s final irony is devastating. In October 1946, Hermann Göring escaped the gallows just hours before his execution, taking his own life with a hidden cyanide capsule. Years later, in 1958, Douglas Kelley also committed suicide the same way, swallowing cyanide during a New Year’s Day family gathering. To many, that act symbolized how deeply his immersion in Nuremberg’s darkness had scarred him.

More than a historical drama, Nuremberg is a mirror of human fragility. The film reminds us that the 1945 trial was not only about the past — it was a warning for the future. When reason overtakes conscience, and logic replaces morality, evil disguises itself as order.

Revisiting this story in 2025 feels almost like a moral obligation. In a world once again polarized, where hate speech and denialism resurface with alarming ease, Nuremberg stands as a painful and essential reminder: barbarity never begins with monsters — it begins with men who believe they are right.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.