Mary Shelley was just nineteen when she wrote Frankenstein, a novel barely two hundred pages long (unless you count illustrated or annotated editions). The story of its creation is nearly as legendary as the creature itself. One stormy night in 1816, on the shores of Lake Geneva, Shelley — joined by her husband Percy, Lord Byron, and John Polidori — accepted a challenge to write a ghost story. From that gathering would emerge The Vampyre (Polidori’s precursor to Dracula) and Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, a tale that forever blurred the boundaries between science fiction, gothic horror, and philosophy.

First published anonymously in 1818, the novel fused romantic fascination with nature and the growing anxiety over scientific ambition. It questioned humanity’s arrogance before creation, the moral cost of knowledge, and society’s instinct to destroy what it doesn’t understand.

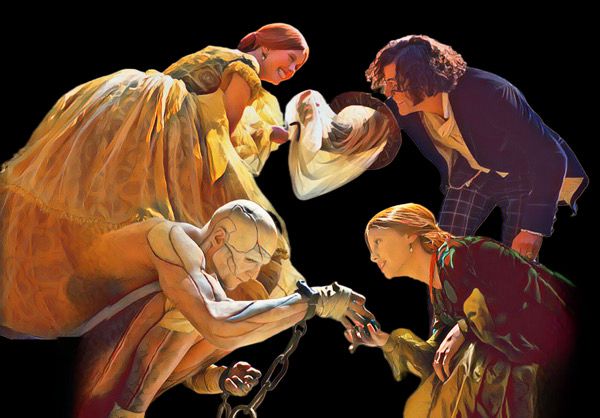

Cinema turned Frankenstein into a myth. Over a century of reinterpretations — from Boris Karloff’s pathos to Kenneth Branagh’s excess — have shaped our vision of the Monster. Guillermo del Toro’s adaptation, however, aims to be the definitive one. The Mexican auteur, long devoted to tragic monsters, brings to the story an aching tenderness. Casting Jacob Elordi as the Creature is a bold, almost subversive choice: his beauty becomes a mirror for our unease, while Oscar Isaac delivers a ferocious performance as Victor Frankenstein — not a visionary but a vain, envious man whose genius curdles into cruelty.

The story remains devastatingly simple: a scientist defies death, and by doing so, defies God. His creation is rejected, humiliated, and brutalized until it too becomes monstrous. For del Toro, as for Shelley, the true abomination is not the being assembled from corpses, but the man who refused to love it.

Structured in three acts that echo the novel, del Toro’s film trades grandeur for intimacy. Where Branagh saw tragedy in ambition, del Toro finds rot in arrogance. Isaac’s Frankenstein is not a fallen idealist but a man warped by trauma and pride — cold, self-absorbed, and godlike in his indifference.

Elordi’s Creature, by contrast, embodies the film’s fragile humanity. Like De Niro before him, he strives to give soul to a body that should not exist — and often succeeds. Yet the rubbery lilac makeup, more ethereal than frightening, is the weakest link in an otherwise breathtaking production. It lacks the rawness that could make his suffering tangible.

Mia Goth, always at ease in twisted romanticism, brings melancholy grace to Elizabeth, while David Bradley delivers the film’s most moving scenes as the blind man who teaches the Creature kindness — one of Shelley’s most luminous episodes.

Alexandre Desplat’s score is tender and mournful, carrying the emotional weight of doomed innocence. The production design and costumes are exquisite — painterly, gothic, and luminous, like a living Caspar David Friedrich canvas. Every shadow breathes. Every ruin whispers of regret.

Del Toro, undeniably “Team Creature,” restores the empathy Shelley intended. More than two centuries later, her warning about scientific overreach and moral detachment remains chillingly relevant. Frankenstein’s experiment gave life — and annihilated everything human around him. The devastation, del Toro reminds us, is eternal.

Guillermo del Toro turns pain into visual poetry. His Frankenstein is an elegy to human helplessness, divine arrogance, and the eternal search for redemption. A story that never dies.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.