Few true stories are as cinematic, absurd, and revealing as that of James A. Garfield, the 20th president of the United States, and Charles J. Guiteau, the man who killed him. An idealist and a fanatic, linked by chance and separated by destiny, their tragedy exposed the contradictions of a young nation trying to define democracy and decency.

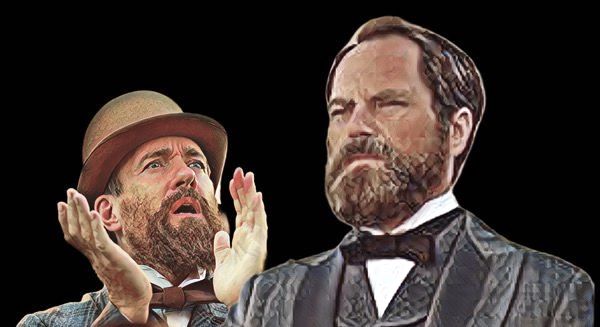

Netflix’s limited series Death by Lightning resurrects this forgotten episode with precision and modern urgency. Created by Mike Makowsky, directed by Matt Ross, and starring Michael Shannon and Matthew Macfadyen, it’s more than a period piece — it’s an autopsy of ambition, ego, and delusion, wrapped in velvet and blood.

The opening image — the assassin’s brain, suspended in glass

The series opens with what looks like fiction: a human brain floating in formaldehyde, labeled “Charles J. Guiteau,” sitting forgotten in a government warehouse. One worker asks: “Who the hell is that?” From that question, the story unfolds.

But the scene is true.

After Guiteau’s hanging on June 30, 1882, his body was dissected by doctors hoping to understand the mind of a murderer. His brain was removed, studied, and preserved, with parts sent to institutions like the Smithsonian and the National Museum of Health and Medicine, where fragments remain today.

At the time, scientists debated whether insanity could be physically “seen.” Some claimed Guiteau’s brain looked perfectly normal; others noted slight damage in the frontal lobe — the seat of judgment and empathy. Modern psychiatry would likely diagnose him with paranoid schizophrenia or a chronic delusional disorder, but in 1882, such language didn’t exist.

Makowsky uses that jarred brain as a haunting metaphor. Even dead, Guiteau became a curiosity — the ultimate American punishment: to be remembered only as an exhibit.

The man who believed in reform — and died for it

James Abram Garfield was born poor in a log cabin in Ohio in 1831. A self-taught scholar, preacher, and teacher, he fought for the Union during the Civil War — the side that opposed slavery — and rose to the rank of major general.

After the war, he served in Congress for nearly two decades, known for his intellect, integrity, and insistence that government should serve the people, not the powerful. When he was unexpectedly nominated at the 1880 Republican Convention — after giving a speech supporting someone else — he resisted. “This honor has not been sought,” he said. Yet the delegates demanded him.

When he took office in March 1881, America was still wounded from the Civil War. Garfield pushed for civil service reform, an end to the spoils system, and full civil rights for freed Black men and women. He wanted a nation governed by competence and morality, not by favors and factions.

“The president is a servant, not a king,” Shannon says of Garfield’s philosophy — and plays him that way: quiet, moral, sometimes awkward, but genuinely devoted to progress.

It’s that integrity that doomed him. In Washington’s swamp of patronage and resentment, Garfield was both too good and too naïve. And one man, burning with unmet ambition, mistook him for an obstacle placed by God.

The drifter who mistook rejection for destiny

Charles J. Guiteau, portrayed by Macfadyen with terrifying brilliance, is both tragic and monstrous. Born in Illinois to a fanatical father, he drifted from one failed identity to another — lawyer, preacher, writer, prophet — convinced each time that greatness was his birthright.

He even joined the Oneida Community, a utopian “free love” commune in upstate New York, where he was quickly expelled. The women nicknamed him “Charles Git-Out.”

By 1880, Guiteau had convinced himself that he had personally secured Garfield’s election by writing a campaign speech — one that no one had actually used. He began stalking the president, demanding a diplomatic post in Paris. When he was rejected, he declared that God commanded him to remove Garfield for the good of the nation.

Macfadyen plays him as an American Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro’s delusional fan in The King of Comedy): a man so desperate for validation that he’d rather be infamous than invisible. His performance is grotesquely magnetic — his American accent flawless, his mania almost tender.

The shooting — and the second bullet, fired by ignorance

On July 2, 1881, at Washington’s Baltimore & Potomac train station, Guiteau fired two bullets into Garfield’s back. Neither struck vital organs. He should have survived.

But 19th-century medicine killed him.

Doctors, rejecting the new theory of germs, probed his wound with unsterilized fingers and instruments. Dr. Charles Purvis, a young Black physician trained in antiseptic techniques, warned against it. His superior, Dr. Willard Bliss, waved him off: “I don’t believe in invisible monsters.”

Garfield endured 79 days of agony before dying of infection. His body became a battlefield between science and superstition — a literal fight over cleanliness and arrogance.

As Makowsky puts it,

“Guiteau fired the gun, but medicine finished the job.”

A mirror of two Americas

Garfield and Guiteau are opposites — and reflections. One believes in service; the other, in self. One embodies reason; the other, resentment.

Michael Shannon plays Garfield as the quiet conscience of a divided nation — a man whose nobility lies not in charisma but in clarity. He’s weary, idealistic, and human.

Matthew Macfadyen, by contrast, is chaos incarnate: a man intoxicated by his own importance. His Guiteau is grotesque, almost comic, until he becomes terrifying. When he begs Garfield — “Help me be great like you” — and bursts into tears, it’s both absurd and heartbreaking.

The actors’ chemistry is extraordinary. Macfadyen reportedly cried for real during that scene, overwhelmed by Shannon’s gravity. Their dynamic — faith versus delusion — becomes the emotional axis of the series.

What became of Guiteau

Guiteau was hanged in 1882, in front of a fascinated public. Ever the showman, he recited a poem (“I am Going to the Lordy”) and smiled as the trap opened.

His brain was removed for study; his skeleton was used in anatomy classes. To this day, parts of his brain remain preserved in medical museums — a literal relic of fanaticism.

The series closes the circle with this image. In its final episode, Lucretia Garfield (Betty Gilpin) visits the imprisoned Guiteau and tells him the only thing he cannot bear to hear:

“Your name will mean nothing.”

And then we return to that jarred brain — silent, suspended — proof that his legacy is nothing but curiosity, while Garfield’s humanity endures in memory.

The woman history tried to erase

Lucretia “Crete” Garfield, played with luminous restraint by Betty Gilpin, anchors the story. Intelligent, political, and deeply moral, she was far more than a grieving widow. Makowsky calls her “the quiet hero” — a woman confined by the expectations of 1881, but capable of vision far beyond them.

In the final scene, she sits at the table her husband built, surrounded by her children, staring at his empty chair — the heart of the American dream and the silence that follows its collapse.

The legacy that almost vanished

Garfield’s presidency lasted only four months, but its repercussions shaped modern American government. After his death, Vice President Chester A. Arthur, once a product of corruption, surprised everyone by embracing Garfield’s ideals. He signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which created the merit-based system that still governs U.S. public service today.

Arthur’s transformation — from political crony to reformer — is one of history’s quiet miracles. It’s also Garfield’s final victory.

Garfield himself was a man of astonishing intellect: a classicist who could write in Latin and Greek simultaneously with both hands, a teacher who believed education was the soul of democracy. Yet history largely forgot him. Lincoln and Kennedy became legends; Garfield became a footnote.

Death by Lightning restores his humanity, showing not just how he died, but why his death mattered — and how his ideas still pulse beneath the nation’s contradictions.

Memory, madness, and the echo of thunder

The final images of the series — the jarred brain and the empty chair — encapsulate America’s twin obsessions: the glorification of madness and the neglect of virtue.

Garfield believed in science, empathy, and the collective good. Guiteau believed the world owed him divinity. Between them lies the story of a nation that often confuses ego with destiny.

As Shannon said in interviews,

“This country is not well. The United States needs therapy.”

More than a century later, his words — and Garfield’s fate — still resonate.

Because what kills us, as Death by Lightning reminds us, isn’t always the bullet.

It’s the arrogance that rejects truth, the ignorance that denies science, and the vanity that mistakes attention for meaning.

And against that — even now — no one is safe from the lightning.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.