Guillermo del Toro has always understood horror as a mirror to the unconscious. In Frankenstein, he turns Mary Shelley’s myth into a profoundly psychoanalytic experience — an elegy about abandonment, loss, and guilt. If Shelley’s novel hinted at the unconscious, Del Toro, instead, dives into it completely. Nothing is literal; everything is symbolic. At its heart is Victor Frankenstein — the son who never overcame his mother’s death, the man who tried to become God to defeat death, and ended up destroyed by his own creation.

Freud’s Oedipus complex defines the human struggle: the son’s unconscious desire for the mother and rivalry with the father. Del Toro translates it into image and emotion. Victor worships his mother with religious devotion and resents his cold father. His grief becomes repression — the drive to recreate what was lost. Science becomes the disguise for symbolic incest. By giving life to the creature, Victor tries to become the mother, the source, the womb. He doesn’t just want to conquer death; he wants to possess life.

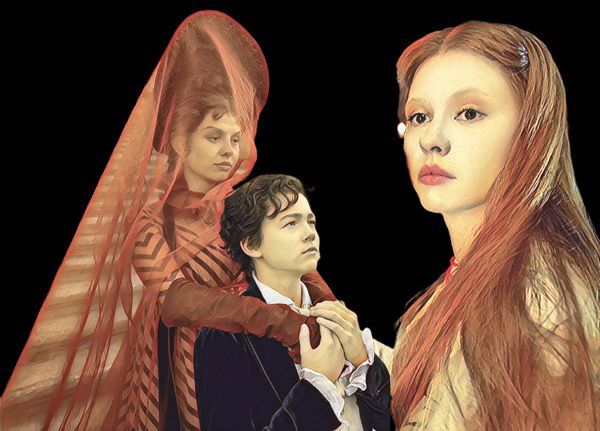

Casting Mia Goth as both mother and fiancée is the film’s Freudian masterstroke. Elizabeth is the return of the repressed — the forbidden desire disguised as love. The woman Victor loves bears the face of the mother he lost. The circle closes: displaced love, repetition, destruction. Freud called it the repetition compulsion.

The father stands as the law, the authority, the God who forbids. The creature is the return of guilt — Victor’s doppelgänger, his shadow.

“I pursued nature to her hiding places.” — Victor describes his quest as an erotic violation of the feminine — Nature as the Mother to be conquered.

Color, Cross, Gloves, and Desire

Del Toro reinforces it all visually.

Red is desire, blood, and life — Eros itself. The mother wears red: passion, womb, transgression.

Green belongs to Elizabeth — rebirth, purity, illusion. She is the Anima, the ideal feminine. When Elizabeth appears under her red umbrella in the rain, pure love turns carnal — red invades green, and tragedy is sealed.

The cross necklace, shining over Victor’s chest, is the symbol of guilt and divine prohibition — the Father watching. Religion becomes a substitute for repressed desire: a sacred attempt to cleanse sin. The cross gleams when lightning strikes, turning faith into judgment.

Then come the red gloves — the forbidden touch. They are repression made visible, the erotic impulse covered by a moral shield. Victor wears them to separate science from flesh, to create without touching. Yet the color betrays him. When he finally touches the creature, the gloves blaze crimson — passion breaking through guilt.

Together, these elements — red (mother/desire), green (lover/ideal), gold (faith/guilt), and crimson gloves (repression/eroticism) — form the visual psyche of Frankenstein.

Phallic Symbolism: Power, Creation, and the Forbidden

The laboratory’s towering antenna is pure phallic imagery — a steel monument of rebellion, the son’s attempt to seize the father’s power. It channels divine energy, penetrates the heavens, and awakens the dead. Freud would call it the fulfillment of the infantile fantasy: possessing the father’s potency.

Jung would see unbalanced masculine energy — creativity turned destructive. Lightning, thunder, flesh convulsing — it’s an erotic ritual of sin and creation. The lab becomes a temple of guilt, where science, faith, and desire fuse.

Del Toro paints Shelley’s myth with the colors and symbols of the psyche: red for passion, green for illusion, gold for guilt, steel for hubris. The result is a visual confession — a gothic cathedral of the unconscious, where every color and shape exposes a secret of the soul.

“I had desired it with an ardour that far exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.” — Desire fulfilled gives way to disgust; the pleasure of creation is immediately punished by guilt.

Aesthetically, Del Toro’s Frankenstein breathes sensuality even in death. Every gesture, every look between Victor and his creation is charged with longing. It’s a dialogue between Eros and Thanatos — desire and destruction. Freud believed every creative act was an act of sublimation — libido transformed into art, science, or myth. In Frankenstein, every touch and every glance between creator and creature is soaked in unspoken desire. Love and disgust coexist; affection and fear collapse into one another. The film becomes a confession of the unconscious — a love story between the creator and the reflection of his own repression.

But Del Toro doesn’t stop at Freud. His film also thrives in Jungian territory, expanding the myth into the realm of archetypes. In Carl Jung’s psychology, the creature is the Shadow — everything within ourselves that we reject and project outward. Victor, obsessed with perfection and reason, denies instinct, flesh, and failure. The creature embodies precisely that: the banished, unintegrated part of his psyche. Meanwhile, the mother/Elizabeth duality — both played by Mia Goth — represents the Anima, the internal feminine principle Victor tries to dominate but never assimilates. In loving her, creating her, and losing her, he fails to reconcile emotion and reason, life and death. Jung would say he fails the process of individuation — he cannot unite the opposites that define him.

The father, through the Jungian lens, becomes the Senex — the wise old man turned tyrant, the archetype that must be overcome. The laboratory, drenched in light and shadow, is the physical space of the unconscious. The act of creation is a symbolic attempt to unite the Shadow and the Anima, the first step toward psychological wholeness. But Victor fails — unable to face his own reflection, he collapses. His creation is the wound made flesh.

By fusing these elements — Prometheus’ defiance, Oedipus’ tragedy, Jung’s descent into the self — Del Toro transforms Frankenstein into a meditation on the human mind. Freud and Jung coexist here: Eros and Thanatos, love and destruction, sublimation and collapse. The horror is not the monster, but the recognition: that we all carry within us a Victor and a creature, a father and a mother, a love entwined with guilt.

Del Toro understands what Freud intuited — that the deepest terror is the longing for the impossible: the return to the womb, the reunion with what created us. Frankenstein, in his hands, ceases to be a story about science and becomes a confession of the soul. A son who tried to replace the mother, challenge the father, and in doing so, unleashed his own shadow.

When Mia Goth appears — sometimes as mother, sometimes as bride — she is not two women but one: the embodiment of the love Victor can neither name nor escape. Del Toro turns Shelley’s myth into a Freudian dream filmed as gothic poetry, where beauty and horror are indistinguishable. In the end, Frankenstein is about the man who tried to be God — and found only the mirror of his own unconscious.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu