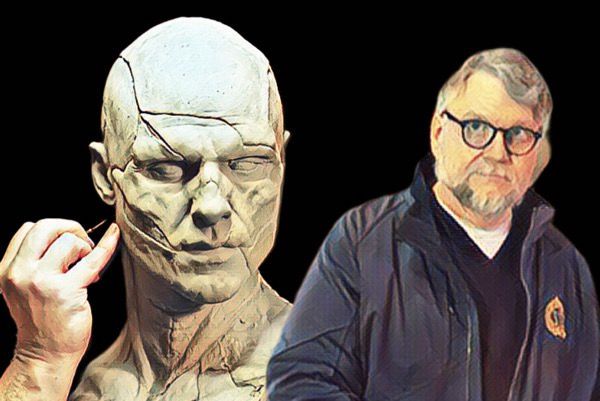

When Mary Shelley published Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus in 1818, she could never have imagined that, more than two centuries later, her monster would still be walking among us. The novel, written when she was only 19, was born out of both fear and curiosity: how far could man go in his desire to create, to control, to play God? Guillermo del Toro, who had dreamed of making this film for decades, seems to have found an answer — or at least an echo of one — in his 2025 adaptation.

The Mexican director, who has always given voice and soul to outcasts and creatures, delivers here his most intimate and moving work. What Shelley conceived as a philosophical horror novel, Del Toro turns into a visual elegy — a story about guilt, fatherhood, and forgiveness. The power of the film lies precisely in the space between the page and the screen, between the 19th century and the 21st.

A New Frame for the Same Pain

Shelley’s novel opens with a series of letters written by Robert Walton, an Arctic explorer who rescues a man adrift on the ice: Victor Frankenstein. This “story within a story” adds distance and ambiguity to the narrative, as if the horror were already part of memory.

Del Toro keeps this structure but turns it into a cinematic device — a ship trapped in the ice, a man chasing another to the ends of the earth, and the echo of an unburied guilt. The opening (and closing) of the film feels like a confession: creator and creature locked in the same frozen circle of obsession and remorse.

Childhood, Trauma, and the Original Wound

In Shelley’s book, Victor Frankenstein is born into a loving, privileged family. His downfall comes from unbridled scientific ambition. In Del Toro’s version, that ambition is replaced by emotional damage: the loss of his mother at birth, the cruelty of his father, the favoritism toward his brother William.

It may seem like a small change, but it shifts the entire story. Shelley wrote during the Enlightenment, when the fear was science itself. Del Toro films in an age haunted by emotional inheritance. His Victor doesn’t seek creation out of pride, but out of loneliness. The monster isn’t born from arrogance — it’s born from longing.

The Creature: From Vengeance to Compassion

In the novel, the creature is the purest mirror of humanity — articulate, intelligent, and desperately alone. When rejected by its maker, it becomes a symbol of how cruelty is born from exclusion. “I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel,” it tells Victor — one of literature’s most haunting lines.

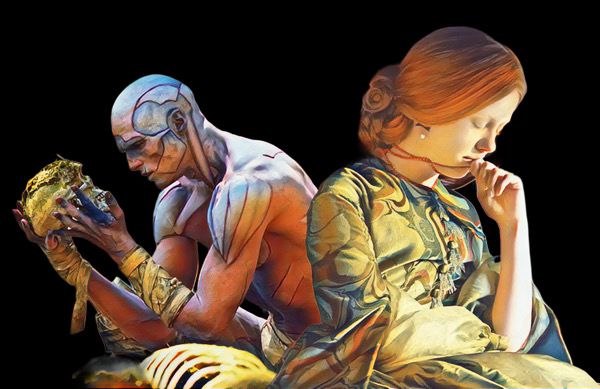

Del Toro keeps that essence but rewrites the destiny. His creature, played by Jacob Elordi, is less wrathful and more tragic. Instead of revenge, it seeks connection. The film humanizes it so deeply that horror turns into empathy. There’s rage, yes, but also tenderness — something Shelley’s younger self, still mourning her own losses, could not yet offer her monster.

The Impossible Love and the Silenced Woman

In Shelley’s version, Elizabeth Lavenza is Victor’s gentle fiancée — a figure of innocence who becomes a casualty of his sins. Her death seals his punishment. In Del Toro’s adaptation, Elizabeth is engaged to William, Victor’s brother, shifting the triangle and replacing romance with jealousy and guilt. She’s no longer a passive symbol of purity; she becomes an observer of decay, a woman who sees through the family’s rot.

That change resonates with Del Toro’s worldview: horror doesn’t only dwell in what is created, but in what is inherited. Elizabeth stands as witness — not merely victim — of the Frankenstein curse.

The Father, the Son, and the Broken Mirror

The father figure — absent, abusive, or both — has always haunted Del Toro’s cinema, and Frankenstein is no exception. Here, Leopold Frankenstein is a tyrant, incapable of love, shaping Victor’s fear of intimacy and obsession with control. The act of creation becomes an inverted act of love — one born out of pain.

The creature, then, is not a monster but a child — a reflection of a man who never learned tenderness. When they finally face each other (minor spoiler), the confrontation is not about destruction but forgiveness. It’s one of the most striking scenes in the film: the moment the monster looks at his maker and sees himself.

Science, Sin, and the Weight of Guilt

In Shelley’s text, the transgression is scientific: man dares to usurp the laws of nature. In Del Toro’s reading, the sin is emotional — denying grief, refusing love, trying to master what should be felt.

The film’s timeless setting, hovering between the late 18th century and a dreamlike Victorian world, reinforces that universality. Frankenstein could happen anywhere, at any time — which is precisely Del Toro’s point: the monster is not in the lab, it’s in the human heart.

The Ending: From Darkness to Light

In the novel, the creature vows to burn itself after Victor’s death — an ambiguous suicide, an ending without grace. Del Toro, instead, offers an epilogue of quiet redemption. His creature doesn’t perish; it departs. The farewell feels less like punishment, more like release — a final act of love between two beings forever bound by pain.

It’s the difference between Shelley’s Romantic despair and Del Toro’s humanist hope. The 19th century saw damnation as inevitable; the 21st century still believes in healing.

The Visual Language of Grief

Visually, Frankenstein (2025) is breathtaking. Shot across Scotland, England, and Canada, it trades the gothic laboratory for real architecture — the damp stones of Edinburgh, the vast corridors of Dunecht House, the frozen expanse of North Bay. The palette is all ash and silver, the light pale as regret.

Del Toro achieves what Shelley did with prose: he gives texture to sorrow. His images don’t imitate earlier cinematic versions — they reclaim them. Jacob Elordi’s creature is both terrifying and beautiful; Oscar Isaac’s Victor, haunted and exhausted, wears divinity like a curse.

Monsters That Cry

More than an adaptation, Del Toro’s Frankenstein feels like a confession. Like Shelley, he writes with pain — but where she destroyed, he seeks to heal. His film is about fathers and sons, creation and abandonment, love and fear.

The creature, in the end, is all of us: built from fragments, yearning to be seen without revulsion.

What the New Frankenstein Says About Us

By reimagining an 1818 myth, Del Toro does what great artists do — he turns the past into a mirror for the present. Shelley’s Frankenstein was born from the terror of science and the loneliness of the genius. Del Toro’s version emerges from the terror of disconnection — of losing empathy, of forgetting how to love, of failing to see ourselves in others.

Shelley created a monster to question creation. Del Toro recreates it to remind us of compassion. Two centuries later, perhaps that’s what we needed to hear most: that even the most broken creatures still deserve a second chance at light.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.