Eighty-five years ago, Walt Disney dared to dream of a film that would unite what seemed impossible: the abstraction of classical music and the magic of animation. Released on November 13, 1940, Fantasia was more than a feature — it was an artistic experience without precedent, a visual manifesto proving that art could transcend form. Conceived in 1938, when The Sorcerer’s Apprentice was already well underway — a luxurious “Silly Symphony” meant to revive Mickey Mouse’s popularity — the project grew when the short’s budget skyrocketed. If it was going to be expensive, it should also be magnificent. Disney decided to build eight animated segments set to classical works, with Leopold Stokowski conducting, Deems Taylor as live-action host, story direction by Joe Grant and Dick Huemer, and production supervision by Ben Sharpsteen.

The ambition wasn’t only artistic — it was technological. Recorded in multiple audio channels and presented through the pioneering Fantasound system (developed with RCA), Fantasia became the first commercial film shown in stereo, a precursor to surround sound. Walt wanted audiences to “hear images and see music.” This drawn symphony debuted as a roadshow — exclusive gala screenings with printed programs — in 13 U.S. cities, beginning at New York’s Broadway Theatre on November 13, 1940. Critics hailed it as revolutionary, but World War II, high production costs, and the expense of installing Fantasound limited its reach. Financial success came later, through decades of re-releases, restorations, and reappraisals. Today, Fantasia is preserved by the Library of Congress in the National Film Registry as “culturally and aesthetically significant.” The American Film Institute ranked it among the greatest animated films ever made — and it remains in that pantheon.

Structurally, Fantasia opens with an orchestra bathed in shadow and light as Deems Taylor introduces the concept — a visual concert. Each segment that follows feels like a new artistic language. In “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” (Bach), abstract forms take flight. In “The Nutcracker Suite” (Tchaikovsky), fairies, flowers, mushrooms, and fish dance through the seasons. “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” (Dukas) turns Mickey into the eager pupil whose magic spirals out of control. “The Rite of Spring” (Stravinsky) depicts Earth’s creation and the age of dinosaurs. The intermission playfully personifies the soundtrack itself. “The Pastoral Symphony” (Beethoven) conjures a mythological Arcadia of centaurs and cupids before Zeus interrupts their revelry. “Dance of the Hours” (Ponchielli) becomes a comic ballet in four acts. And finally, “Night on Bald Mountain” (Mussorgsky) gives way to “Ave Maria” (Schubert), transforming infernal chaos into a spiritual dawn.

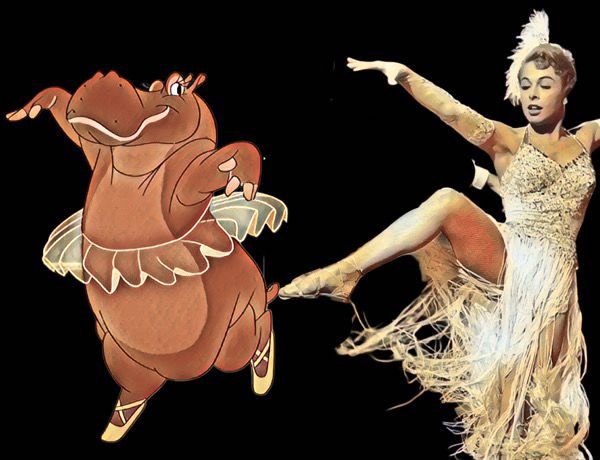

Among them, one sequence stands out as Fantasia’s beating heart — “Dance of the Hours.” Ponchielli’s ballet becomes both parody and homage, performed by ostriches (morning), hippos (afternoon), elephants (evening), and alligators (night). The sublime and the absurd meet in perfect rhythm. The prima ballerina Hyacinth Hippo pirouettes in pink tulle; Ben Ali Gator becomes her reptilian suitor; and Madame Upanova opens the day with diva flair. It ends in joyous collapse — chandeliers crashing, curtains tearing, the palace falling — a finale of comic grace rather than destruction.

That sequence’s charm was literally born from a dancer’s body. Marge Champion — a Hollywood prodigy trained in ballet from age three by her father, who had also coached Shirley Temple and Cyd Charisse — was the live-action model for three Disney heroines: Snow White (1937), the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio (1940), and here, the hippo ballerina. At 14, she was already filming movement references for animators, repeating pirouettes and pliés for hours so they could translate real weight and rhythm into “impossible” bodies. The joke works because the movement is true. Behind the tutu lies precision — the grace of a dancer who understood humor and elegance as part of the same motion. Marge lived to be 101 (passing in 2020), danced professionally until 82, and took classes until her nineties. She was a princess, a fairy, and a hippo — and in all forms, she danced.

Behind the scenes, Fantasia was a vast experiment. Disney’s team pushed the boundaries of technology with a seven-plane multiplane camera, intricate color-keying for every shot, live-action choreography, and even stop-motion snowflakes. Animators studied real dancers, watched the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and tested abstract compositions with artist Oskar Fischinger (whose collaboration ended over creative clashes). The final “Ave Maria” sequence remains a marvel: a continuous tracking shot that required days of filming and a custom-built horizontal camera crane moving across enormous glass panels. The shot almost failed after an earthquake shook the set — but it was finished, and the serenity that closes the film feels almost miraculous.

The exhibition history of Fantasia mirrors cinema’s evolution itself — from its 13-city Fantasound roadshow to mono and simulated-stereo reissues, the 1990 full restoration that reinstated Stokowski’s original mix, and the digital remasters of the 2000s that recreated its roadshow experience. Beyond the screen, the film became a franchise: concerts, theme park attractions, video games, and a thoughtful sequel, Fantasia 2000. Adjusted for inflation, Fantasia remains among the most successful films in U.S. box office history — but far more significant is its artistic legacy. It continues to shape music videos, experimental animation, and visual design, teaching generations that color, rhythm, and silence are storytelling tools.

Revisiting Fantasia today means returning to the roots of animation as art. In 1940, Disney believed audiences would embrace a sensory and intellectual experience at once. That optimism — equal parts naïveté and genius — paved the way for everything from cinematic musical storytelling to immersive sound design. And in the end, among gods, demons, and cosmic birth, the image that endures is that of a hippo in a tutu dancing to Ponchielli — a reminder that humor and grace can coexist, and that beauty often waltzes on the edge of the absurd.

Walt Disney himself understood that Fantasia was not a film but an idea. “Fantasia is timeless. It may run 10, 20 or 30 years. It may run after I’m gone.” He was right. You can’t remake Fantasia — you can only expand its dream.

In the 1980s, long before the age of remakes, Disney veterans Wolfgang Reitherman and Mel Shaw conceived “Musicana”, a spiritual successor mixing jazz, classical music, and myths. Planned sequences included a duel between a god of ice and a sun goddess set to Sibelius, scenes in the Andes with songs by Yma Sumac, animated caricatures of Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald, and a retelling of The Emperor’s Nightingale starring Mickey. The project was shelved, but its spirit lingered.

It was Roy E. Disney, Walt’s nephew, who resurrected the dream with Fantasia 2000, produced in the 1990s with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under James Levine. The sequel featured seven new musical stories and preserved The Sorcerer’s Apprentice as its bridge to the past. Premiering at Carnegie Hall before a global tour and an IMAX run, it brought Fantasia’s philosophy into the new millennium — an ode to the visual music Walt imagined.

A third film, “Fantasia 2006,” began early development in the 2000s with segments like The Little Matchgirl (Roger Allers), Lorenzo (Mike Gabriel), One by One (Pixote Hunt), and Destino — the long-lost collaboration between Walt Disney and Salvador Dalí, finally completed in 2003. The project was cancelled, but its individual shorts stand as spiritual successors, preserving the experiment’s heartbeat.

The legacy extends far beyond film. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice inspired a 2010 live-action blockbuster produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, and The Nutcracker Suite partly inspired The Nutcracker and the Four Realms (2018). There were even attempts — later abandoned — to adapt Night on Bald Mountain into a dark fantasy feature. Yet the truest descendants live in other forms: Fantasmic!, the nighttime water and fireworks show where Mickey conjures magic and battles Disney villains; the Fantasia Gardens mini-golf course in Orlando; and the iconic Sorcerer’s Hat, once the emblem of Disney’s Hollywood Studios.

Video games carried Fantasia’s spirit forward, too — from Atari’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1983) to the musical motion game Fantasia: Music Evolved (Harmonix, 2014), and Kingdom Hearts, where Yen Sid and Chernabog still reign as figures of myth. The symphony even returned to the stage through Disney Fantasia: Live in Concert, a breathtaking fusion of live orchestra and high-definition animation that continues to tour worldwide.

Eighty-five years later, Fantasia feels as alive as ever — a timeless act of creative faith. It reminds us that music and image are twin languages of emotion, and when united with imagination, they transcend time. The maestro is gone, but the orchestra still plays. And somewhere, Mickey still lifts his water bucket — dreaming that for one magical moment, we can all command the music.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.