Among the many figures in the history of art who seem larger than time itself, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is one of them. And thanks to the enduring popularity of her work, Frankenstein, she remains — even in the twenty-first century — a woman who continues to fascinate and intrigue.

The daughter of two radical thinkers — the feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft and the political writer William Godwin — Mary was born in 1797, into a world that hardly knew what to do with intelligent, free women aware of their own voices. From an early age, she lived under the weight of a name and the absence of a mother, yet built her own legacy by writing a groundbreaking work at just eighteen. Frankenstein stands as one of the most symbolic, modern, and visionary narratives in all of literature.

It was in 1816, during a stormy summer in Geneva, surrounded by Percy, Lord Byron, and John Polidori, that Mary conceived the story that would change everything. In the midst of a wager to see who could write the best ghost story, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, was born. It was not merely the tale of a scientist who creates life, but a metaphor for responsibility, solitude, and creation — for what it means to be human. Mary projected onto Victor Frankenstein the ambition and blindness of men, and onto his Creature, the exclusion and abandonment she herself had known. It was also a woman’s cry in a world that refused to listen.

Published anonymously in 1818, the novel was for many attributed to Percy Shelley. Only later would Mary be recognized as its true author. That revelation not only reclaimed her voice but redefined the very notion of female authorship in the nineteenth century. Her courage to imagine the impossible — and to question male power over creation, whether of life or art — made her a forerunner of science fiction and one of the most important writers in history.

But Mary Shelley was not only the creator of Frankenstein. She was a woman who survived everything: loss, poverty, criticism, and erasure. After Percy died in 1822, she lived in mourning for years, yet kept writing. In The Last Man (1826), she foresaw a future devastated by plagues, solitude, and technology — centuries before the dystopian genre existed. Her gaze upon humanity was at once poetic and prophetic.

When she died in 1851, at the age of fifty-three, Mary left behind a legacy that still resonates today: the fusion of emotion and intellect, creation and destruction, body and mind. In her journal, she wrote, “I write to give shape to the chaos of my heart.” And the world continues to read that chaos as a mirror.

The Film That Reimagined Her: Mary Shelley (2017)

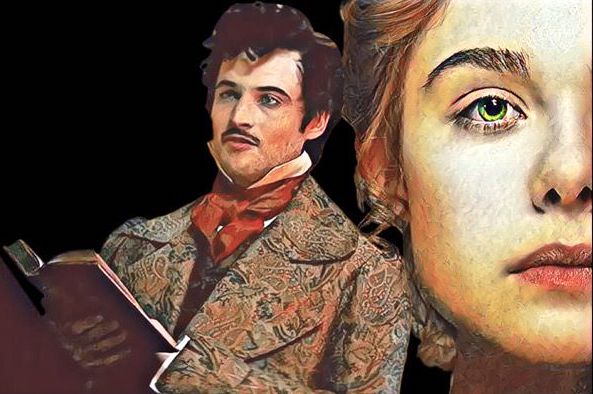

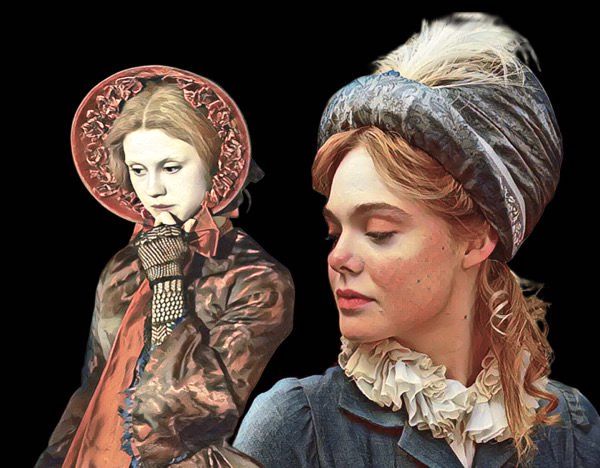

Directed by Saudi filmmaker Haifaa al-Mansour and starring Elle Fanning, Mary Shelley (2017) seeks to decipher both the myth and the woman behind the book. It is not a rigid biographical portrait, but a visual, poetic, and melancholic interpretation of a young woman who dared to defy time itself. Haifaa, one of the first female directors from Saudi Arabia, saw in Mary not only the writer but the very metaphor of female creation — a theme that runs throughout her own filmography.

The film follows Mary from adolescence through her conflicted relationship with her father and her consuming love for Percy Shelley (played by Douglas Booth). The production succeeds in capturing the Gothic and Romantic spirit of the era, with delicate costumes, a somber atmosphere, and the constant tension between freedom and repression. Elle Fanning plays Mary with a blend of fragility and strength, portraying her not as a martyr but as a creator — someone who confronts her own shadow to write what she feels.

Though it received criticism for softening historical details and simplifying complex characters, the film achieves something essential: it restores to Mary the authorship of her own creation. The birth of Frankenstein appears on screen as the catharsis of a woman who had seen death up close and transformed grief into art. It is no coincidence that the film’s closing line — “The story of Mary Shelley is a story of survival” — echoes as both an epitaph and a celebration.

Mary Shelley is not merely a biopic; it is a tribute. It is the gaze of a woman filmmaker upon another woman who dared to create the unimaginable — a reminder that there is something divine, and something monstrous, in every act of creation.

The Heart of the Monster

More than two centuries later, Frankenstein still beats with life. Every new reading reveals that the creature is, in truth, the mirror of its creator. Mary Shelley wrote about the pain of a rejected being, but also about the courage of a woman who, in the strict confines of the Victorian era, dared to invent her own destiny.

Her creature lived. And as Byron — friend, reflection, and ghost — once wrote, “The heart will break, yet brokenly live on.”

Mary Shelley is living proof of it.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.