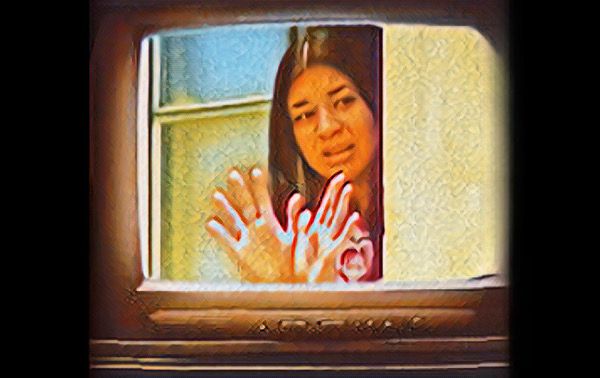

Brazil has joined the global true crime wave — a genre that transforms tragedy into storytelling, trauma into content. Netflix’s Caso Eloá – Refém ao Vivo (The Eloá Case – Hostage Live) follows that trend, reopening one of the country’s most devastating crimes: the kidnapping and murder of Eloá Cristina Pimentel, a 15-year-old girl whose final moments were broadcast live on national television.

In October 2008, the entire country stopped to watch what would become Brazil’s most infamous hostage crisis. Eloá was a bright, popular teenager living in Santo André, a middle-class suburb of São Paulo. Her ex-boyfriend, Lindemberg Fernandes Alves, was 22, seven years older, jealous, and violent. Their relationship had begun when Eloá was only 12, and after multiple break-ups and threats, she finally ended things for good. But he refused to let go.

On October 13, 2008, Lindemberg invaded the apartment where Eloá and three friends were studying for a school project. Armed with a handgun, he forced everyone inside and held them hostage. After hours of negotiation, two of the friends were released, leaving only Eloá and her best friend, Nayara Rodrigues da Silva. From that moment on, the apartment became a stage — surrounded by police, reporters, and cameras broadcasting every movement live.

For more than 100 hours, the standoff unfolded in real time. Major television networks set up outside the building, airing interviews with the hostage-taker over the phone and even broadcasting police negotiation tactics. At one point, the police allowed Nayara — who had been released earlier — to return to the apartment, a shocking and dangerous decision that defied international protocol. Viewers across Brazil watched as journalists, not law enforcement, seemed to mediate the crisis.

The result was catastrophic. On October 18, after five days of failed negotiations, police stormed the apartment. Lindemberg opened fire. Nayara was shot in the face and survived; Eloá was struck in the head and the groin and died a few hours later in the hospital. The entire country watched it happen — a murder played out live, the ultimate failure of both policing and journalism.

Lindemberg was later convicted of murder, attempted murder, and false imprisonment, and sentenced to nearly 100 years in prison (later reduced to 39). He remains incarcerated in the Tremembé penitentiary. But the deeper wound — the collective guilt — has never fully healed.

The new Netflix documentary, directed by Cris Ghattas and produced by Paris Entretenimento, reconstructs the case through never-before-seen footage, interviews with Eloá’s family and friends, and excerpts from her personal diary. For the first time, the focus shifts away from the killer and toward the victim — the teenage girl silenced by both her abuser and the sensationalist machine that turned her death into a ratings phenomenon.

Critics have praised Caso Eloá – Refém ao Vivo for its sensitivity and historical distance, calling it “a mirror held up to our worst instincts.” Yet the film also exposes the paradox of true crime: to condemn voyeurism, it must first recreate it. It’s impossible to watch without feeling complicit. Seventeen years later, the same media logic that exploited Eloá’s tragedy now repackages it for streaming algorithms — proof that pain, even when revisited, still sells.

Watching it, I felt both admiration and unease. The film succeeds in giving Eloá back her voice, but it also reminds us of our own — the millions of voices that watched, speculated, and judged in real time. The police mishandled the operation; the press turned it into theater; the public couldn’t look away. And now, years later, we consume it again — polished, edited, algorithm-approved.

Perhaps that’s why Caso Eloá – Refém ao Vivo feels so necessary. It’s not just another true crime entry; it’s a reckoning. The story of a girl who fell in love too young, tried to escape abuse, and became a symbol of everything Brazil still struggles to confront — gender violence, media ethics, and institutional failure.

Eloá Cristina Pimentel never asked to be remembered as a headline. But her story continues to demand that we look harder — not at her death, but at ourselves.

Because revisiting the crime is easy. Learning from it is the hardest part.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.