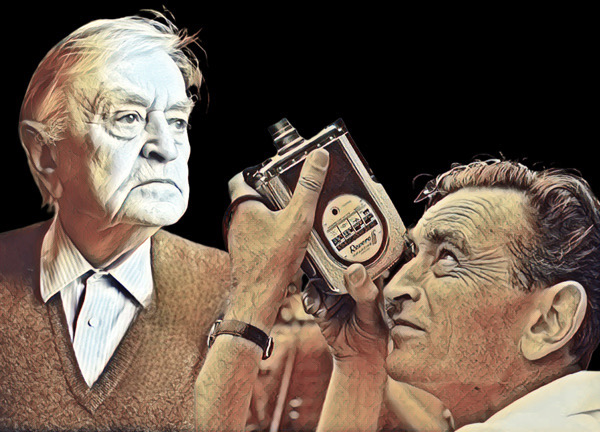

Among the great architects of 20th-century cinema, few are revered with the devotion reserved for David Lean. He filmed rarely — only 17 features — but filmed as if carving in stone. His body of work is not vast, yet it is colossal, and a quick look at the arc of his career is enough to understand why so many filmmakers still regard him as the most rigorous, elegant, and masterful of them all. After setting the world ablaze with Lawrence of Arabia in 1962, Lean returned three years later with an epic moving in the opposite direction: if Lawrence was the sun, Doctor Zhivago would be the snow; if one embodied the imperial triumph of the desert, the other captured the intimate collapse of a convulsed Russia.

Released in December 1965, Zhivago reached its 60th anniversary in 2025 with its status as a masterpiece fully preserved. It is remarkable how a film conceived as a historical melodrama — and criticized at the time for being “too romantic” and “not political enough” — became one of the greatest epics ever committed to film. Its power lies not only in its scale, but in its precision. Lean understood the delicacy with which a story can travel across generations, and even after directing monumental productions, Zhivago endures as cinema in its most emotional and timeless form.

The adaptation was born surrounded by controversy. Boris Pasternak’s novel, written over the course of a decade and published in the West in 1957, was immediately banned in the Soviet Union. It’s “crime”? A humanistic, individualistic, lyrical vision. Pasternak did not glorify the Revolution; nor did he echo the official voice of socialist realism. On the contrary, he exposed the moral complexity, systemic violence, and human impact of Russia’s transition from czarism to Bolshevism. The regime regarded the book as deviant — almost traitorous — and transformed it into a symbol of cultural resistance. Forbidden at home, it became indispensable to the world.

Lean fell in love with this explosive intersection of character and historical moment. Unable to film in Russia, he rebuilt the country in fragments: Spain, Finland, Canada, England. The winter of 1964 was the warmest in fifty years, forcing the team to invent snow out of marble dust. Thus emerged the melancholy landscape that, to this day, defines the Western imagination of revolutionary Russia.

If the imagery of Doctor Zhivago is indelible, much of that power also comes from Maurice Jarre’s score. It is impossible to think of the film without instantly hearing the first notes of “Lara’s Theme,” the melancholy waltz that drifts through the narrative like the very memory of a doomed love. Later transformed into the popular song “Somewhere, My Love,” the melody escaped the screen, filled radios, dance halls, and living rooms, and helped fix the film in the collective imagination far beyond cinephile circles. Jarre composes not merely background music, but an emotional commentary: the score stitches together eras, distances, and shifting regimes, reminding the viewer, each time the theme returns, that beneath History there is still a stubborn, beating heart.

Robert Bolt’s screenplay required drastic choices. The novel is immense — Pasternak weaves dozens of characters, multiple political phases, and long passages of poetry. Lean and Bolt knew a faithful adaptation would demand forty-five hours of film. They chose, instead, to preserve the essential: Yuri, Lara, war, love, ruin, and the survival of the individual within History. Much was cut — entire characters, political digressions, poetic reflections, shifts in time and geography. But something fundamental remained: the delicacy of a story that exists only because life insists on seeping through the cracks of chaos.

Yuri Andreyevich Zhivago, the character who gives the novel its name, is a man made of delicacy in a brutal world. Orphaned in childhood, he grows up with a sensitivity that never dissolves: the serene melancholy, the curiosity before life, and the almost physical need to record the world through poetry. A doctor by ethical vocation and a poet by inner urgency, Zhivago lives the contradiction of trying to heal bodies while attempting to understand the soul of a fractured country. He is neither a hero nor a revolutionary; he is an observer — someone for whom empathy matters more than any doctrine. This refusal to dehumanize the other, at a time when everything demanded radicalization, turns him into a quiet symbol of resistance. Even in chaos — amid war, loss, hunger, and exile — Zhivago keeps writing. His poems are the final proof that, despite everything, he remained whole. Poetry is his legacy and, in the end, the reason the book bears his name: through his words survive the memory, the love, and the tragedy of Lara.

Yes — because at the center of this wartime romance stands Lara Antipova, whom Pasternak described as “the feminine soul of Russia.” Her trajectory is one of the most devastating in 20th-century literature. She begins as a young woman marked by social circumstances that leave her vulnerable to male power and to the moral hypocrisy of her time. Viktor Komarovsky, an older, influential, and manipulative man, seduces her — in truth, coerces her — in a long, destructive, and traumatic relationship. Attempting to break this cycle, Lara makes a dramatic choice: she goes to a reception armed and shoots him. The violence of this act is her first gesture of autonomy — the moment she refuses to remain a victim, even at a high cost.

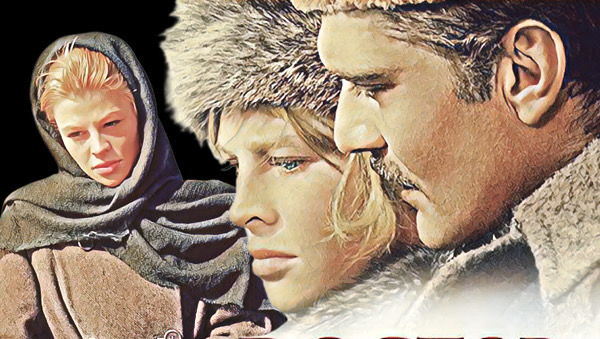

Attempting to rebuild her life, she marries Pasha Antipov, an idealistic young man who adores her but does not understand her shadows. When World War I erupts, Pasha disappears, and Lara enlists as a nurse to search for him. This is where she meets Yuri Zhivago. For months, the two work side by side in a field hospital: he, a doctor and poet; she, a woman trying to preserve dignity in a collapsing world. They recognize in each other a kind of emotional refuge — silent, inevitable — although Yuri remains faithful to his wife, Tonya.

Years later, with Russia overtaken by civil war, they meet again in Yuriatin. It is there that their love is finally consummated, though always on the edge of danger. The Cheka monitors Lara because of her connection with Pasha, now radicalized under the name Strelnikov. Komarovsky returns to warn her of the real risk of arrest. Lara agrees to flee, but Yuri — convinced that his presence endangers her — stays behind. It is one of the most heartbreaking gestures in film history: in trying to save her, he loses her. On the train, Lara reveals she is pregnant with Yuri’s child; life insists, even in ruins. Her fate ends in silence: after Yuri’s death, she appears briefly and then disappears, likely sent to a gulag. No record, no body. Only an absence that becomes legend.

Lean found in Lara the light of the film, and Julie Christie — with her wounded beauty and luminous dignity — became the definitive embodiment of this tragic character. Omar Sharif, chosen after Peter O’Toole, Paul Newman, and Max von Sydow turned down the role, lends Yuri a melancholy so pure that his face has become inseparable from the character. The cast is completed by Geraldine Chaplin, Rod Steiger, Alec Guinness, and Tom Courtenay — one of the greatest actors of his generation — each contributing to the emotional mosaic of this reimagined Russia.

Doctor Zhivago premiered to mixed reviews. Critics accused it of romanticizing the Revolution and trivializing politics. Yet even those who objected acknowledged its hypnotic beauty. Audiences embraced it immediately: the film received ten Academy Award nominations and won five, including Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Score, and Best Cinematography. Adjusted for inflation, it remains among the highest-grossing films in history.

It is striking how Lean, in his obsession with scale and detail, created a cinema that depends as much on geography as on emotion. Lawrence of Arabia, his longest film, running 222 minutes, is the apex of this monumental impulse. Zhivago, with roughly 193 minutes, is shorter — but perhaps his most intimate work. It is the epic of the gaze, of snow, of a train crossing the horizon, of a love that cannot exist and therefore burns even more fiercely.

If Lawrence is a masculine odyssey about heroism and desert, Zhivago is an elegy to the way love insists on blooming in the winter of History. Sixty years later, its impact endures. David Lean filmed a country that no longer existed, froze emotions in a palette of ice and light, and turned the tragedy of an era into pure poetry. No one else filmed like this. Perhaps no one ever will.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.