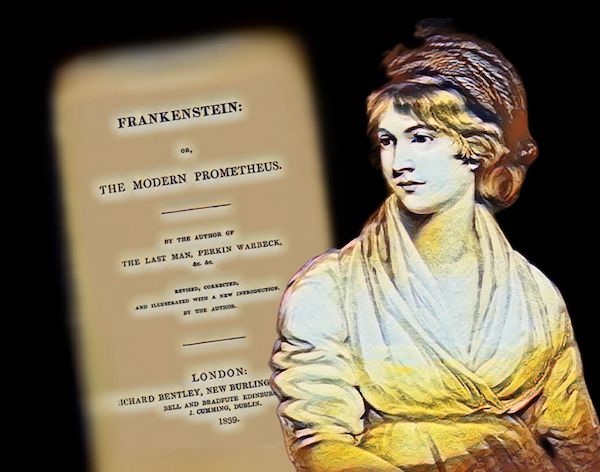

While some say that classics survive time out of sheer stubbornness, others survive because time itself insists on returning to them. Frankenstein belongs to a much rarer category: a novel that seems to have been written for a future Mary Shelley could never witness.

Published anonymously in 1818 in a tiny print run of 500 copies on the cheapest paper available, the book crossed wars, revolutions, scientific upheavals, cultural shifts, and technological reinventions — and more than two hundred years later, it still finds new readers every year. Unsurprisingly so: this is one of the most “alive” works in the canon, with steady annual sales of around forty thousand copies and an astonishing peak in 2016, when it came close to fifty thousand. Few 19th-century novels can claim this kind of vitality. Very few, in fact, can claim this kind of continual rebirth.

What makes Frankenstein so singular is not only its plot — the ambitious scientist, the abandoned creature, the tragic mechanism that binds the two — but the exceptional convergence of tensions Shelley wove into her narrative. The novel breathes pure Romanticism, with its emotional excesses, its sensitivity to the sublime, its reverence for nature as a force capable of healing or destroying. Yet it also embodies the Enlightenment pushed past its own limits, with its suspicion that human knowledge can and should exceed every boundary.

Victor Frankenstein is the beloved child of both impulses: aspirational, feverish, dazzled by the possibility of penetrating “the secrets of heaven and earth,” and utterly incapable of taking responsibility for what he creates. The creature, ambiguous and heartbreaking, born as a metaphor for emotional orphanhood and social neglect, feels even more contemporary today. Looking at humanity from the outside, he sees its cruelty and its tenderness, its beauty and its violence, and understands — long before his creator does — that monstrosity rarely comes from birth; it comes from abandonment.

This ambiguity, this oscillation between light and darkness, reason and emotion, science and guilt, is perhaps why Shelley’s novel never stopped being reinterpreted. Its layers are endless. Frankenstein can be read as a critique of modern rationalism, an allegory of the French Revolution, a narrative about maternal anxiety, postpartum depression, trauma, colonialism, slavery, social revolt, ecology, artificial intelligence, bioengineering, and unchecked technological ambition. None of these readings cancels the others; they accumulate, multiply, evolve as the world changes. The novel is inexhaustible because it is not about a monster at all — it’s about a human impulse, an ethical and emotional mechanism that still moves us. Whenever technological progress outpaces our emotional capacity to absorb it, Frankenstein returns as a diagnosis.

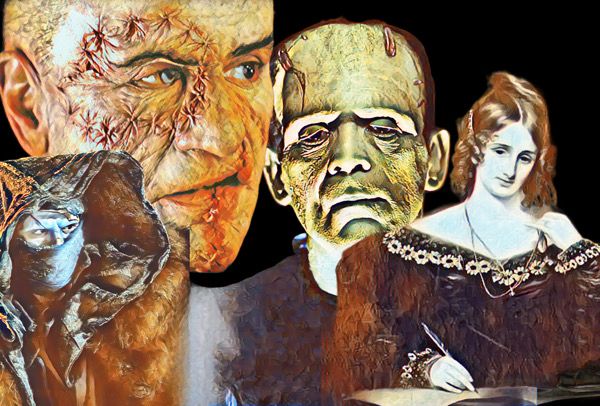

That is why the creature became one of the most reproduced icons in cultural history. From the first cinematic adaptation in 1910, through James Whale and Boris Karloff’s 1931 classic, through Hammer Films in the 1950s, Mel Brooks’s brilliant 1974 parody, musicals, animations, graphic novels, and Danny Boyle’s 2011 stage production with Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller, all the way to the highly anticipated Guillermo del Toro version — each retelling reignites the myth and gives the original book a new layer of meaning. And the public responds: they read, reread, rediscover the original text. The 2016 sales peak did not happen in a vacuum; it was fueled by this cultural cycle of adaptations, academic debates, and a growing generational fascination with narratives that interrogate the limits of human creation.

This movement seems to be repeating itself now. Del Toro’s adaptation, the heated discussions about artificial intelligence, scientific leaps that test ethical boundaries, and the broader revaluation of classic works by women create a fertile environment for the novel’s return to the center of contemporary conversation.

Nothing suggests Frankenstein is losing momentum; on the contrary, everything indicates we may be entering another wave of renewed interest, perhaps as big as 2016 or larger. When new readers discover that Shelley’s creature is not the green, bolt-necked caricature popularized by Hollywood but a sensitive, articulate, tragic being, something shifts. They want to go back to the original text, to the intensity with which Shelley wrote about loneliness, responsibility, fear, creation, and abandonment.

And that, ultimately, is what keeps the novel alive: its ability to speak to the present without severing its ties to a turbulent past. Shelley, who wrote the book after dreaming that her dead baby could be brought back to life, projected into the creature her own ghost: the devastating question of what happens when what we create — children, ideas, technologies — finds no place in the world. The creature that terrifies Victor is, above all, the reflection of the human inability to sustain what it gives life to. And that theme, so deeply bound to modern experience, may never have been more necessary.

Einstein once said that good ideas become “inevitable.” Frankenstein, with its interplay of rationality and excess, tenderness and horror, philosophy and intimate tragedy, is inevitable. It is the novel that returns every time we advance a little further. It is the book that resurfaces whenever the world seems ready to cross a threshold it cannot yet name. And now, with new generations arriving, with cinema preparing yet another metamorphosis, with ethical and technological debates veering dangerously close to fiction, it feels almost certain that Mary Shelley will be read again with the urgency of someone reading the future.

Because Frankenstein was never about a monster. It was always about the human being trying to survive the consequences of its own ambition. And that, two hundred years later, remains the most pressing story of our time.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.