I resisted watching After the Hunt, by Luca Guadagnino. First, because the reviews were lukewarm, when not outright harsh. Then, because the subject itself — abuse, cancel culture, academia, generational clashes — already came burdened with too much real-world noise. But here I am, won over by an extremely interesting and necessary film, precisely because it offers no comfort at all.

Each viewer may cling to a different axis: some see a study of cancel culture, others of feminism, others of academic politics, others of abuse of power, generations in collision, intellectual vanity, and institutional hypocrisy. All of that is there. But for me, After the Hunt is, above all, a direct and uncomfortable story about the weight of forgiveness, expectation, truth, and guilt — four forces that seem to define us more than any ideology.

And it’s striking how the film uses music as a silent moral conscience. While classics by The Smiths and The National drift through the background as modern melancholy, it is the Brazilian song “É Preciso Perdoar” that echoes like a verdict. Not as a solution — but as a provocation. Because the entire film seems to ask: really? Must one forgive at any cost?

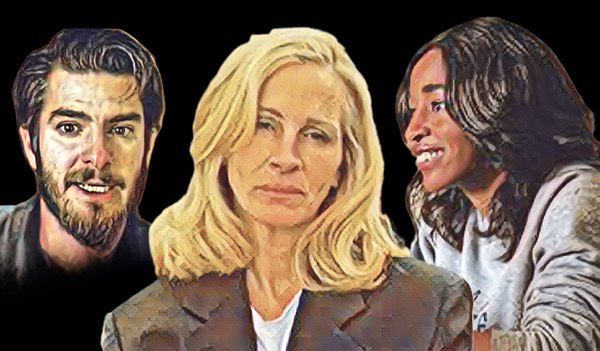

Julia Roberts, in her best performance in many years, carries that question in her body. Her Alma is a brilliant, powerful, respected, admired woman — and completely fractured on the inside. A philosophy professor who knows how to theorize about the world, but fails to deal with her own ghosts. A feminist with a real history of struggle, yet trapped in contradictions she herself learned to normalize. A victim who, at some point, learned to survive through silence.

What Happens After the Hunt (No Frills, Just the Story)

(From this point on, there are spoilers.)

Alma Imhoff is a philosophy professor at Yale on the verge of securing her long-awaited tenure. Around her orbit, two characters who will detonate the bomb:

Hank (Andrew Garfield), a departmental colleague — brilliant, resentful, a high-functioning alcoholic, an intimate friend and, at times, perhaps something more than that;

Maggie (Ayo Edebiri), a graduate student, young, Black, wealthy, gay, Alma’s protégée and declared admirer, but also someone who uses that closeness as a currency of power.

Everything seems to revolve around the very specific comfort of that world: dinners, sophisticated debates, books, art, cozy interiors, the fantasy that only intelligence and merit exist there. One night, Alma and her husband — a psychoanalyst who oscillates between support and passive sabotage — host colleagues and students at their home. Alcohol flows freely, boundaries blur, hierarchies soften. The party ends with Hank, visibly drunk, walking Maggie home.

Hours later, Maggie reappears at Alma’s door in shock, accusing Hank of having sexually assaulted her. From that point on, what the film undertakes is not exactly a “who did what” investigation, but a moral dismantling: Hank (who denies the abuse) plays the victim; Maggie oscillates between genuine vulnerability and behaviors that can be read as manipulation, privilege, crisis, and desperation — all at once; and Alma finds herself at the center of a crossfire: between loyalty to her friend, responsibility toward her student, fear of losing her career, and the weight of her own history of abuse, which she never truly processed.

Hank is fired. Maggie takes her version to the press. Alma tries to rationalize choices that are, at their core, sheer self-preservation. The university enters full crisis-management mode. And from that point on, everything unravels in Alma’s life in a tangle of layers in which the film refuses to give us what we most desire today: easy answers. After the Hunt does not allow us to resolve the narrative the way we resolve an internet tribunal. It forces us to remain in the murky territory where trauma, interest, power, fear, vanity, and self-preservation coexist.

My personal reading of Maggie, Alma, and Hank

My personal reading, based on Maggie’s decision to snoop through Alma’s house and to keep what later becomes a crucial piece of the professor’s buried past, is that honesty is not her strong suit. The way she looks at Alma reveals obsession and competitiveness. Combined with the fact that Alma’s great secret is precisely that she once accused an “innocent” man in the past, this leads me to the conclusion that Hank did nothing.

That does not mean he is incapable of abusive behavior — his final scene with Alma confirms that — but he did nothing to Maggie beyond confronting her about plagiarism.

In the end, Maggie is like an Eve Harrington from All About Eve, obsessed with Alma, and when she senses her mentor’s hesitation to fully embrace her narrative, she turns against her. However — and here lies the unsettling beauty of After the Hunt — she does not act only because of this, but because she genuinely thinks like her generation. Millennial women are often offended by older generations of women for not having broken with patriarchy, but rather having learned to coexist with it. That is why, when she directs her revolt toward Alma, she hits a target she knew by instinct, even if it was not obvious (Alma only confesses everything to her husband at the end). Hence, the film’s deeply uncomfortable quality.

As for Alma, it is worth stressing what Maggie reveals, and Alma denies: the professor is like so many victims of abuse — she blames herself and still defends the abuser. In her case, Alma had an affair with a friend of her father’s when she was only fifteen. When she was later abandoned, she accused him of rape. Because she believes the relationship to have been “consensual,” she considers herself to have lied. But it was statutory rape. Technically, she told the truth, yet even at sixty, with a PhD in philosophy, she still believes she “lied” because she exposed him out of revenge. That story alone could sustain an entire film.

Cut! The final scene: why does it disturb so much?

If there is a moment that truly deserves the label “controversial,” it is the final scene — not only for what happens, but for what doesn’t happen. Years after the scandal, we meet Alma and Maggie again, both with successful lives: Alma as dean, Maggie now engaged to be married.

They meet in an Indian restaurant and, for the first time, speak not as professor and student, mentor and protégée, victim and accomplice, but as two women who share intimate knowledge of one another: both know what it means to be wounded by a man in a position of power. Both know that, in different ways, they reproduced the very systems that hurt them. The dialogue is a classic exercise in passive aggression, but the discomfort of the scene lies in the fact that no one there is exemplary.

Instead, the film delivers something far more bitter: in the appearance of a general victory (Alma becomes dean, Maggie is now a successful academic, and Hank is in politics), there is no exemplary punishment. What exists is a kind of silent pact among those involved and a complex social system. And we almost hear the director say “cut,” in a surprising break of the fourth wall that reminds us that this is, after all, only a film.

For us Brazilians, who know the lyrics of “É Preciso Perdoar,” this is where the music, the theme of forgiveness, and the title of the film collide at last. After the Hunt shows us neither explicit forgiveness nor formal revenge. What it shows is something far more unsettling. No one there truly seems to forgive. Everyone merely manages their own narrative. Forgiveness would require dismantling entire identities — and no one is willing to do that. And perhaps that is precisely what the film gets most right: it understands that we are made of unbearable contradictions, and that public discourse — whether of cancellation or absolution — rarely accounts for intimate complexity.

In the end, After the Hunt is not only about abuse. It is about what we do after: after the accusation, after the fall, after reputation, after silence, after incomplete truth. It is about who survives. And at what cost? And perhaps the cruelest truth of all: it is about how some people win the hunt — yet continue to be slowly devoured from the inside.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.