As 2025 enters its final weeks, anyone who cares deeply about Cinema, Theatre, and Music can feel the weight of a year marked by the loss of great names. Some are instantly recognizable faces. Others live mostly behind the scenes — and people pause and ask: who? Mourning the death of playwright Tom Stoppard falls squarely into that second category.

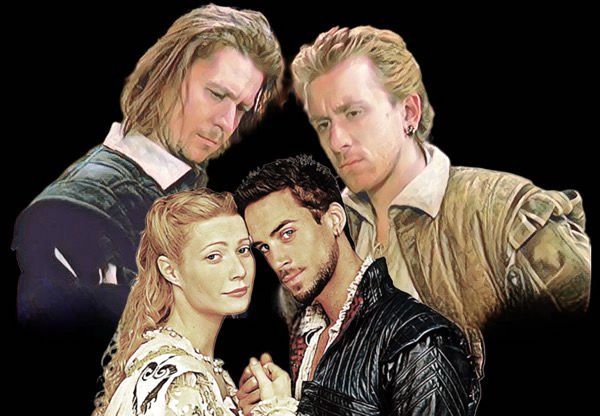

Stoppard’s legacy is far greater than his most famous film, the one that earned him an Academy Award, but it is often the gateway: Shakespeare in Love, a late-1990s classic, a romantic comedy that is imaginative, playful, and remarkably precise. Yet Stoppard came from the theatre. He knew Shakespeare intimately, and long before Hollywood embraced him, he had already reimagined the Bard by pulling two minor characters out of Hamlet — Rosencrantz and Guildenstern — and turning them into the leads of a brilliant play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, later adapted for the screen with Gary Oldman and Tim Roth.

He also signed the screenplays of major films such as Brazil, Empire of the Sun, The Russia House, Hugo, and Anna Karenina. He truly was extraordinary.

Tom Stoppard was not born Tom Stoppard. His birth name was Tomáš Straussler. He was born in 1937 in what was then Czechoslovakia and, still a child, was forced to flee with his family from the Nazi occupation. Their path of survival took them through Singapore and then to India — where his father would die during the war — before finally reaching England. There, Tom adopted his stepfather’s surname and grew into one of the most “British” voices in modern drama.

He was not shaped by elite academia. At 17, he became a newspaper reporter in Bristol, writing about everything while quietly falling in love with the theatre as an obsessive spectator. With no university education and no traditional intellectual pedigree, he built himself through reading, watching, listening, failing, and rewriting.

Everything changed in 1966 with the premiere of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. The play, which views Hamlet through the eyes of its doomed bit players, turned chance, death, and free will into a dazzling existential comedy. From that moment on, Stoppard was labeled “the most cerebral playwright of his generation” — a description that followed him for the rest of his life, sometimes as praise, sometimes as suspicion.

Then came Jumpers, Travesties, The Real Thing, Arcadia, Rock ’n’ Roll, and the vast trilogy The Coast of Utopia. Arcadia, in particular, became a kind of distilled Stoppard: science, poetry, mathematics, desire, irony, flirtation, and heartbreak all sharing the same space, across two centuries, without ever feeling forced.

For years, critics said his work lived only in the mind and not in the heart. Stoppard listened. Something shifts in the 1980s. The Real Thing places love at the center of its drama without sacrificing intellectual rigor. Later, politics enters more forcefully, especially when he revisits Czechoslovakia, the Prague Spring, oppression, and music as resistance. The man who once claimed not to “burn for causes” became, in his maturity, a powerful and subtle voice for freedom.

In the 2000s, already celebrated worldwide, he delivered his most personal work: Leopoldstadt. Following a Jewish family through the first half of the 20th century in Central Europe, the play reads like a delayed reckoning with his own past — the lives left behind when the refugee child escaped. In his eighties, Stoppard finally allowed history to strike with full emotional force.

In film, he was equally singular. He won the Oscar for Shakespeare in Love, but his signature extends across dystopias, war dramas, espionage stories, and literary adaptations. He moved effortlessly between the most cerebral theatre and mainstream cinema, never losing his voice in either world.

Tom Stoppard died on November 29, 2025, at the age of 88, in his home in England. He leaves four children, his wife, and a body of work that continues to be staged, studied, and rediscovered.

Perhaps his greatest achievement was convincing us, time and again, that thinking can be a pleasure. Those ideas can move us. That humor can carry philosophy. And that is when language finds its perfect form, the stage becomes one of the most alive places in the world.

In a year full of farewells, Stoppard’s feels uniquely painful. We lost someone who believed, fiercely, in the power of words — and who, like few others, knew how to turn them into spectacle.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.