In general, when people think of David Lean, they think of grand epics: monumental landscapes, operatic running times, deserts, and empires. Yet for devoted “Leanians,” it is precisely a small film that is most often considered his greatest achievement. A beautiful, compact black-and-white work, built from silences and interrupted gestures — an intimate jewel inside the career of a master of spectacle. A pearl that, over the decades, has gained new readings, new generations of admirers, and that continues to influence cinema eight decades on.

Yes, in 2025, Brief Encounter turns 80 years old. The number is striking, yet its impact remains intimate, almost inaudible — like a train passing in the background while two people try to say goodbye without drawing attention. Few films travel so many decades without losing the power to touch the exact same vulnerable place in the viewer: the territory where desire, guilt, longing, and self-restraint converge.

The irony is that, at its very first public screening, audiences laughed. They laughed at the wrong moments — at the excessive restraint, at the emotion that never exploded. Lean left the screening embarrassed, briefly considering breaking into the laboratory and destroying the negative. Time would do exactly the opposite of what he feared: it would transform that fragile melodrama into one of the pillars of 20th-century romantic cinema. Decades later, the British Film Institute would rank it as the second-greatest British film of all time. Greta Gerwig would call it “the most romantic movie ever made.” And filmmakers as different as Sofia Coppola, Wong Kar-wai, and Celine Song would recognize in it a secret matrix for their own films.

A banal meeting, an irreversible detour

Laura Jesson is an ordinary housewife — a painfully middle-class woman. Every Thursday, she travels to the town of Milford to shop, go to the cinema, and have tea. Her routine is so carefully organized that it borders on emotional anesthesia.

One day, at the railway station, a speck of dust enters her eye. A passing doctor, Alec Harvey, steps forward to help her. A minimal gesture — and an irreversible shift begins. They meet again by chance at the chemist’s, then at a café, then at a matinee. Little by little, they begin to arrange their encounters.

Both are married. Both know it should not exist. And yet it does. First as simple companionship, then as something they can no longer name without guilt. What begins as a distraction slowly becomes a threat to the equilibrium of an entire life.

Love as interruption, not as destiny

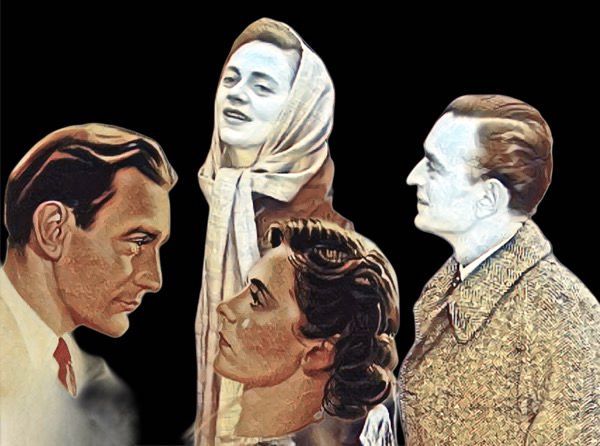

Laura, played by Celia Johnson in one of the most delicate performances in cinema history, narrates her story as a silent confession addressed to a husband who knows almost nothing. Judgment does not come from society. It comes from within.

Alec, portrayed by Trevor Howard, is equally restrained: a gentle, proper man, emotionally disarmed. The tragedy is not born of an explosion. It is born of slow erosion.

After a series of meetings in public places, they attempt — only once — to break the spell of restraint. They go to a friend’s flat. The friend returns unexpectedly. Everything collapses. Laura flees, walks alone through the city for hours, sits on a bench, smokes, and confronts her own inner ruins. Consummation never occurs. Adultery exists only in imagination — and yet guilt is absolute.

Soon after, Alec announces that he has accepted a medical post in South Africa. Geography becomes a moral escape. They meet one last time in the station tea room, but an oblivious acquaintance interrupts them. The train arrives before they can speak. Alec merely squeezes Laura’s shoulder. Later, she nearly throws herself in front of another train. Nearly. The entire film lives in that nearly.

She returns home. Her husband senses her distance. Perhaps he suspects. Perhaps not. He takes her hand and simply says, “Thank you for coming back to me.” She weeps. Not because she has been forgiven — but because she has survived what she will never be able to live.

The music of what cannot be said — from Sergei Rachmaninoff to pop

Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto does not illustrate the film — it speaks for it. Where Laura cannot speak, the piano erupts. Where morality demands containment, harmony overflows.

The melody itself was born from the composer’s struggle with depression in the early 20th century. It passes through the misty platforms of Brief Encounter and re-emerges decades later in pop culture through Eric Carmen’s All By Myself. The same emotional wound migrates from concert hall to cinema, from cinema to radio, from private despair to collective memory.

From Still Life to the screen: the heart of the story was already there

Before it was a film, Brief Encounter was a short play: Still Life, written by Noël Coward in 1936 as part of the Tonight at 8.30 cycle. At a time when one-act plays were considered unfashionable, Coward insisted on the form precisely because he believed a short piece could sustain an emotional climate with greater precision.

Still Life was the most melancholic work of the cycle. On stage, Coward himself played Alec opposite Gertrude Lawrence as Laura. All the action took place in the tea room of Milford Junction station, across five scenes spread over one year. The emotional spine was already complete: chance encounter, guilt, South Africa as moral escape, and the farewell ruined by an inconveniently chatty friend. Even Laura’s suicidal impulse before the passing train was already suggested in the play — cinema would only make it explicit.

What changed was scale, not essence. The film gave breath to spaces, but did not alter the nerve of renunciation that defined the story from the start.

A film between three times: war, pre-war, and post-war

Brief Encounter was shot in 1945, during the Second World War, but set in pre-war England and released to a post-war audience. It exists in a peculiar triangle of time: conceived under rationing, set in a vanished moral world, and watched by spectators already marked by real separations.

Filmed largely at Carnforth station in northern England, under the real risk of air raids, the movie physically carries the tension of a nation suspended between loss and reconstruction. When it first opened, it was not a failure — but neither was it an immediate phenomenon. Its prestige would grow gradually, especially through television, until it became a piece of British emotional heritage.

Class, repression, and the moral weight of “no”

Laura and Alec’s love is profoundly shaped by class consciousness. To betray is not merely a social error; it is an identity failure. In Laura’s case, however, the greatest obstacle is internal. The horror of recognizing herself as adulterous weighs more heavily than desire itself.

In her narration, she tries to organize her emotional vertigo through logic and self-control — at one point telling herself that “nothing really lasts, neither happiness nor despair.” It is an attempt to turn love into something temporary, manageable, finite. The film, however, quietly dismantles that reasoning. What should pass, remains. What should dissolve, condense? And it is precisely in the failure of reason that Brief Encounter discovers its most enduring strength.

Later readings, especially after Coward’s death and the posthumous acknowledgment of his sexuality, would also interpret the film as an allegory of censored LGBTQ+ love — of relationships forced to exist only in thought, silence, and longing.

The lineage of the “what if?” in cinema

Billy Wilder in The Apartment. Kazuo Ishiguro in The Remains of the Day. Sofia Coppola in Lost in Translation. Wong Kar-wai in In the Mood for Love. Celine Song in Past Lives. All are, directly or indirectly, heirs to the same elegant trauma inaugurated by Brief Encounter: the life that might have been.

The remake that proved the original’s singularity

In 1974, Brief Encounter was remade for American television under the banner of the Hallmark Hall of Fame, starring Sophia Loren and Richard Burton. Despite the prestige of the pairing, the remake was met with indifference and quickly forgotten. The plot survived, but the atmosphere did not. It unintentionally proved that Brief Encounter is not merely a script — it is a rare product of its time, its culture, and its invisible moral landscape.

From stage to the 21st century: Brief Encounter reborn in the theatre

In the 21st century, the story found one of its most inventive reincarnations on stage. In 2007, director Emma Rice, with the Kneehigh Theatre, created a bold adaptation that fused the screenplay of Lean’s film with elements from Coward’s original Still Life. The production premiered in Birmingham and quickly became a theatrical sensation.

Blending live cinema, music, physical theatre, and delicate humour, the staging preserved the tragic core of the story while radically renewing its form. In 2008, it transferred to London’s West End, and in 2009 crossed the Atlantic to New York, enjoying a celebrated Broadway run at Studio 54. Over the following decade, the production continued to tour internationally — returning repeatedly to the UK, and travelling through Australia and the United States. For a story built entirely on a single, unrepeatable encounter, it is almost ironic that Brief Encounter became one of the most frequently revived romantic tragedies of contemporary theatre.

When silence turned into song: Brief Encounter as opera

In 2009, the story underwent yet another improbable transformation: it became an opera. Composer André Previn set Brief Encounter as a two-act opera with a libretto by John Caird. The world premiere took place at the Houston Grand Opera, starring Elizabeth Futral as Laura and Nathan Gunn as Alec.

What had always lived in silence, restraint, and interior monologue was suddenly given full lyrical voice — a radical shift of language that nonetheless remained faithful to the emotional essence of the story. Recorded and released internationally, the opera confirmed Brief Encounter as one of those rare narratives capable of surviving translation across completely different artistic forms.

80 years later: why it still hurts

Because Brief Encounter offers no reparation. No triumph. No reunion. It simply asserts — with almost unbearable honesty — that some loves exist only to reorganize us from within.

To celebrate its 80 years is to celebrate a film that dared to say that not every romance is meant to be lived. Some are meant only to leave their mark — silent, permanent, unerasable.

And that is why, eight decades later, we still return to it with the same question echoing from the misty platforms of Milford Junction to the bars of contemporary cinema:

What if?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.