We step into December, the month in which 30 days almost always feel like far fewer. A month of celebrations and endings, of accounting and hope, of postponed dreams and reinvented plans. A month in which the rhythm of life subtly shifts. And like every important turning point in life, December always comes with a soundtrack.

It starts even before the first day of the month. It’s in shopping centers, in the films that return to television, in blinking lights on windows, in playlists that reappear as if they never truly left. And it’s curious to realize that, although we associate these songs with childhood, nostalgia, and tradition, this bond is also the result of a cultural, artistic, and industrial project built over more than a century.

Christmas music today is not just an emotional memory. It is emotional liturgy, it is business, it is a global synchronized ritual. And all of this began long before pop.

Before pop, before records: when Christmas became emotion shaped by music

Long before radio, records, albums, or streaming existed, Christmas already had its own soundtrack in the world of classical music. And no one was more decisive in this than Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

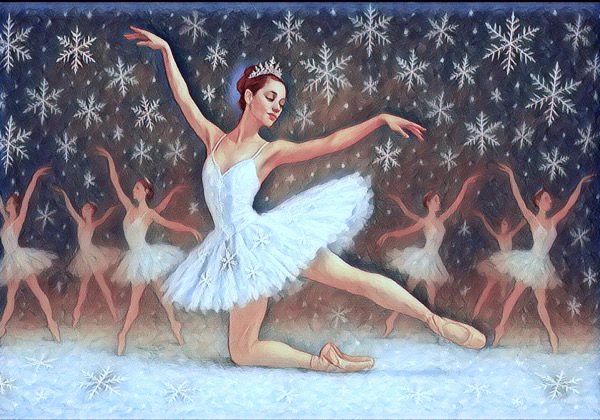

In 1892, with the premiere of The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky did something radical: he transformed Christmas into a complete sonic experience, not as a single song, but as atmosphere, emotional passage, continuous musical dreaming. He didn’t merely create a ballet. He created the definitive climate of the modern Christmas.

“The Dance of the Snowflakes,” the unusual use of choir within a ballet, and the idea of a first act that closes in a state of pure magical suspension — all of this establishes what we instinctively recognize today as the “Christmas spirit”: delicacy, wonder, soft melancholy, childhood, the passage of time, and dream. And the Sugar Plum Fairy, introduced with instrumental colors that were still unheard of at the time, also opened the path for musical daring. With the almost unreal shimmer of the celesta, Tchaikovsky not only invented an atmosphere but legitimized invention, risk, and fantasy as central elements of Christmas sound itself.

Long before anyone sang Christmas, Tchaikovsky taught the world to feel it through music.

Pop would come later. But the emotional architecture was already in place.

The turn of the century and the recorded Christmas

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the phonograph and 78 rpm records, the first commercial Christmas recordings appeared: choirs, hymns, and sacred music. There was still no “pop Christmas market.” It was a devotional sound.

The great turning point arrives in the 1940s, when radio, cinema, and the recording industry align — and Christmas leaves the church to become a mass cultural and emotional phenomenon.

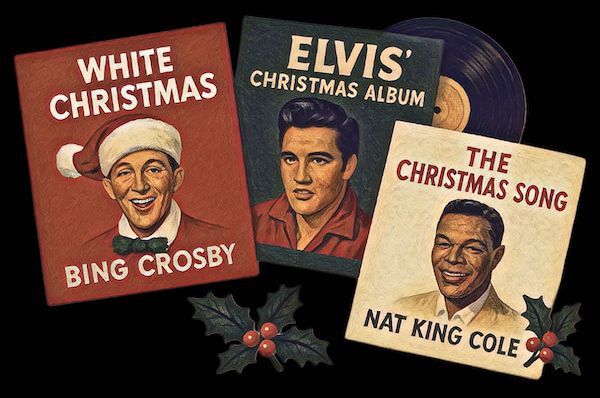

In 1942, Bing Crosby recorded White Christmas. What is born there is not merely a hit: it is a model. The song would become, for decades, the best-selling single in the history of recorded music, crossing wars, generations, physical formats, and technological revolutions.

From that moment on, Christmas definitively leaves the altar and enters the living room.

The Christmas album as a rite of passage

In the 1950s, with the consolidation of the LP, Christmas became a career project. It is no longer just a single song. It becomes concept, cover art, repertoire, identity.

In 1957, Elvis Presley released Elvis’ Christmas Album and proved that even rock can wear Christmas clothes without losing its appeal. Shortly after, Nat King Cole eternalizes an elegant, romantic, orchestral Christmas.

From that moment onward, the Christmas album becomes almost a symbolic initiation: when a career reaches a certain level, the Christmas record arrives.

Over the following decades, with television, end-of-year specials, and the growth of home consumption, Christmas music became an emotional calendar. People come to “know” that Christmas has begun when the songs begin.

The CD era, then streaming: Christmas becomes an eternal asset

With the CD and, later, with streaming, something decisive happens:

Christmas songs stop being just a memory and become cyclical financial assets.

They return every year. They always rise. They always generate revenue.

Today, the market treats Christmas almost like a mathematical phenomenon: in November the numbers climb; in December they explode; in January they sleep — until the next cycle.

Christmas is perhaps the only time of year when the entire world accepts hearing the same songs, in the same order, for decades, without fatigue. On the contrary: with comfort.

The current landscape: the empire of playlists and annual returns

On Spotify and other platforms, Christmas has become a globally synchronized ritual. Christmas playlists are among the most played in the world. Old classics live alongside a very small number of modern hits that have managed to cross the barrier of time.

Today, the logic is clear:

– The traditional repertoire sustains the ritual.

– The pop hits try, little by little, to enter this closed pantheon.

Very few succeed. When they do, they become emotional heritage.

The 10 most listened-to Christmas songs in the world today

- All I Want for Christmas Is You — Mariah Carey

Over 2 billion streams. A phenomenon that repeats like an emotional eclipse every December. - Last Christmas — Wham!

- Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree — Brenda Lee

- Santa Tell Me — Ariana Grande

- Jingle Bell Rock — Bobby Helms

- It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas — today’s most-played version: Michael Bublé

- It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year — Andy Williams

- Mistletoe — Justin Bieber

- Snowman — Sia

- Do They Know It’s Christmas? — Band Aid

Is there a “definitive” Christmas album?

In the modern era, the most cited title is Merry Christmas (1994), by Mariah Carey.

In the classical tradition, Bing Crosby’s albums remain benchmarks.

In the territory of mass pop-religious music, Elvis’s Christmas album remains one of the best-selling of all time.

And long before any record existed, The Nutcracker has, for over 130 years, been the most staged Christmas soundtrack on the planet. An album without vinyl. A stream made of bodies in motion.

Sales, numbers, and the mathematical miracle of Christmas

“White Christmas” surpasses 150 million physical copies sold across history. “All I Want for Christmas Is You” generates tens of millions of dollars each season. On Spotify, the leading Christmas songs accumulate billions of combined streams.

Christmas is perhaps the only musical project that never leaves the catalogue.

Why do we never get tired of it?

Perhaps because Christmas music does not function as ordinary entertainment. It functions as programmed memory. It organizes time. It stitches together loss and reunion, farewell and promise.

By listening to these songs year after year, we are not just hearing music. We are meeting earlier versions of ourselves again.

From Tchaikovsky’s ballet to Mariah Carey’s playlists. From the imperial Russian stage to headphones in traffic. Christmas has always had a soundtrack.

Only the stage has changed.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.