Philip Larkin never had the aura of the poet-hero. He cultivated no grand gestures, wore no tragic-genius costume, chased no spotlight. For almost his entire life, he was a university librarian in Hull — someone who organized shelves of books by day and wrote some of the most unsettling, and most precise, poems of postwar English literature by night. His greatness always lay exactly there: in the way he looked at the ordinary without concessions, stripping it of any easy romanticization.

Published late and sparingly, Larkin built his body of work in a handful of decisive volumes: The Less Deceived, The Whitsun Weddings, High Windows. He became the poet of the English middle class, of the suburbs, of bureaucratic jobs, of marriages that age in silence, of Sunday train journeys, of sexuality crossed by guilt, and of an obsessive awareness of death. His style seemed simple, almost colloquial, but that simplicity concealed a blade: each poem is a dry acknowledgement that life is less than it once promised to be.

Larkin spoke of love, but almost always as loss. He spoke of work as a crushing obligation. He spoke of time not as a promise, but as a constant threat. His poetry is permeated by what critics have called a “civilized disenchantment”: nothing explodes, nothing turns into catharsis, nothing is resolved. Everything simply goes on — until it no longer does.

This gaze, so profoundly English, is also deeply political, though never militant. Larkin writes about postwar Britain without slogans, but with a diffuse feeling of moral impoverishment, of shrunken dreams, of a society that trades ambition for stability and then discovers that stability, too, can oppress.

It is from this world — not of grand utopias, but of small, everyday prisons — that not only Larkin’s poetry is born, but also, decades later, a certain narrative spirit that runs through Down Cemetery Road.

The verse that becomes a road

The very title Down Cemetery Road is taken directly from a line by Larkin, in the poem “Toads Revisited”: “Give me your arm, old toad; / Help me down Cemetery Road.” Here, the “toad” is work — that heavy, inevitable force that settles itself on all our lives. To ask for help in going down Cemetery Road is, ultimately, to ask for companionship in crossing life toward death, carrying the same weight that sustains us and oppresses us.

When Mick Herron chooses this line as the title of his novel — which would later give rise to the series on Apple TV+ — he is not merely making a literary homage. He is declaring an aesthetic and moral lineage.

Herron himself says that, before he had a proper “idea,” he already had three fixed elements: the title taken from Larkin, a woman named Sarah, and a point of view closely attached to her. Everything else would come later. And that is deeply Larkinian: first comes the tone, the existential weight, the road. Plot is almost a consequence.

Sarah: a character who could step out of a Larkin poem

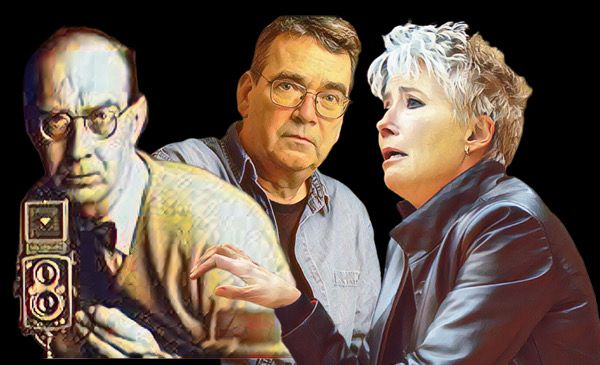

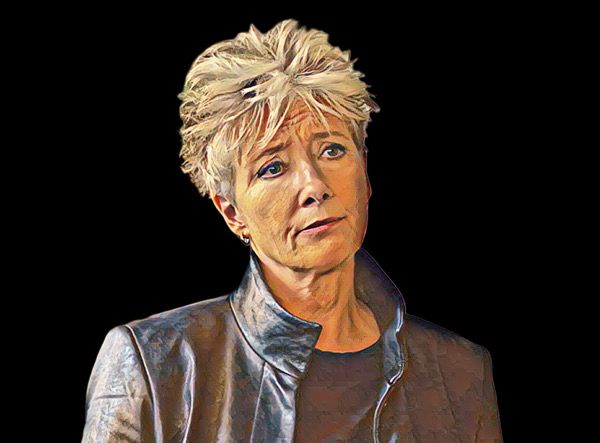

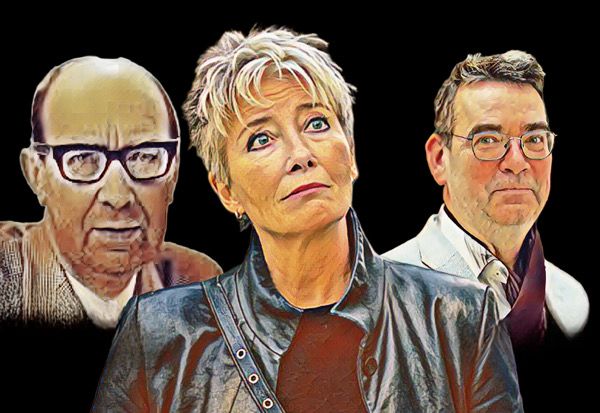

In the series, Sarah is no longer the sole protagonist. Ruth Wilson shares narrative centrality with Emma Thompson, who plays Zoë Boehm (and it is Zoë who recites the poem in the penultimate episode). In the novel Down Cemetery Road, however, Sarah is shaped through an almost mathematical logic, as Herron himself describes: she must be bored, unemployed, childless, supported by a successful partner, living in a neighborhood far too comfortable to allow major ruptures. She must carry small, sophisticated, middle-class resentments. She must feel — without being able to properly name it — that something in her life is wrong.

If we were to replace the police thriller with stanzas, Sarah could easily inhabit Larkin’s universe. She lives precisely in that territory the poet knew so well: a life that appears “well resolved” from the outside, but is eroded from within by dependence, frustration, unresolved desire, and a vague sense of waste.

The event that shatters her routine — the explosion of a house during a dinner party — is itself Larkinian: spectacular enough to shake everything, banal enough to be officially treated as an accident. Nothing could be more coherent with the world of a poet who always distrusted easy explanations and comforting endings.

The “toad” shifts its form.

In the series, the “toad” of Philip Larkin undergoes a decisive displacement: if in the poem it is work — that viscous force that both sustains and oppresses — in Down Cemetery Road, it gains body, affection, and contradiction in the character of Joel.

When Zoë Boehm compares her husband to the “toad,” she is not merely speaking of a man, but of marriage itself as a structure of containment: shelter and prison, love and limit, grounding and immobility. Like work in Larkin, Joel guarantees permanence within the established order, but exacts its price from inner life.

The turning point lies in Zoë’s gesture: while Larkin’s narrators recognize the weight and remain under it, she names it — and in naming it, begins to confront it. The toad ceases to be destiny and becomes conflict.

The suburb as territory of the abyss

Philip Larkin never wrote about grand state conspiracies, but he wrote extensively about something perhaps even more insidious: the way people adapt to a life they never fully chose. His poems about train journeys, birthdays, old photographs, and silent housing estates are studies of time quietly eating away at us from the inside.

Down Cemetery Road performs the same movement, using the tools of the thriller. The investigation into the missing girl dismantles not only a crime, but an entire architecture of apparently stable relationships: marriages, neighborhoods, social hierarchies, pacts of silence. Suspense here arises not only from the mystery, but from the realization that normality itself was a carefully maintained fiction.

That is exactly what Larkin did, poem after poem: he showed that normality is a fragile agreement, and that beneath it, something is always creaking.

Disenchantment as inheritance

What unites Philip Larkin and Down Cemetery Road is not merely a verse reused as a title. It is a worldview: the understanding that life rarely organizes itself around heroic gestures, and that real drama hides in silent kitchens, in unacknowledged dependencies, in lives that keep functioning long after they have lost their meaning.

Larkin believed little in redemption. Herron does too. Both prefer to observe characters trying to balance themselves within systems larger than they are: work, marriage, the State, the mere passage of time.

At its core, Down Cemetery Road is exactly what its title announces: a walk that begins in the dining room of an elegant house and ends — symbolically or literally — at the edge of the cemetery. Not as spectacle, but as everyday destiny.

Why Philip Larkin still matters

Larkin remains relevant because he wrote about what rarely ages: silent inadequacy, the fear of wasting one’s life, the daily negotiation between desire and conformity, the disturbing awareness of death. His world may seem small — libraries, parks, trains, suburban houses — but it is within that reduced space that he uncovers universal truths.

As his poetry crosses into a contemporary thriller like Down Cemetery Road, what becomes clear is that this disenchantment never went away. It merely changed language. What once arrived in verse now appears as explosion, investigation, threat, and conspiracy. But the heart of the story remains the same: ordinary people taking hesitant steps along the same road we all, sooner or later, must walk.

That road.

Cemetery Road.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu