Not every viewer follows the corporate machinery behind what appears on their screen, but the business side of Art has always been as gripping — and often far more dramatic — than the stories it sells. I spent years working as an entertainment executive, parallel to my career as a journalist, and witnessed firsthand the negotiations, tensions, and decisive moments that shaped what we watch, how we watch, and where we watch it. I’ve always found that world irresistible.

Now, I watch it with a lighter, almost domestic curiosity, purely as a consumer — and that, I admit, is a relief. But every time a merger, acquisition, or internal earthquake hits the news, part of me still flinches for the friends who remain inside that ecosystem. For them, these headlines never amount to mere seat-shuffling. They redefine careers, creative identities, and, often, basic professional survival. None of it is simple. None of it is superficial.

And in the last decade, Hollywood has undergone its most profound shift since its creation. Century-old studios, weakened by debt or sidelined by new consumption habits, are being bought by the very companies that displaced them from the center of power. It’s a historical inversion. The latest — and still unfolding — chapter is Netflix’s potential acquisition of Warner. In my view, it is the most significant earthquake the industry has seen in over a century.

Netflix’s entering exclusive talks to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery’s studio and streaming division is not just another financial headline. It encapsulates an entire century of entertainment history in a single move. On one side, the studio that turned 100 in 2023, a pillar of classical Hollywood. On the other hand, the company that began in 1997 by mailing DVDs and, in less than three decades, reshaped global viewing habits. The symbolism borders on cinematic — the end of an era and the dawn of another.

Warner’s presence on the auction block is no accident. AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner in 2018 was a grand gamble premised on the idea that telecom and content were meant to be partners. They were not. In 2021, AT&T unwound the deal and orchestrated a merger between WarnerMedia and Discovery. Warner Bros. Discovery emerged in 2022 already weighed down by roughly $40 billion in debt and an unwieldy hybrid strategy. Reorganizations, cancellations, abrupt budget cuts, and the ill-fated attempt to dissolve the HBO brand into the generic “Max” weakened the company’s identity. Only in 2025 did WBD reverse course and restore the HBO Max name.

Meanwhile, Hollywood consolidated at breakneck speed. Disney absorbed Fox. Amazon bought MGM. Paramount merged with Skydance. Sony and Universal remain independent, but orbit a technological landscape. In this rearranged map, Netflix appears not just as a competitor, but as the new gravitational center.

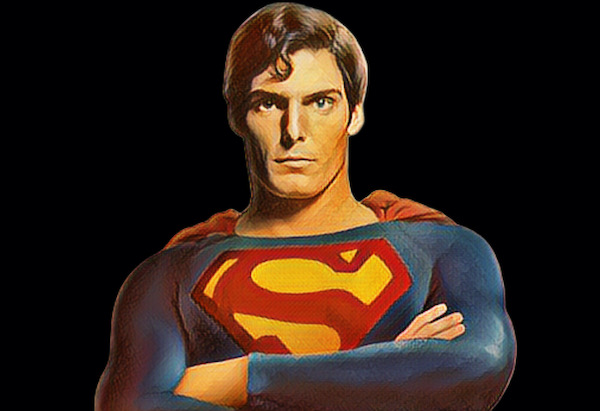

Its proposal to acquire Warner’s studio and streaming division is more than a purchase: it is a statement of power. Netflix wants the catalogue that shaped pop culture — Harry Potter, Batman, Wonder Woman, Game of Thrones, Succession, The Last of Us, The White Lotus, and The Matrix. It wants the physical studios, the international infrastructure, and the HBO prestige. It wants the one element it never fully possessed: pedigree. If the deal closes, Netflix ceases to be merely a platform; it becomes a full-fledged studio conglomerate.

The deal is advanced but not final. The expected signing of the definitive agreement is projected for early 2026 — January through March — followed by internal and shareholder approvals. Regulatory clearance in the U.S. and Europe may take six months to a year. If all goes smoothly, the acquisition will likely close between late 2026 and early 2027.

And if it doesn’t? Netflix agreed to pay a reverse break fee of roughly $5 billion if regulators block the merger — an extraordinarily large “inverted cancellation fee” where the buyer compensates the seller. If the deal collapses, Warner returns to the market weakened, with debt still pressing and rivals circling. For Netflix, it would be an expensive bruise. For Warner, a corporate shock. Within the industry, the question is no longer if but when.

Another layer to this transition is the fate of the executives who shaped Warner and HBO. Richard Plepler, the mastermind behind the “Game of Thrones era,” left with the arrival of AT&T and now produces for Apple TV+. Jason Kilar, who led WarnerMedia during the ambitious — and controversial — decision to release films simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max, exited at the Discovery merger and now sits on tech boards. Ann Sarnoff, the first woman to lead Warner Bros., departed with David Zaslav’s arrival. Toby Emmerich moved into his own production venture. Casey Bloys remains, carrying the creative torch at HBO — and, ironically, may one day steward HBO inside Netflix.

The cultural clash between HBO and Netflix is often framed as “art vs. algorithm.” Tempting — but simplistic. Yes, HBO built its reputation on careful curation and artistic rigor. And yes, Netflix revolutionized consumption through data, retention curves, and global metrics. But neither operates solely in one mode. HBO famously turned down projects that later became cultural phenomena — Stranger Things being the clearest example. The Duffer brothers were rejected by traditional curatorial systems before Netflix took a chance on a project with no algorithmic guarantees. That moment wasn’t data-driven; it was a leap of faith.

We talk about algorithms because they shape the industry now. But entertainment has always relied on numbers. Box office is pure math. TV ratings, however, treated as gospel, were imprecise at best — built on small samples, unrepresentative households, and opaque extrapolations. They were no less “gray” than today’s algorithmic models — simply packaged as certainty. What changes is not the numeracy, but the logic. The old system left room for intuition. The new one eliminates deviations in the name of efficiency.

Still, it would be naïve to ignore that beyond the creative implications lies a structural problem now sending shockwaves through Hollywood and Washington alike: excessive concentration of power. A potential Netflix–Warner merger is not just one more chapter in the ongoing consolidation of entertainment. It would combine the world’s largest streaming platform with one of the last truly independent studio catalogues, a scale that triggers immediate antitrust concerns. What worries agents, directors, writers, and executives is not only cultural dilution, but the possibility that a single company could control production pipelines, exhibition windows, talent negotiations, pricing power, and century-old libraries. Hollywood survived for decades because of plurality: different studios taking different risks, allowing artistic movements to flourish precisely because no single entity dictated the rules.

And the backlash has already begun. Quietly, influential creators have voiced fears that such a merger would “tighten a noose” around the film market, shrinking the number of theatrical releases and choking competition, much like what happened after Disney acquired Fox, and the volume of major studio films in cinemas sharply declined. U.S. and EU regulators have already indicated that they intend to scrutinize the agreement intensely, and political voices from both parties — including Republicans like Senator Mike Lee and senior Democrats — are expressing concerns about the deal’s potential impact on market diversity, consumer prices, and artistic freedom. The merger may make sense from an industrial perspective, but it will not be welcomed quietly. Hollywood does not fear change; it fears hegemony. And to many, this deal looks simply too big not to be challenged.

But perhaps the most exposed nerve in this entire story isn’t streaming, nor catalog consolidation, nor even antitrust scrutiny: it’s the movie theater as a physical space. The mere possibility that Netflix could take control of one of the studios that supplied cinemas for an entire century has set off deep alarm bells among exhibitors, directors and distributors. After all, Ted Sarandos has never hidden his stance: for him, a film’s theatrical life can — and should — be minimal. Netflix has never believed in the dark room as an essential stage in a film’s life cycle, but rather as a ritual to be performed almost out of obligation, either to appease filmmakers or to satisfy Oscar eligibility rules.

And although recent years have shown a cautious attempt at rapprochement with the theatrical market, no one inside the industry believes this reflects a genuine ideological shift; at best, it is strategic and situational. For the cinema ecosystem — already strained by shrinking release windows, rising operational costs, dwindling audiences and fewer titles since the Disney–Fox merger — the idea of Netflix gaining control of Warner’s pipeline sounds like an existential threat: what happens if one of the last studios still capable of sustaining theatrical releases is absorbed by a company that does not see intrinsic value in the cinema as a place?

That fear — almost existential in tone — explains the anxious reaction coming from filmmakers, unions and theater owners. It isn’t nostalgia. It’s survival.

And yet, there is an undeniably bright side. Netflix does not view the world from Los Angeles. Its decisions are informed by São Paulo, Seoul, Lagos, Mumbai, Mexico City, and Istanbul. If it takes control of Warner and HBO, what resonates in Brazil may carry the same weight as what resonates in California — perhaps more. This opens the door to truly transnational storytelling, to franchises born outside the U.S.–Europe axis, to a profound shift in the cultural centers of the industry. Hollywood never embraced this voluntarily; platforms did, because their business depends on the world.

Of course, this future carries equally profound risks. Super-catalogues concentrate power, narrow competition, and shrink creative diversity. Regions like Latin America may gain global exposure but lose local autonomy. Mergers of this scale inevitably bring layoffs, centralization, and restructuring that often begins at the international level.

In the end, Netflix’s potential acquisition of Warner is not just a sale. It is a reorientation. A farewell to a model that shaped the 20th century and the arrival of a hybrid creature — part studio, part platform, part technology company — that is poised to shape the 21st. A 28-year-old company poised to take over a 100-year-old studio. The algorithm meets the tradition.

And so the question that remains — and will follow us in the years to come — is both simple and enormous: what stories will survive when the algorithm becomes the new studio? And who will decide which stories deserve to exist in a world governed by global data?

We are witnessing, in real time, the most radical transformation Hollywood has undergone since its own invention. Isn’t that fascinating?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

2 comentários Adicione o seu