Much is said about how the world has changed over the past 25 years, often using the turn of the millennium as a narrative shortcut. But the transformation was real and profound. The so-called Digital Revolution altered everything: how we see ourselves, how we communicate, interact, and consume culture. At the heart of that shift is a platform that began in an almost banal way, mailing VHS tapes, then DVDs, and eventually arriving at what would later be called streaming.

Initially, Netflix was not perceived as a threat. It was born as an outlet.

When streaming began to gain scale, what filled its catalog were not new releases or freshly minted prestige titles. Still, what the traditional system had always treated as surplus: films and series already amortized, older seasons, sitcoms that had ended years earlier — titles that had long since fulfilled their primary function on broadcast TV, pay TV, and home video.

The linear television model always produced excess. There are only 24 hours in a day, fixed schedules, and clear priorities. Programming departments decide what goes on air; production focuses on what comes next; and sales — historically separate — handle the business of licensing “whatever can still make some money.” That is where catalog titles live: old, inexpensive products, useful for closing deals and hitting targets.

Netflix occupied that space perfectly. For studios, it was easy, incremental, low-risk money. A bonus. Friends, The Office, Grey’s Anatomy, ER, films from the 1990s and 2000s, all of it was treated as “residual value,” not strategic value. No one was sacrificing the present; they were simply monetizing the past.

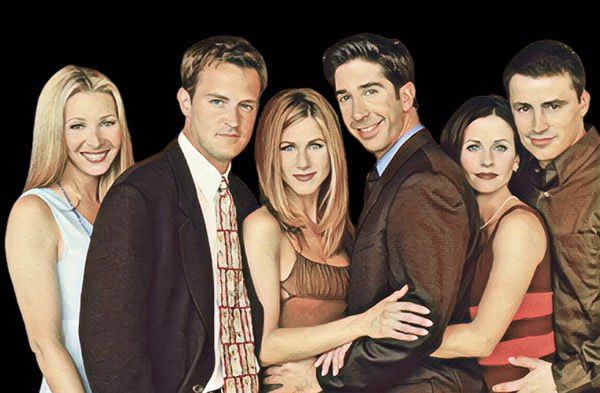

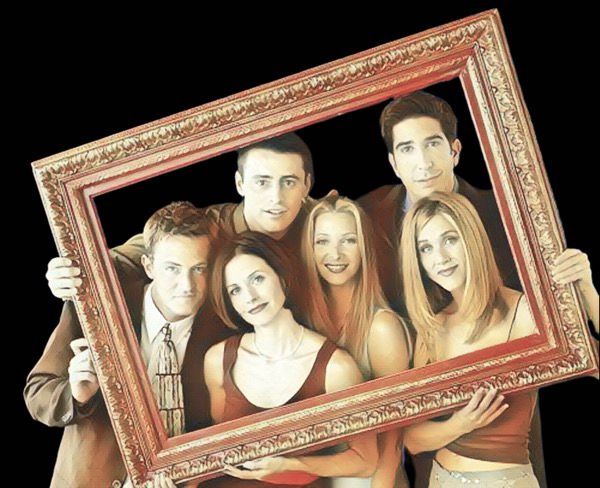

But Friends was never just another catalog title.

Long before streaming, the series had already proven its power as a structural phenomenon. During the golden era of pay TV, when channels fought for leadership down to decimal points, Friends was the engine that propelled Warner Channel to the top. Not only during its original run, but — even more revealingly — after it ended. Its reruns sustained ratings, built loyalty, and kept the channel competitive in any time slot.

Sex and the City played a similar role, it’s true. But Friends always operated on another level. It was not simply a hit series; it was a consumption habit, transversal, universal, and generational. A rare case where repetition does not wear a show down, but strengthens it.

That is why Friends’ resurgence on Netflix came as no surprise to anyone familiar with its history. What changed was the scale.

Because without the constraints of a linear schedule, streaming revealed something the traditional system had never fully measured: the value of permanence. Old series didn’t merely survive outside television; they flourished. They found new audiences, became a shared language, and crossed generations.

And no series represents this better than Friends.

On Netflix, Friends was not just a “classic available to watch.” It was a habit anchor. In 2018, it was the second most-watched title on the platform in the United States, with more than 30 billion minutes viewed in a single year, a blockbuster performance by contemporary standards. Even more telling: a significant portion of that audience was young, many viewers born after the show’s original run had ended.

In other words, Friends was not being revisited. It was being discovered.

For that generation, the 1990s sitcom was not nostalgia; it was daily comfort, emotional shorthand, shared cultural language. Friends taught Netflix something essential: streaming does not survive on novelty alone. It survives on return. On attachment. On repetition.

As Netflix grew, studios looked back and concluded — quite conveniently — that the platform’s success existed because of them. Because of their IPs, their brands, their legacy. The logic was simple, and wrong: we pull our catalog, the audience comes with us.

Thus began the era of proprietary platforms.

Warner, by then under the AT&T umbrella, entered the streaming race, betting on what had always been its most prestigious symbol: the HBO brand. It was a powerful, respected name, forged across both pay TV and broadcast television. But even among its historic successes, one title stood apart for its transversal, popular, enduring appeal: Friends.

When the series left Netflix to “return home,” the move was framed as strategic. But it rested on a dangerous assumption, that the value of the content lay in the IP itself, not in the ecosystem that had once again turned it into a phenomenon.

The mistake became clear quickly.

Habits cannot be transferred by decree. Prestige does not guarantee retention. Audiences do not migrate en masse simply because a title has changed addresses.

While studios pulled their libraries back to reinforce platforms still under construction — and while Warner itself would soon be merged with Discovery — Netflix doubled down. Original production at a global scale. Constant volume. Refined algorithms. Big-name creators. And an international strategy that turned peripheral markets into central ones.

Today, the result is obvious. For younger audiences — especially outside the United States — “streaming” remains almost synonymous with Netflix. The brand comes before the content. Other platforms arrived later, many of them defined in direct opposition to it.

And then we reach the most ironic point in this story.

Five years after Warner pulled Friends from Netflix to strengthen its own platform, the market is now seriously debating the possibility of Netflix acquiring Warner. Not licensing its catalog. Not renegotiating windows. Buying the studio. The legacy. The entire structure.

The symbolism is impossible to ignore.

What began with the removal of one of Netflix’s most significant titles may end with Netflix absorbing the very studio that believed that title would be enough to contain it. This is not merely industrial consolidation. It is narrative.

Would such a purchase be a twist of fate? A patiently awaited revenge? Or simply the historical moment to answer with the same tools once used against it?

For years, Netflix was treated as David — the intruder, the dependent, the disposable platform. Today, it acts like Goliath: buying, incorporating, redefining the field. And century-old studios discover too late that controlling the past does not guarantee the future.

Perhaps Friends was never just a sitcom. Perhaps it was always the warning — ignored, repeatedly — of who truly understood the audience.

In the end, the question remains, now with historical weight: Who was David, who was always Goliath, and when did they switch places?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.