There is no longer any doubt about the starting point of this story: Warner is going to change hands. Discovery has decided to exit the studio and streaming business, formally opened the sale process, and triggered one of the most consequential fights Hollywood has seen in years. This is not a hypothetical negotiation. Offers are real, numbers are public, and the outcome will reshape the entertainment landscape.

In the first phase, Netflix clearly took the lead. It put forward a proposal anchored in cash, with a relatively straightforward integration plan and, most importantly, something Warner has been lacking for far too long: the promise of closure. After years of improvised mergers, restructurings, and strategic whiplash, the Warner board backed Netflix’s offer, and the market largely assumed the outcome was all but settled.

That assumption did not last.

Paramount Enters the Scene

When Paramount stepped forward, the reaction from many observers was confusion. Why now? Wasn’t Paramount itself still digesting a merger? Wasn’t it weakened, defensive, and late to the game?

In reality, the move was consistent — almost inevitable — once you look at Paramount’s trajectory.

Paramount Pictures was founded in 1912, one of the original pillars of Hollywood’s studio system. For decades, it helped define what the industry looked like, shaping stars, genres, and the very idea of the American movie studio. But as the classical system collapsed in the mid-20th century, Paramount was also one of the first majors to lose its status as a “pure” studio.

Through its absorption into larger corporate structures — most notably under Viacom, originally a CBS offshoot that grew by acquiring TV channels like MTV, Nickelodeon, and Comedy Central — Paramount became part of a portfolio-driven conglomerate. The studio survived, sometimes thrived, but no longer sat alone at the center of decision-making. Its symbolic weight remained; its strategic autonomy diminished.

That dynamic deepened over time. After years of fragmentation, Viacom and CBS remerged in 2019, creating Paramount Global. It was not a merger of strength, but of necessity — a way to regain scale in a market increasingly dominated by technology companies. It stabilized the company, but it did not solve the underlying problem.

The real shift came in 2024, when Skydance Media, the production company founded by David Ellison and long-time partner of Paramount on franchises such as Mission: Impossible, Top Gun, and Transformers, took control of Paramount Global. Backed by Larry Ellison, founder of Oracle, and RedBird Capital, the company remained publicly traded and kept its brands, but its center of gravity changed.

The Paramount that emerges from that transition is more aggressive, more comfortable with consolidation, and far more willing to assume risk. That is the Paramount now making a play for Warner.

The Bid and the Politics Around It

Paramount did not enter quietly. It launched a hostile, all-cash offer, going directly to Warner shareholders, offering a higher headline price than Netflix and openly challenging the Warner board’s judgment. It criticized the valuation underpinning the Netflix deal, downplayed the worth of the linear TV assets left behind, and reframed the contest as a question of market concentration.

Politics quickly entered the picture. There is no formal role for Donald Trump in the transaction, but the connections are real. Part of Paramount’s financing includes Affinity Partners, the investment fund run by Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, along with Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds. At the same time, Trump has publicly voiced concerns about concentration in streaming, explicitly naming Netflix as a potential antitrust problem.

None of this determines the outcome by itself. But it raises the regulatory noise level — something Paramount is clearly counting on as it tries to reopen a decision that had appeared settled.

Paramount Today: Strengths, Stars, and Fragilities

To understand why Warner matters so much to Paramount, it helps to look at what Paramount is right now.

In recent years, the company has relied heavily on two creative anchors.

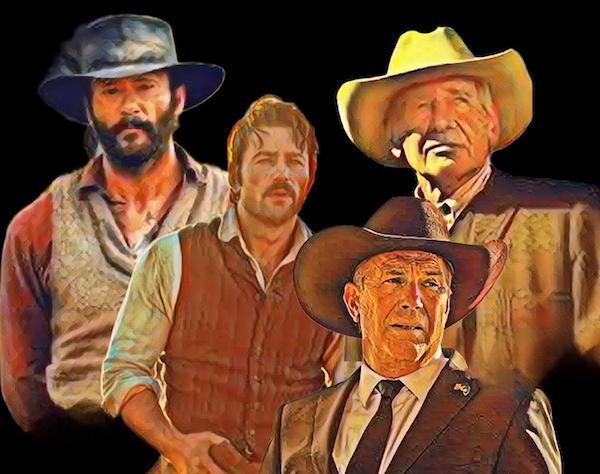

One is Taylor Sheridan. The Yellowstone universe — 1883, 1923, Mayor of Kingstown, Tulsa King, Lioness — became the backbone of Paramount’s scripted output, powering both linear television and Paramount+. Sheridan delivered reliability, volume, and a fiercely loyal audience, particularly in the U.S. But that success also created dependence. With Sheridan now effectively on his way out or at least shopping for new deals, Paramount faces the loss not just of shows, but of the creative axis around which much of its strategy revolved.

The other anchor is Tom Cruise. Paramount remains one of the last studios with a stable, productive relationship with a global movie star who still opens films theatrically. Top Gun: Maverick was not just a hit; it was proof that Paramount could still mount true cinematic events. Alongside Mission: Impossible, Cruise keeps the studio’s blockbuster identity alive. But this strength is narrow. It rests on a small number of projects and a single, exceptional figure.

Beyond those pillars, Paramount’s IP portfolio is valuable but uneven. In film, it has Mission: Impossible, Top Gun, Transformers, and Star Trek. In television and streaming, it holds long-running brands like NCIS, CSI, Survivor, and SpongeBob SquarePants — the latter one of its few genuinely global, multigenerational franchises. There is real value here. What’s missing is breadth and density.

What Paramount Gains From Warner

This is why Warner is so strategically attractive.

Warner offers what Paramount cannot build quickly: depth of catalog, cultural authority, and structural balance. DC, Harry Potter, HBO, decades of premium television and film, enduring relationships with top-tier creative talent — these assets do not simply add volume. They change perception and power.

A Paramount–Warner combination would dilute Paramount’s current dependence on a handful of stars and creators. Tom Cruise would coexist with Batman. Yellowstone would no longer carry the symbolic weight alone, sharing space with Game of Thrones. In theory, risk would be spread rather than concentrated.

There is also a defensive logic. If Netflix absorbs Warner, Paramount risks becoming structurally too small in a market that increasingly rewards scale. Buying Warner is not just about growth — it is about not being left behind.

The paradox is obvious: what Paramount gains — scale, legacy, and symbolic stability — comes at the cost of pushing Warner into yet another complex reorganization.

What Is Worse: NetWarner or ParaWarner?

This is where the question shifts from price to consequence.

Netflix + Warner (NetWarner) is financially clean. There is cash, global scale, and clear leadership. The risk is concentration. An industry more tightly orbiting a single technology company, with long-term implications for competition, creators, and regulation. NetWarner is potentially worse for the market as a whole.

Paramount + Warner (ParaWarner) eases that concentration fear, but introduces another danger: execution. Two companies with long merger histories, distinct cultures, and heavy legacies stitched together yet again. The risk here is not monopoly, but fatigue — another prolonged cycle of integration that Warner, in particular, seems desperate to escape. ParaWarner is potentially worse for Warner itself.

Put simply, NetWarner is unsettling because of how big it becomes. ParaWarner is unsettling because of what it sets in motion.

What the Bets Suggest

Right now, the market is betting on NetWarner. Not because it is ideal, but because it is predictable. There is a signed deal, board approval, and a clearer integration path. Regulatory scrutiny is real, but widely seen as manageable for a company of Netflix’s scale and experience.

ParaWarner requires many stars to align at once: shareholders overriding the board, regulators significantly obstructing Netflix, and flawless execution by a group still adjusting to new control under Skydance. It is possible — but less likely.

At its core, this is not about the most elegant solution. It is about the least destabilizing one. After years of permanent transition, predictability has become a form of value for Warner.

The fight is ongoing, the billions are still on the table, but the fault line is clear. This is no longer only about who gets Warner — it is about who gets to define how this chapter of Hollywood’s history ends, and at what cost.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.