I only watched The Beatles Anthology now, even though it arrived on Disney+ back in November. Perhaps not by chance. Some works require the right moment, and this is one of them.

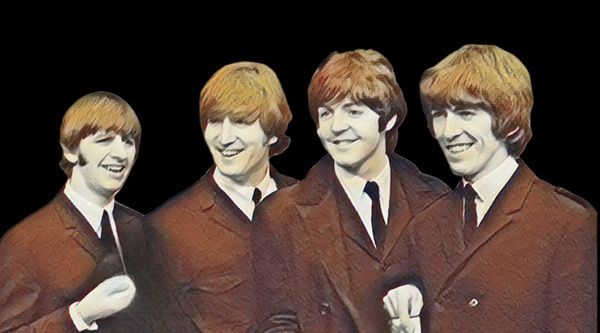

I belong to the generation of the children of those who turned the “four boys from Liverpool” into legends and myths. I was born already surrounded by boomers who would lose all restraint when they talked about, listened to, or sang Beatles songs. I always liked them. Their music was everywhere: at family gatherings, on old radios, on inherited records. But for many years, I confess, I never fully understood what made them gods among humans.

Perhaps because, even after so many decades, that question remains open. There are countless films, books, interviews, and documentaries attempting to decode the phenomenon — and still the world wants more. It’s no coincidence that there is now enormous anticipation around Sam Mendes’s ambitious Beatles film project, currently in production, which promises to tell the band’s story through four interconnected films, each from the point of view of one member. The announced cast is impressive: Paul Mescal, Barry Keoghan, Joseph Quinn, and Harris Dickinson, with a planned release in 2026. Even after everything that’s already been said, we are still trying to understand.

The problem is that these narratives almost always repeat themselves. The story repeats. The images repeat. The anecdotes repeat. Everything is said — but rarely explained. Beatlemania is presented as a phenomenon, not as a process. As if it were a sudden flash, an inexplicable collective miracle.

And it wasn’t.

When they became astronomical, it didn’t happen overnight. Before they were myths, they were already friends. Before they were an industry, they were already a band. Before they were a global phenomenon, they had accumulated nearly ten years of invisible road: Liverpool, Hamburg, sleepless nights, precarious stages, near-military discipline, an immense repertoire, musical training forged through improvisation and endurance. The explosion was fast. The construction was not.

Perhaps the greatest strength of The Beatles Anthology lies precisely here: it dismantles the myth to reveal the process.

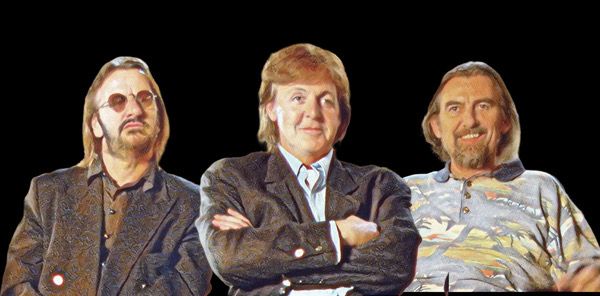

Anthology was conceived in the 1990s, at an emotionally delicate moment in the band’s history. Decades after the breakup — after lawsuits, resentments, prolonged silences, and wounds that never fully healed — Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr finally decided to revisit everything together.

This was not merely a memory project. It was a political, artistic, and emotional gesture: to reclaim their own history from the hands of others. For years, critics, biographers, journalists, and fans told the Beatles’ story for them. For the first time, the Beatles themselves took control of the narrative.

Anthology was conceived as a total project: a documentary series, books, records, archives, and unreleased music. Not to fuel nostalgia, but to organize the past, give meaning to the chaos, and reposition each of them within their shared story. For the first time, the three sat together not to debate contracts or rights, but simply to remember — and to remember each other.

There is something profoundly human in that gesture. This is not just a reunion of musical giants. It is the reunion of three men who were far more than bandmates. They were young people who grew up too fast, endured more pressure than any group before them, made mistakes, hurt one another, and drifted apart, and yet, they survived.

At its core, Anthology is a ritual of reconciliation with one’s own past.

It is no coincidence that the most symbolic gesture of the 1990s emerged from this process: the three returned to homemade demos recorded by John Lennon in the 1970s and turned them into complete songs. “Free As a Bird” and “Real Love” are not merely posthumous releases. They are attempts to close circles. To sing with someone who is no longer there. To artificially extend a time that life itself interrupted.

Once again, the Beatles were ahead of their time. In a world that was only beginning to debate archives, memory, and legacy, they were already doing it on a monumental scale — decades before such conversations became common.

Yesterday, December 8, marked 45 years since the death of John Lennon. For a generation born amid the obsession with a Beatles reunion, that December 8, 1980, was not just a tragedy — it was the gunshot that killed a global hope: the dream of seeing the four friends from Liverpool together again.

Lennon’s death, premature and still inexplicable at just 40 years old, ended something that every subsequent film and documentary — including Anthology itself — continues to pursue: the recovery of the friendship and love that bound together the band that defined rock, marketing, pop culture, and modern celebrity in the 20th century. More than that, it prevented a public reconciliation between Lennon and McCartney — a conversation the world was still waiting to witness.

That absence explains a great deal. It explains the endless reissues, the constant return to archives, and even why, decades later, projects like Sam Mendes’s Beatles films are still being made — as another collective attempt to imagine what history did not allow to happen.

Perhaps that is why The Beatles Anthology only makes full sense now.

Because it does not simply explain how the Beatles came to be. It explains what happens to people when the world turns them into legends too early. It shows talent, yes — but also insecurities, vanity, conflict, misalignment, exhaustion. It humanizes the myth without diminishing it. On the contrary, it enlarges it.

The Beatles are so singular that, more than 50 years after their breakup, the world still wants to know more: more about the music, the fever, the moment of discovery, the friendship, the fights, the fractures. Anthology was meant to be the final word, released just a few years before George Harrison’s death. And once again, it is revealing how the band was — and remains — radically different from anything that came before or after.

Today, I understand better why they were treated like gods. Not only because of the music — which alone would be enough — but because there has never again been such an absolute convergence of talent, timing, youth, cultural rupture, and global impact.

Seen today, The Beatles Anthology is not a memorial. It is a reckoning with history. And perhaps, above all, a gentle reminder that behind every legend, four boys from Liverpool just wanted to play — and ended up changing everything.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.