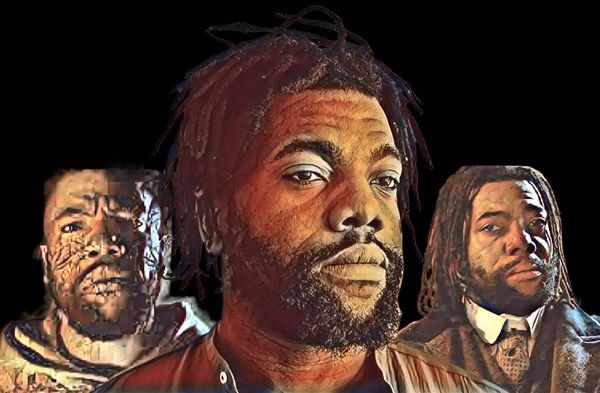

There is a rather simplistic rule — one I may have invented myself — that suggests a great drama depends more on a well-crafted villain than on its hero. And Down Cemetery Road delivers one of the most unsettling antagonists television has offered in years, thanks to the work of Fehinti Balogun.

That is because there are actors who arrive on screen carrying more than just a character, and Balogun is one of them. His work — whether in film, television, or on stage — never stops at serving the immediate needs of the narrative. He performs with an awareness of presence, understanding that a Black body on screen is, in itself, still a political statement.

British and the son of a Nigerian mother, Balogun grew up in the United Kingdom, shaped by the lived experience of the African diaspora. That background — cultural, political, and emotional — informs his worldview and explains why race, belonging, and inequality appear in his work not as abstract themes, but as embodied realities. Before making his mark in film and television, he trained in British theatre, developing a physical and intellectual approach to acting — attentive to the body, to silence, and to listening — that continues to define his screen presence.

Balogun is known to wider audiences for Dune, I May Destroy You, A Gentleman in Moscow, and most recently Down Cemetery Road. But to reduce his trajectory to acting alone would be to miss a crucial layer of what he builds. His career is shaped by an ongoing dialogue between art, activism, and identity. Whether portraying a deeply unsettling antagonist or creating a hybrid work like Can I Live?, he consistently returns to the same fundamental question: who gets to speak, who is heard, and who pays the price of silence?

That intersection became even more evident during his visit to Brazil in 2023, when he presented Can I Live? and took part in discussions on climate emergency, racial inequality, and the lived experiences of vulnerable communities. The exchange highlighted how deeply his work resonates with global realities — especially in the Global South, where climate, race, and class are inextricable.

The villain who destabilises the centre of the frame

In Down Cemetery Road, Balogun plays Amos Crane, a character who could easily fall into the trap of the functional villain — and only avoids it because he is not merely a threat, but a form of lethal discomfort. His presence reshapes the rhythm of the series, generating physical and psychological tension that keeps the viewer perpetually off balance.

Nothing about Amos is excessive; everything is measured. Balogun crafts the character through restrained gestures, subtle shifts in register, and an unsettling calm capable of turning even silent scenes into moments charged with electricity. Opposite Emma Thompson and Ruth Wilson, he does more than hold his own as an antagonist — he expands the dramatic range of the protagonists themselves, a rare feat that speaks to his artistic maturity. The train journey to Scotland, in which he and Thompson barely exchange a word yet communicate everything through their gaze, stands as one of the most chilling and accomplished sequences on television in recent memory.

Art as a translation of inequality

That same precision reverberates beyond conventional fiction. Can I Live?, Balogun’s self-authored project blending music, spoken word, and documentary, emerged from conversations with his mother and a generational clash over activism and survival. The work reframes the climate crisis as a lived experience, exposing how environmental injustice disproportionately affects Black bodies and historically marginalised communities.

Balogun does not speak of climate change as a distant abstraction, but as an urgent, present reality. Colonialism, capitalism, and institutional neglect appear not as closed chapters of history, but as active structures shaping today’s crises. His art becomes a sensitive translation of debates that often remain inaccessible or overly technical.

As one of the founders of Green Rider, Balogun also works to transform environmental practices and power structures within the audiovisual industry, advocating for a more ethical and sustainable system. For him, meaningful change is not merely technical, but cultural — requiring a reassessment of how consumption, status, and human value are defined.

The future he points toward

The season of Down Cemetery Road concludes to considerable acclaim, much of it rightly centred on Fehinti Balogun’s contribution. Moving between major franchises, author-driven series, theatre, and activism, he is shaping a career driven less by visibility than by impact. His trajectory suggests a possible path for contemporary audiovisual culture — one in which entertainment, social awareness, and aesthetic responsibility coexist without cancelling each other out.

In an industry still prone to turning diversity into surface-level discourse, Balogun offers something far more demanding: representation with consequence.

And that, in the end, is what makes him so impossible to ignore.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

1 comentário Adicione o seu