As published in Bravo Magazine

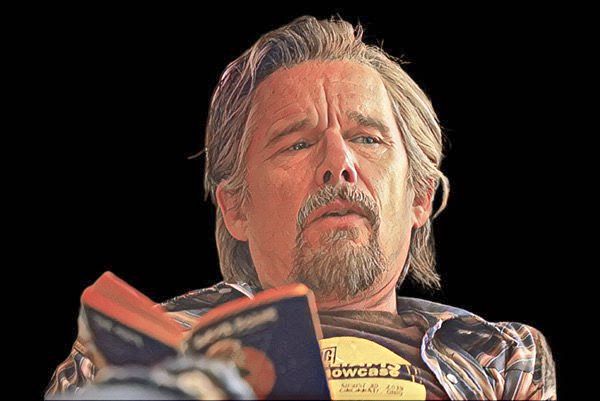

Ethan Hawke is one of those artists who move through decades without ever settling into comfort. Actor, director, writer—restless by nature—he has always orbited projects that treat cinema, and now television, as tools for moral, political, and human reflection. Sterlin Harjo, in turn, emerged as one of the most important names in the new American television when he co-created Reservation Dogs, a groundbreaking series that placed Indigenous characters, writers, and directors at the center of the narrative, with humor, pain, affection, and identity. The production became a cultural landmark and accumulated awards, critical acclaim, and an influence that can already be clearly measured.

The two met even before working together on Reservation Dogs. A mutual friend introduced Hawke to a script by Harjo that Hollywood had rejected precisely because it was told from an Indigenous point of view. The connection was immediate. Conversations followed, collaborations, Hawke’s participation in the series that would change Harjo’s career—and now their partnership reaches another level with Hidden Truth, a contemporary noir set in Tulsa, where truth, memory, local politics, and personal obsession intertwine in an uncomfortable and deeply human way.

In The Lowdown, Hawke plays Lee Raybon, the owner of a used bookstore and a citizen journalist who calls himself a “truthstorian.” The character is loosely inspired by Leroy Chapman, a journalist Harjo worked with in Tulsa: a reporter who drove an old white van through the city, made videos in the name of truth, did not care about money, and took pride in being a thorn in the side of the local establishment. It was Leroy who, after watching one of Harjo’s short films, urged him to leave behind his journalistic videos and fully embrace his path as a filmmaker—a gesture of generosity Harjo describes as decisive in his own trajectory.

In the series, Lee investigates powerful figures in the city and, in doing so, awakens forces that would rather remain buried. The Lowdown premiered in the United States on FX and will arrive in Brazil on Disney+ in December under the title Hidden Truth, reinforcing the platform’s investment in prestige, auteur-driven drama.

In a conversation with Bravo magazine, Hawke and Harjo spoke about Tulsa as a character, the crisis of journalism, the role of art in times of polarization, and the solitude that runs through the protagonist. Below are the main excerpts from the conversation.

BRAVO: You created a noir story deeply rooted in Tulsa, which almost feels like a character itself. What was most important to you in capturing the city’s atmosphere and weaving its history and community into the heart of the series?

Sterlin Harjo: Well, I think that’s exactly the key: it had to be about a community. I mean, even though it’s about Lee, just like in Reservation Dogs, it’s actually about this community of people that surround Lee. And it’s about how they feed his curiosity and get him out of bed every day. You know, it’s like, ‘I’m gonna go visit Cyrus, aka Killer Mike, I’m gonna go visit him.’ He’s telling the truth in his own way, and he’s also trying to fix his part of the community through what he does. And it’s these little things, this tapestry of things that I think Lee collects these people who are trying to make a difference. They’re all kind of like him, you know? I think even his daughter, they’re all kind of versions of him. And that’s who he wants around him. And I do the same thing. I mean, it’s me. I like to ‘collect’ these people who, like Ethan, who to me is someone who is an artist. And that’s why we can talk about music, art, books, and all these things. And I try to surround myself with these people because it makes me do what I do better. And I think Lee does that in a way. So showing Tulsa was showing the city through the eyes of the whole community—not just through politics, not just the white community, not whatever. It was showing the whole thing.”

Ethan Hawke: And what I love about that question is that I’ve been hearing, as people watch the show, how much they say they can smell the city, feel Tulsa. And Tulsa is a character. Tulsa is my co-star. And all the credit goes to the production design team. And part of the fun of being on the set of Reservation Dogs happened again here, which is the fact that all these people are Sterlin’s friends. They’re people you care about. They’re people you have a history with. So you can say, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be cool if that poster were on the wall?’ Or, ‘Oh, that’s too clean,’ or ‘that’s not clean enough,’ or ‘that wouldn’t be like that.’ And that way, every time I walk onto the set, I’m walking into a real environment. It’s so easy to act well when the set and the atmosphere around you smell real. When you have to manufacture all the drama because what’s around you is fake, that’s a much heavier weight to carry. And the team around you is just fantastic.”

Sterlin: Yeah, I mean, I can’t praise them enough. All the reviews that say it ‘feels lived-in,’ whether it’s the costumes, hair, and makeup, or the sets… all of that is because everyone is extremely grateful to be working and doing what they’re doing. There are shows I watch, and I think, ‘This could have been done anywhere and with anyone; all the clothes look brand new, never worn.’ Here, it’s the opposite. Everything is lived-in. Everything is about the story. It’s almost as if they’re all journalists themselves, trying to get to the bottom of the characters. They approach every character and every scene that way.”

BRAVO: Today, the world seems to resist the truth. How do you see journalism in this scenario of information overload and constant noise?

Ethan Hawke: I’ll start because I’m really grateful for this question. One of the things we didn’t foresee with the internet was the effect it would have on journalism. The idea of giving everyone a voice online seemed very noble—free education, equal opportunity—but it created a destructive force we didn’t anticipate, which is a kind of Tower of Babel: all voices talking all the time, and the chaos that creates. It’s impossible not to think about movies like All the President’s Men. There was a time when being a journalist was seen as honorable and as an essential safeguard of society. They took that very seriously. And I love that, right in the opening scene, you see in Lee a pride in being an old-school journalist: ‘We fact-checked this,’ ‘I went through it line by line,’ ‘we stayed up for three nights.’ He doesn’t just want to go online and write, ‘Donald Washburg is a bad guy.’ He wants to prove it. Today, it’s very hard for both people in power and people without power to understand how the truth is being manipulated. When big money is at stake, people don’t like the truth to come out, even when it would actually be in everyone’s best interest. A lot of people today get their news from people who are not journalists, and it comes as gossip. That’s always existed, but now it has taken on a different dimension. And we did not realize before how essential a Don Quixote figure like Lee Raybon is for the conversation we need to be having today. We feel very grateful to be releasing this show right now.

Sterlin Harjo: Sometimes we look at journalists, and it almost feels like a superhero putting on a cape. But we’re in a period where we see everything now, you know? We’re just normal people. And journalists are too. And I think showing—telling the story of a real person, like, this is a journalist—it’s not ‘I come in here, I’m in the newsroom, and I’ve got my hot stories.’ It’s not really like that anymore. But the idea of being a journalist is still the same. It’s about telling the truth. It’s about finding the truth. It’s about reporting to people and trying to give them something accurate so they can live their lives after receiving that news and try, you know, to move forward, to live, to survive.

It’s a very simple thing. And I think it appears in many different ways, but there’s something really—I don’t know, I didn’t imagine it would be so attractive to him, just taking that on.”

BRAVO: Tulsa carries a painful past. What does it symbolize within the series?

Sterlin Harjo: I think Tulsa, in general, and places like Oklahoma, tend to be overlooked. And the show talks about the nuance of the human experience and also the nuance of places like Tulsa, and for me, it represents the whole United States. Tulsa is a Native word; it’s a Muskogee Creek word that comes from ‘Tallahassee.’ I think that’s something big to talk about in a TV show about someone getting beaten up for the truth. But it’s all in there. In the end, that’s what it’s about: healing through truth, fighting for the truth, and the idea that truth is something noble to fight for.

Tulsa represents so much of what the United States is: racial history, Indigenous history, forced displacement, and erasure. It’s a city that carries deep wounds. At the same time, it’s going through a movement of trying to heal by facing its own history head-on. Hidden Truth talks about that: healing through truth. Telling the truth is still an act of courage.

Ethan Hawke: All of that was beautifully said, and all of it is true. But it’s also told through Sterlin’s eyes, which are incredibly funny and full of love, wit, peculiarity, and the strangeness of how weird we all are. One of the first things my character says is that he calls himself a ‘truthstorian.’ What I love about that word is that it brings truth and history together. If we’re not standing on firm ground, we don’t know where we are or where we’re going. At the same time, it’s not really a word; it doesn’t quite make sense, and it’s hard to say. Which is very much like Lee himself. He’s a hot mess who means well. And that’s what drives the heart of the show.

BRAVO: After working on a series like this, do you still believe in the transformative power of art and journalism?

Ethan Hawke: I know they do. One of the things I can point to very quickly is this: there’s a reason why authoritarian governments, whenever they want to assert their power, try to dominate the arts. It’s a way to shut down conversation. This happens throughout history. It’s a go-to move.

I’ve always believed that the artistic community and the intellectual community represent the mental health of a society. And when it’s free and expressive, not afraid of new ideas, looking at its past and its future, and there’s a lot of light in it, you have very good mental health. When that darkens, huge blind spots begin to appear in a country’s mental health. So I just know it’s powerful. I’ve seen it in my own lifetime. In a small way, I feel art has been hugely responsible for the decrease in homophobia throughout my life. When I was a kid, homophobia was extremely intense. And I see my children growing up without that level of fear, discomfort, and hatred of others that was imposed on me as a young man. And I think a lot of that has to do with literature, movies, and people talking. Why that hasn’t happened in other places is a longer conversation. But you see the effect on people’s hearts and minds when we have a good mental health story, so to speak.”

Sterlin Harjo: Yeah. I’m a Native filmmaker. We’ve been here a very long time as Native people. I’ve been doing this for over twenty years now. And there were many moments when it felt like our voices were never going to be heard. There were very serious conversations about how to break through, how to do this. It felt like there was no way, like nobody cared. I was in Hollywood meetings where I heard, ‘Native movies don’t sell, we can’t fund your film.’ And that felt very dark.

But Reservation Dogs got made, you know? It happened. And it keeps happening, over and over. There are dark periods, yes. Journalism is a very tough place to be right now. But it’s going to come out of that, and it’s going to help lead us. And the arts will also keep leading us, because they have to. That’s what they’re there for.

BRAVO: The series deals a lot with the protagonist’s solitude. How was that approached?

Ethan Hawke: I think, strangely, Lee’s obsession with literature and with the importance of expressing ideas—the idea that expressing ideas is something valuable communicates someone who is in touch with their own solitude and comfortable with their own solitude. You’re absolutely right: that’s why fiction is a different art form, because it’s such a private art form, while audiovisual work is… I keep thinking about a lot of different things. It’s a very hard question.

Sterlin: I think he’s also creating a life through community, again. Because he’s not necessarily alone: he has Cyrus, and he has… he doesn’t have to… he has the Native security guard.

Ethan: He’s uncomfortable being alone, you know? He likes to have people around. And that also communicates solitude, in a way. He’s afraid of being alone. But there are these wonderful shots of Lee in his apartment, which I really love, where you feel like he spends a lot of time there.

Sterlin: And I think, you know, Ethan and I are both fathers, and we sort of co-parent. So there are times when your kids are with the other parent, and that’s a lonely time, you know? And Lee kind of distracts himself by working on his obsessions. I think that’s part of it, too. And also, I did talk to Leroy’s family, answering that earlier question: we were in communication, they’re in the show, many friends are in the show, and many of his things are in the show too. So that acknowledgment is there.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.