Murder in Monaco starts from a case that has never ceased to fascinate: the deaths of Lebanese-Brazilian billionaire banker Edmond Safra and his nurse Vivian Torrente in 1999, inside an ultra-secure apartment in Monaco. All the elements were there for a rigorous documentary about power, paranoia, human error, and the limits of extreme security. What Netflix delivers, however, is something else. As usual.

The film clearly belongs to the “Netflix brand” of true crime, where narrative takes precedence over commitment to truth. Not by inventing facts, but by rearranging, inflating, and relativizing them to keep viewers in a constant state of suspicion, even when the justice system has already answered the central questions of the case. Director Hodges Usry, however, has a surprising twist up his sleeve.

A crime explained and artificially reopened

The essential facts are well known. The fire that killed Safra and Torrente was small, starting in a wastebasket. It should not have been fatal. What killed them was panic. Convinced by one of his nurses, an American and former member of U.S. Special Forces, that armed intruders were inside the apartment, Safra locked himself in a panic room and refused to open the door to firefighters. The false threat delayed rescue efforts and sealed the outcome.

The author of that lie was Ted Maher, who confessed to starting the fire to stage a heroic rescue and was convicted in 2002 of arson resulting in death. None of this is new. None of it is legally controversial. Still, Murder in Monaco behaves as if everything were unresolved because Ted himself becomes the narrator, convincingly selling the story of the wrong man in the wrong place, falsely convicted of a crime he did not commit. As an American accused and sentenced by foreign authorities, his account gains an aura of manufactured controversy. It is a version that Hodges Usry embraces as truth, leading the audience for over an hour through a series of accusations that reinforce Maher’s narrative. Until…

The problem is not raising doubts, but who raises them

The documentary chooses a dangerous path. The story is driven by the very person found guilty by the courts, not as an object of critical examination, but as an emotional guide. From there, the script favors twists, eccentric interviews, and conspiracy theories, many of them already dismissed by official investigations and presented without balance.

Figures who never managed to substantiate their accusations in court are given space to suggest plots involving the mafia, governments, financial interests, and, in fact, most insistently, the widow Lily Safra. All of this unfolds with no real commitment to evidence, contradiction, or rigorous context.

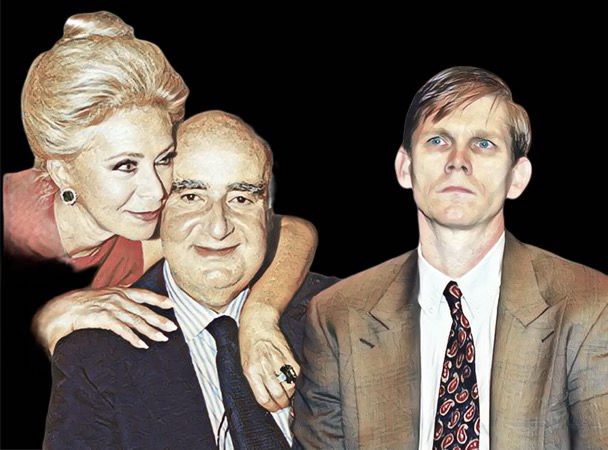

Lily, a Brazilian woman who was already wealthy when she married Edmond, is treated with insinuation. The film highlights that she had been married four times and mentions the suicide of a former husband in terms meant to sound suspicious, including the detail that he took his own life with two shots to the chest. She was never well regarded by Edmond’s brothers, who do not appear in the documentary but whom a friend claims suspected her involvement in the bizarre circumstances of his death. With no concrete facts, the conspiracy narrative borders on defamation.

The result is unsettling. Serious accusations are treated almost as entertainment. The film toys with conspiracy, adopts the tone of a thriller, and leans into shock value, even though what is at stake is the real death of two people.

Action-movie pace, fictional responsibility

There is no denying it: Murder in Monaco is slick. The editing is efficient, interviews are cut for impact, and the twists work. At times, the documentary plays like an action or espionage film. Almost “fun.” Until the final reveal.

After escaping prison in Monaco, being recaptured and serving more than half his sentence before being deported to the United States, Ted Maher once again becomes the center of an implausible story.

In the final fifteen minutes, after insinuating involvement by Lily Safra and even the Monegasque royal family, Ted, now living under the name Jon Green, is revealed to have accumulated a new list of legal troubles in the U.S. From car theft to being charged with conspiring to murder his own new wife through a hired hitman, he was imprisoned again and is currently serving a sentence until 2031 in Texas.

At this point, Hodges Usry steps in as narrator and character, attempting to defend his own documentary. He claims to have devoted four years of his life to the project, yet the research proves fragile. Ted lied about having been in the military and continues to insist on his innocence. His first wife, Heidi, who appears in archival footage from the time when she believed in his story, changed her position after he escaped from the Monaco prison, cut ties with him, and disappeared from public view with their children. The documentary suggests she may have been bribed by Lily Safra rather than showing that she reached a settlement after legal action. Since Heidi declined to participate in the film and Lily died in 2022, their perspectives remain unheard.

And that is where the real problem lies.

We are dealing with a real crime, a concluded investigation, people who died, and others who continue to live under recycled suspicions. The light tone, frantic editing, and constant appeal to mystery turn all of this into spectacle. The film merely reenacts old doubts to keep viewers engaged for nearly two hours and, by the end, admits that it too was misled and continues to mislead its audience.

Emptiness as a strategy

Worse than revisiting a closed case without presenting any meaningful new evidence is the documentary’s own admission, in its conclusion, that its research is flawed. This may work dramatically, but it is weak and ethically questionable.

The tragedy of Edmond Safra does not become more complex when wrapped in narrative smoke. On the contrary, it loses clarity, gravity, and humanity.

In the end, the documentary says far more about the limits of contemporary true crime than about the crime it claims to investigate. When storytelling outweighs truth, mystery stops being a tool for reflection and becomes just another product.

And yes, Jon Green, or Ted Maher, is in prison. But who is he, really? Not even that question does Murder in Monaco dare to investigate. Shouldn’t that have been the obvious place to start?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.