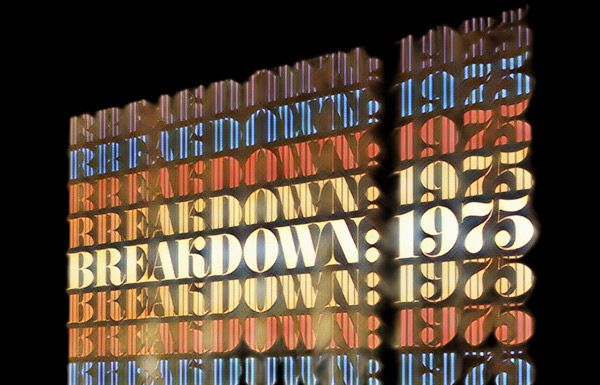

The Netflix documentary about 1975, narrated by Jane Fonda, is far more interesting—and far more honest—than the slogan that accompanies it. By claiming that it was “the greatest year in the history of cinema,” the film provokes, simplifies, and exaggerates. But once that promotional hook is set aside, what the documentary actually offers is something more sophisticated: a consistent reading of how art, politics, and industry converged at a point of rupture, and how that convergence helps us understand not only the cinema that followed, but the world we inhabit today.

My disagreement with the absolute label does not invalidate the central diagnosis. On the contrary. The documentary is precise in treating 1975 not as a technical or narrative peak— that distinction still belongs, in my view, to 1939— but as a year that crystallized a moral turning point. Hollywood was emerging from the trauma of Vietnam, the institutional collapse exposed by Watergate, and a profound erosion of trust in authority and official narratives. This mood doesn’t appear in the films as an explicit thesis, but as atmosphere: exhausted characters, corroded institutions, endings that refuse comfort.

The choice of Jane Fonda as narrator is anything but incidental. Her voice carries exactly the symbolic weight this story requires. Not only because she was one of the most politically engaged figures in Hollywood at the time, but because her own trajectory embodies the collision between entertainment, activism, and conservative backlash. She doesn’t narrate 1975 from a distance; she is part of the conflict the film examines.

The documentary succeeds in placing very different films side by side as expressions of the same historical unease. The birth of the modern blockbuster does not appear in opposition to political cinema, but in tension with it. Jaws turns diffuse, invisible fear into spectacle, echoing a society no longer sure where the threat lies. Dog Day Afternoon transforms a robbery into a political and media performance. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest puts institutional authority on trial in a country that had just awakened to the realization that its leaders had been systematically lying.

The retrospective gaze is where the film becomes most powerful. By revisiting 1975, the documentary isn’t simply celebrating classics; it is reading the present through the lens of the past. The politicization of everyday life, the centrality of media, the conversion of conflict into spectacle, and the structural distrust of institutions are all there, in embryonic form. The difference is that, at that moment, Hollywood was still able to metabolize these tensions into complex, ambiguous, adult narratives.

Understanding who is behind the camera helps explain this balance. The documentary is directed by Morgan Neville, one of the most consistent voices in contemporary American documentary filmmaking when it comes to culture as a social mirror. Neville is neither an academic film historian nor a pure essayist; his interest lies in moments of transition, when systems begin to creak. In earlier work, he has shown a keen ability to use seemingly “safe” figures, eras, or movements as gateways to broader discussions about power, industry, and collective sensibility.

That approach is fully evident here. Neville doesn’t try to definitively prove that 1975 was “the greatest year in history.” The year functions as a character, as a point of cultural boiling. His cinema is narrative-driven and accessible, but never shallow: the critique is embedded, not underlined. He trusts that viewers arrive through the provocation of the title and stay for the density of the connections he proposes.

There is also a quiet irony that the film handles with intelligence. 1975 marks both the height of this creative freedom and the beginning of its erosion. The industrial success born in that moment reorganizes Hollywood and prepares the ground for a system increasingly driven by numbers, less tolerant of authorial risk. The same year that consecrates audacity also, paradoxically, starts to limit its space.

For that reason, the documentary works best when understood not as a historical ranking, but as an essay on cycles. It starts from the premise that cinema reacts to the world—and that in moments of political and social upheaval, art tends to become more uncomfortable, more political, more revealing. In that sense, 1975 is not “the greatest year in history,” but it is a disturbing mirror: a moment when Hollywood chose to look at the country without makeup—something that, half a century later, we are still trying to do.

Recommendation: very much worth watching. Not because of the exaggeration of its title, but because of the clarity with which it connects cinema, politics, and the present.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.

2 comentários Adicione o seu