There are films that age as documents. And there are films that age as prophecies. Dog Day Afternoon (1975) belongs to the second category: the more time passes, the more it feels as if it was made “for now,” for an era in which every incident becomes a broadcast, every conflict becomes a battle of versions, and everyone — police, press, crowd, even the hostages — is pulled into the same involuntary theater.

Fifty years later, the film’s power isn’t only in its dramatic nerve, its razor-sharp editing, or the near-tactile realism of Sidney Lumet’s direction. It lies in how it captures a cultural turning point. The robbery is the starting gun. What the film examines is the transformation of crime into a public event, the crowd’s moral confusion, and intimacy exposed under the heat of a “dog day,” when the city seems to stick to your skin and life has no soundtrack to organize the chaos.

The true story: when life already looked like a movie — and the press understood it immediately

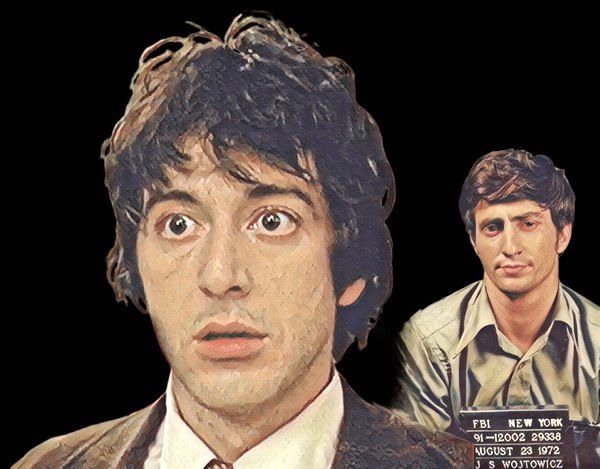

What we see on screen comes from a fact: on August 22, 1972, John Wojtowicz and Salvatore Naturile attempted to rob a Chase Manhattan branch in Brooklyn. The plan starts wrong, falls apart fast, and turns into a long hostage standoff, negotiations, a crowd in the street, television on the scene, and a brutal ending at the airport. It’s the kind of case that, even without a film, already exists as a ready-made narrative — with twists, unforgettable side characters, and a protagonist whose desperation is both clumsy and strangely moving.

The Life piece that recorded it, “The Boys in the Bank,” didn’t just describe the event; it identified something crucial: there was a story of performance there. There was the would-be robber who, cornered, has to talk — and by talking, begins to conduct the crowd. There was a public that, faced with a standoff, chooses to root as if watching a game. There was a negotiation that stops being “only” negotiation and becomes language: gestures, slogans, moments that catch fire. Real life, that day, was already rehearsing the kind of spectacle our century has made routine.

How the film came to be: rights, script, and the decision to tell it “from inside” the heist

Martin Elfand saw the potential in the article, brought it to Martin Bregman, and the project began to take shape within a model typical of 1970s American cinema: take a recent, still-burning true story and build a dramatization that isn’t a mere illustrated reenactment, but an interpretation.

Frank Pierson’s screenplay makes a choice that defines the film: it centers the story around Wojtowicz — in the film, Sonny Wortzik — and refuses to turn the case into a conventional cops-and-robbers thriller. The core isn’t “how to catch him,” but “what this situation does to people.” The script grows out of research, interviews, tapes, and Pierson’s difficulty in “defining” Sonny, because each witness described a different man. What links those versions, in the end, is the same sensation: Sonny overpromises, overimprovises, tries to control what can’t be controlled. He turns improvisation into a weapon — and that weapon becomes the very thing that destroys him.

How Pacino came aboard: a role that demanded vulnerability, risk, and a rare kind of courage for the time

There’s a well-earned mythology around Al Pacino in this film because Dog Day Afternoon is, more than anything, about someone talking to stay alive. And Pacino here is at a kind of nervous peak: he isn’t performing to be admired; he’s performing like someone trying to breathe.

Getting there, though, wasn’t straightforward. Pacino accepted, backed out, reconsidered, returned — the kind of back-and-forth you get from someone who knew he was walking into an emotionally dangerous place. The character was excessive, vulnerable, and threaded through a theme that, in 1975, mainstream culture still treated as taboo or punchline: the queer dimension of the case, the relationship with Leon (based on Elizabeth Eden), and the fact that the robbery had been linked to the attempt to finance gender-affirmation surgery.

Bregman kept pushing because he understood what the role needed from a star: not “criminal charisma,” not heroism, but something more uncomfortable and rarer — the ability to be erratic without becoming a cartoon, and desperate without apologizing for existing. Lumet, in turn, guarded the film against sensationalism: the focus wouldn’t be moral shock, but human drama, the “cry” underneath the event.

And there’s a casting detail that says a lot about the film’s authenticity: Pacino pulled in actors he had history with — theater people, off-Broadway people, people who knew how to work in nuance without relying on star sheen. John Cazale, for instance, is perfect as Sal because he never tries to “compete”: he’s tense silence, contained threat, a nearly ghostly presence. The film needs that so it doesn’t become Sonny’s one-man show.

Filming: realism as strategy, and why the movie feels like news

Lumet shot the film between September and November 1974 and did something that looks simple but is profoundly calculated: he creates the sensation that we’re watching an event as it happens.

The opening — New York as a living, ordinary, heat-soaked city — functions as a breath before collapse. The absence of a musical score (with only occasional, diegetic exceptions) is a decision of language: music tends to guide emotion. Lumet didn’t want to guide. He wanted the scene to breathe like reality.

The “bank” was built inside a space that allowed movable walls, cameras in impossible positions, and the option to see the street from within. Result: the interior never feels sealed off. The street presses in. And outside, Lumet turns extras and bystanders into a collective organism. The crowd grows, reacts, improvises, becomes a character. The police, too, aren’t an abstract institution: they have faces, fatigue, nerves, ego, bureaucracy.

There’s physical intelligence in the direction: moving cameras, long lenses, a TV-news energy, close-ups that feel like they’re catching thought at the instant it forms. Lumet wanted a newsreel quality — the feeling that the camera is fighting for space, wrestling with chaos.

And there’s also craft built to sell summer heat while shooting in fall: fluorescent light, carefully controlled “sweat” (Lumet mixing water and glycerin), tricks to keep cold from showing (cast members with ice in their mouths to avoid visible breath). None of this is mere behind-the-scenes trivia: it’s why the film feels sticky, claustrophobic, hot. The heat isn’t setting; it’s dramaturgy.

The “Attica!” chant: the moment the film explains the world in a single word

There’s a moment in Dog Day Afternoon that leaps beyond plot and becomes pure social commentary: Sonny steps outside, negotiates with police, clocks the crowd, and turns desperation into rhetoric. “Attica! Attica!” isn’t just a memorable line; it’s an emotional shortcut. The word triggers the fresh memory of the Attica prison uprising and massacre and, with it, a repertoire of distrust toward state violence. Suddenly, the robber isn’t seen only as a criminal: he becomes a symbol, an improvised spokesperson, “the guy who challenges the cops.”

It hits so hard because it reveals a mechanism we now recognize instantly: the public wants a narrative. And when someone offers one, it buys in — even if it’s dangerous, even if it’s contradictory. Sonny understands this intuitively. And the film, by registering that understanding, anticipates our present: an era in which slogans replace argument, crowds ignite around keywords, and spectacle often swallows complexity.

Leon, the phone calls, and the film’s hidden heart

If “Attica” is the public peak, the phone calls are the intimate peak.

Lumet shot the conversations back-to-back, pushing Pacino to emotional exhaustion. And it’s there that the film changes species: it stops being a “heist movie” and becomes, without embarrassment, a relationship drama. What’s at stake isn’t only escape, money, survival. It’s love, fracture, guilt, dependence, a last attempt at repair.

The delicate achievement is how Leon is treated. The film isn’t perfect (it couldn’t be, being made in 1975), but there’s a deliberate effort not to reduce him to cliché. The humor in the conversation isn’t laughter “at” a queer character — it’s laughter at the banal tragedy of a couple who misunderstands each other, loves badly, loses each other. For commercial cinema of the time, that alone is radical.

And this is where Dog Day Afternoon gains depth: Sonny doesn’t rob a bank to become a famous outlaw. He does it because he’s broken, cornered, trying to buy a solution to something the world insists on treating as impossible. The film never asks you to approve the crime. But it demands that you see the human being.

Cazale and the perfect sad joke: “Wyoming”

Another sign that the film breathes life is the kind of detail that arrives through improvisation and stays as a signature. When Sonny asks where Sal wants to run, the answer “Wyoming” is so absurd and so precise it becomes a portrait: the fantasy of escaping to somewhere distant enough to be “outside the world,” as if changing a spot on the map could make despair stop existing. It’s funny — but funny in the way certain things are funny when the situation is already lost: laughter with grief embedded inside it.

The airport ending: when the state decides to end the show

The ride to JFK and the ending are the harsh reminder that behind the theatrical negotiation there’s a machine that, at some point, chooses to conclude the story with force. Sal’s execution is blunt, abrupt, without catharsis. Lumet’s cut avoids sensationalism: he opens the frame, shows the scene as panorama, and leaves us with emptiness. The tragedy isn’t stylized here. It’s administrative.

Reviews, box office, awards: the success of a film that isn’t “easy”

Released in September 1975, the film became both a critical and commercial hit. Reviews praised precisely what could have gone wrong: a tone that blends tension and humor, a disorderly energy that never turns to mess, and the courage to hold a morally ambiguous protagonist with empathy.

The awards confirm the impact: an Oscar for Pierson’s Original Screenplay, major nominations, recognition for the editing, and, decades later, the institutional seal of classic status: in 2009, Dog Day Afternoon entered the National Film Registry as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

But the real measure of its legacy isn’t the trophy. It’s the way the film survives as reference. “Attica” became a cultural quote. The structure of a “public event surrounded by media and crowd” became a template for countless narratives after it. And above all, Sonny as a man in meltdown — irritating, charismatic, cruel, childish, desperate, and human all at once — remains a masterclass in acting and directing.

What 50 years reveal: why the film gets more current with time

Maybe the question isn’t “why is Dog Day Afternoon still relevant?” but “why does it feel more modern every year?” And the answer is in what it understands about us.

It understands that crowds crave spectacle. That police perform, too. That the press amplifies, distorts, canonizes. That a cornered protagonist learns to play with that — and becomes transformed by the game. It understands that “truth” isn’t a solid thing: it’s contested, negotiated, shouted in the street.

And with devastating clarity, it understands that beneath the big event there are small, precarious, intimate lives trying to survive. The robbery becomes “the story of the day.” For Sonny, it’s a last attempt to fix what he doesn’t know how to fix. For Leon, it’s a life exposed as public controversy. For the hostages, it’s trauma. For the city, it’s entertainment. For the state, it’s a problem to be closed.

Fifty years later, we recognize the mechanism with discomfort. Because it didn’t go away. It just changed platforms.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.