With only a few months to go before the release of The Odyssey, the new film by Christopher Nolan, the anticipation surrounding the project has already moved far beyond ordinary hype. This is not merely curiosity about another film by a celebrated director. What is at stake here is something broader: the sense that this film concentrates, within itself, debates about what large-scale cinema can still be — or dares to be.

From the moment it was announced, it was clear that Nolan did not choose The Odyssey on impulse or as a cultural shortcut. The work attributed to Homer is not simply a respectable cornerstone of Western literature; it is a deeply unsettling, ambiguous text that feels strikingly modern in the questions it asks. And that helps explain why it aligns so organically with Nolan’s cinema — perhaps more so than any other ancient epic.

The Odyssey is, above all, a story about time. Not the heroic time of great victories, but the time of waiting, wandering, and prolonged survival. Odysseus spends twenty years away from home: ten fighting in Troy, ten trying to return. By the time the poem begins, he has been gone so long that his identity has turned into myth — and myth, as we know, rarely matches the real man. Nolan has always been fascinated by this gap between lived experience and constructed narrative. His films do not treat time as background, but as an active dramatic force, capable of reshaping memory, identity, and morality.

It is not hard to see why The Odyssey draws him in now. The poem begins in medias res, unfolds through fragments, recollections, and retellings, moving forward and backward rather than in a straight line. The past is unresolved, the present unstable, and the future uncertain. It is a structure that echoes the narrative logic of Memento, Inception, Interstellar, or Dunkirk. Nolan does not seem interested in “updating” Homer, but in listening to what this text still says when read through our own contemporary anxieties.

Odysseus’s journey, so often reduced to a series of monsters and adventures, is in fact a sequence of moral and psychological trials. The Cyclops Polyphemus is not merely a physical enemy; he exposes the hero’s pride and arrogance. The Sirens embody the temptation of forgetting, of abandoning the struggle altogether. Circe and Calypso offer shortcuts — pleasure, rest, even immortality — but at the cost of renouncing one’s own identity. Odysseus’s refusal to live forever with Calypso is one of the poem’s most revealing moments: he chooses finitude, an imperfect return, the pain of time, because that is what keeps him human.

This point has been repeatedly emphasized by those following the project closely: Nolan is not interested in an ornamental epic, but in a profoundly human reading of The Odyssey. A film less concerned with illustrating myth than with examining the psychological cost of survival — especially after war.

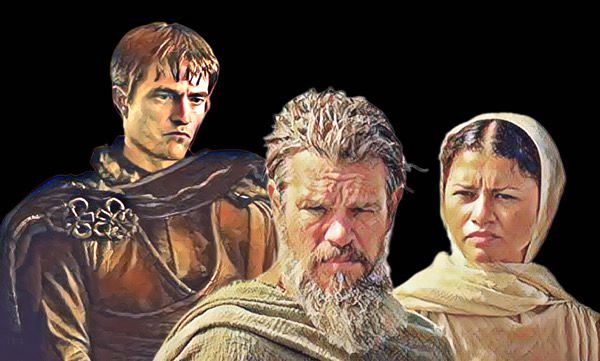

The announced cast reinforces this interpretation. The choice of Matt Damon as Odysseus points to a hero far removed from classical idealization. Damon carries a very specific screen presence: practical men, marked by experience, survivors whose choices leave visible consequences. It is easy to imagine an Odysseus who is weary, strategic, wounded — a man whose intelligence saves him, but whose pride exacts a price.

Around him, the film gathers actors who suggest emotional intensity and ambiguity rather than pure grandeur. Anne Hathaway, a frequent Nolan collaborator, remains shrouded in mystery regarding her role, but her work with the director has consistently involved characters shaped by moral and emotional conflict. Tom Holland appears as a possible embodiment of Telemachus, the son who grows up in the shadow of an absent father — a crucial figure in ensuring that The Odyssey is not only a story about return, but also about forced maturity. Zendaya and Robert Pattinson round out a cast that points toward inner conflict, psychological tension, and a contemporary reading of archetypes.

Specific roles remain under strict secrecy, as is typical for Nolan’s projects, and this only intensifies speculation. Still, a consensus is beginning to take shape: this will not be a classical epic in the traditional sense. Everything suggests an epic of interiority, in which gods and monsters coexist with silence, emotional erosion, and accumulated trauma.

There is also the industrial context — perhaps the most revealing aspect of all. At a time when Hollywood largely bets on serialized franchises, shared universes, and endlessly expandable narratives, Nolan is investing in a self-contained film based on classical literature, with a major-studio budget and clear auteur ambition. That alone turns The Odyssey into more than a highly anticipated release: it becomes almost a political gesture within the industry, a reaffirmation that cinema can still be large-scale, demanding, and unapologetically adult.

What has been said behind the scenes reinforces this perception. The Odyssey reasserts Nolan’s belief in cinema as a physical, collective experience — something that requires attention, commitment, and even discomfort. As with Dunkirk or Oppenheimer, there is no expectation of a film that explains everything or guides the viewer gently by the hand. The bet is on image, sound, and editing as narrative tools, not decorative ones.

Perhaps that is why the project resonates so directly with our present moment. We live in an era marked by prolonged wars, displacement, endless waiting, and fractured identities. The Odyssey, written nearly three thousand years ago, speaks precisely to these conditions. Odysseus’s return is not a simple celebration; it is a confrontation with what has been lost, what has changed, and what cannot be restored. Penelope, in turn, is not merely the faithful wife, but a strategist of waiting — someone who has also survived time and absence.

In the end, the anticipation surrounding The Odyssey may have less to do with curiosity about how Nolan will film monsters, gods, or battles, and more to do with the feeling that this film is attempting to answer — through the language of cinema — an ancient and still urgent question: who are we after we have endured everything?

If cinema can still be a space for this kind of adult, dense, and unsettling reflection, The Odyssey seems determined to remind us that it can.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.