There are directors whose films must be digested, and, for many audiences, that usually sounds like a flaw. With Paul Thomas Anderson, it has always been the opposite. Discomfort is the method. Anderson has never made films to reassure viewers; he makes films to unsettle them. Over nearly three decades, he has built a body of work that consistently provokes, exhausts, irritates, and mesmerizes — often all at once.

Among today’s major auteur filmmakers, Anderson may be the one who most fully embraces cinema as friction. From the beginning, he showed little interest in tidy narratives or explanatory arcs. His films thrive on excess, emotional abrasion, and obsessive repetition of gestures, conflicts, and power dynamics. Above all, he is an actor’s director, one who knows precisely how to push performers toward their most revealing work.

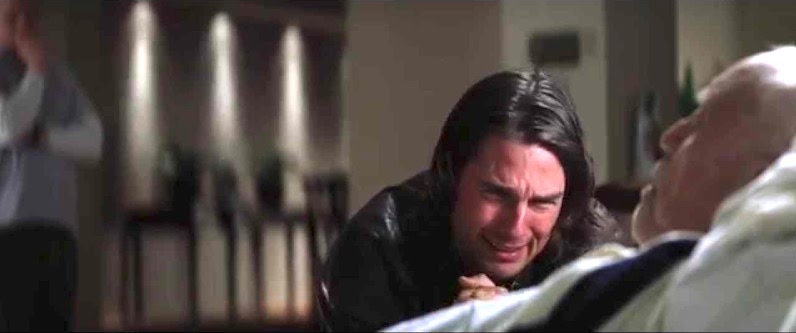

It is hard not to think about “lost” Oscars when revisiting his filmography. Tom Cruise was never more raw or ferocious than in Magnolia. Joaquin Phoenix delivered, in The Master — years before Joker — one of the most unsettling performances of the century, opposite a towering Philip Seymour Hoffman. These performances are no accident. They emerge from a director who trusts discomfort, silence, and instability as creative tools.

Anderson arrived early with almost arrogant confidence. Boogie Nights already displayed his fascination with dysfunctional communities, characters on collision courses, and camera movements that signal complete command of cinematic language. Magnolia expanded that into a fragmented emotional epic, while There Will Be Blood cemented his harshest signature: power as corrosion, isolation as destiny, violence as grammar. The Master pushed this even further into abstraction, where psychology takes precedence over plot. Even when he appeared lighter, as in Licorice Pizza, Anderson never abandoned strangeness — he simply cloaked it in nostalgia and humor.

His latest film marks a return to the most radical version of PTA, seemingly indifferent to whether audiences “get it.” The dominant critical question is blunt: What is the story? There is no conventional plot, no clear progression, no comforting arc. What exists instead is a relentless succession of confrontations — one battle after another, with no pause for relief.

Yet to claim the film has “no story” is a mistake. The narrative, though original, is clearly inspired by Vineland by Thomas Pynchon. Anderson does not adapt the novel so much as uproot it from the past and replant it in the present. He dispenses with flashbacks, refuses nostalgic distance, and turns memory into a weapon. The past does not explain itself here; it interrupts. “One battle after another” becomes not just a structure, but a historical condition. Repression does not end revolt; it reorganizes it.

There is, in fact, a powerful and deeply tragic narrative thread. At its center is a reckless radical rebel who ignites passion in both the idealist and the enemy. Her actions fuel desire, loyalty, and rivalry, but they also carry irreversible consequences: separation from her daughter, raised alone by her former partner, far from the militant world that once defined them. Fifteen or sixteen years later, nothing has been resolved, only displaced.

This is where the film reveals its cruelest mechanism. In the case of Willa and Bob, there is a vital secret — withheld from the audience for much of the runtime — that, once revealed, changes everything. Perfidia Beverly Hills emerges as the film’s moral axis, in an extraordinary performance by Teyana Taylor. Perfidia is neither romanticized nor punished as a cautionary emblem. She is contradiction incarnate: militant and maternal, seductive and destructive, capable of tenderness and absolute abandonment. The image of a pregnant Perfidia firing a machine gun is not provocation for its own sake; it is the film’s thesis in a single shot. Revolution does not pause for motherhood; motherhood does not survive revolution unscathed.

Once Perfidia disappears, her absence shapes everything that follows. The secret driving the final act never becomes spectacle; it infects. Anderson’s refusal to foreground it is precisely what makes the choice devastating. It is a risky narrative move, and one only he could sustain.

Much of the nearly three-hour runtime follows Willa fleeing while Bob desperately chases after her. Bob is kind-hearted, but worn down by time, exile, and historical defeat. He has forgotten passwords, codes, and rituals of his guerrilla past. Leonardo DiCaprio turns this erosion into something both funny and painful. The humor does not soften the blow; it exposes it. Bob is not a fallen hero, but a father scrambling to protect his daughter while barely understanding the battlefield he has re-entered.

Alongside him, Benicio Del Toro appears as an unexpectedly serene guide through underground networks of survival, each scene hinting at entire unseen worlds. Sean Penn begins almost cartoonish, and that is the trap. Gradually, Lockjaw becomes deeply disturbing, blending fanaticism, decay, and moral emptiness into a figure that inspires fear, revulsion, and, disturbingly, pity.

The final hour, dominated by confrontations, is exhilarating and brutal. Visually, Anderson’s control is absolute. Shot in VistaVision yet stripped of classical grandeur, the film favors urgency over awe. Bodies tell the story. Generations collide. Chaos is choreographed.

What doesn’t work for me? The excessive use of Jonny Greenwood’s score, which at times overstates what Anderson’s images already convey with brutal clarity. And, as so often in contemporary auteur cinema, the length. Nearly three hours of “one battle after another” can be exhausting. The impact might have been even stronger at two.

Still, One Battle After Another asserts itself. It is a political epic that is, at its core, a film about fatherhood. Furious, exhausting, and unexpectedly tender. In a cultural moment hostile to political mythmaking on this scale — and suspicious of intelligence in blockbuster form — Paul Thomas Anderson insists. He does not offer solutions. He offers an inheritance. And he suggests, quietly and radically, that survival itself can be a form of resistance.

For all these reasons, the film already stands as one of the strongest contenders for the 2026 Oscars — not despite its excesses, but because of them.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.