When Goodbye June places “if there are any heavens”, by E. E. Cummings, at the center of a mother-and-son farewell, the choice is anything but decorative. It arrives precisely when belief systems fail, and everyday language collapses. What Cummings offers is not comfort or promise, but recognition. If there are heavens at all, they are not granted by doctrine; they are the quiet consequence of a life lived with care and ethical presence.

That gesture says as much about the film as it does about the poet. Because Cummings always wrote from a place of suspicion toward structures that try too hard to explain what can only be lived.

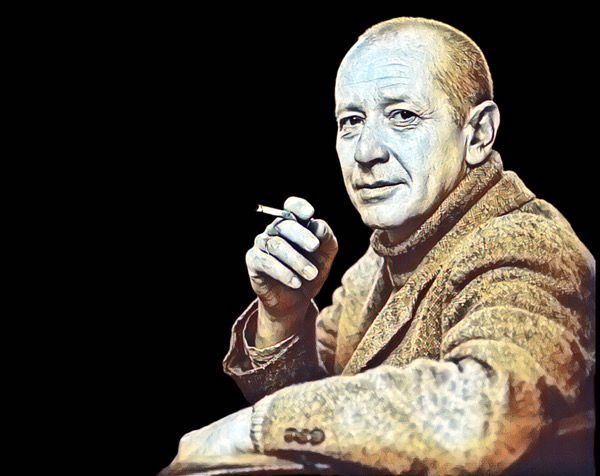

Born in 1894 in Cambridge and educated at Harvard, Edward Estlin Cummings crossed the twentieth century as a poet, painter, essayist, and playwright. His biography is often reduced to typographic eccentricities, but one experience organizes everything: World War I. Serving as an ambulance driver in France, he was unjustly arrested and detained for months. He returned convinced that official language — the language of the state, of patriotic rhetoric, of ready-made moral certainty — could flatten the individual as efficiently as any weapon.

From that point on, his poetry became a form of resistance. Not pamphleteering resistance, but an intimate one. A refusal to write as expected, to punctuate according to manuals, to arrange the world in sentences that look correct yet feel lifeless.

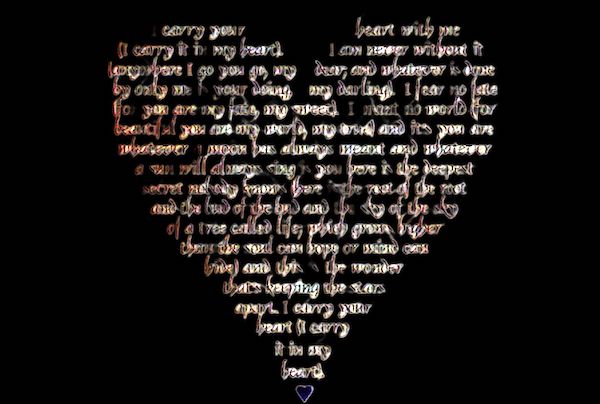

This is where the visual dimension of his poetry becomes essential rather than incidental. Cummings’ innovation was not only verbal or musical, but visual and spatial. His poems ask to be seen before they are understood. The white space of the page becomes expressive. Words approach or retreat, lines fall, breathing patterns emerge, and interruptions matter.

Punctuation organizes breath as much as syntax. Lowercase letters reject visual hierarchy and institutional authority. Parentheses introduce parallel thought rather than explanation. Reading becomes movement through space, not linear consumption.

This was no accident. Cummings was also a visual artist, trained in composition and deeply attentive to form. In poems like “l(a”, the fragmentation of the word loneliness allows the reader to see solitude before grasping it intellectually. The poem conveys feeling rather than describing it. Unlike traditional calligrams, Cummings’ work is kinetic. Meaning unfolds through motion, pause, and visual rhythm, almost like a minimalist choreography.

This helps explain why his poetry translates so naturally to cinema. Film, too, depends on time, silence, and what remains unsaid. When films turn to Cummings, they do so at moments when dialogue would feel excessive. His poems function like inner monologue, like letters never sent, like charged silence.

In In Her Shoes, “i carry your heart with me” marks an emotional rite of passage, a hard-won voice finally spoken aloud. In Hannah and Her Sisters, “somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond” becomes borrowed language for desire, both masking and revealing moral complexity.

And when Goodbye June returns to “if there are any heavens”, the circle closes. This is Cummings at his most radical and most restrained. A poet who does not declare but questions. Who does not promise but observes. Who shifts heaven from theology to lived experience. The mother in the poem is not canonized; she is recognized. Her life itself becomes the argument.

Everything in Cummings ultimately leads back to this refusal of ready-made forms. He did not want language to organize life; he wanted life to disrupt language. Words fall apart, gather, touch. Reading demands presence and attention.

That is why, decades later, his poetry still finds its way into film, design, and contemporary visual culture. Cummings understood something early that we are still learning: feeling is not only something we hear or comprehend. It is also something we see.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.