Over more than 30 years of her career, Kate Winslet has been a near-unanimous presence when it comes to acting talent. Nominated for an Oscar almost from the very beginning—already with her second film, Sense and Sensibility—she has built an undeniably enviable body of work.

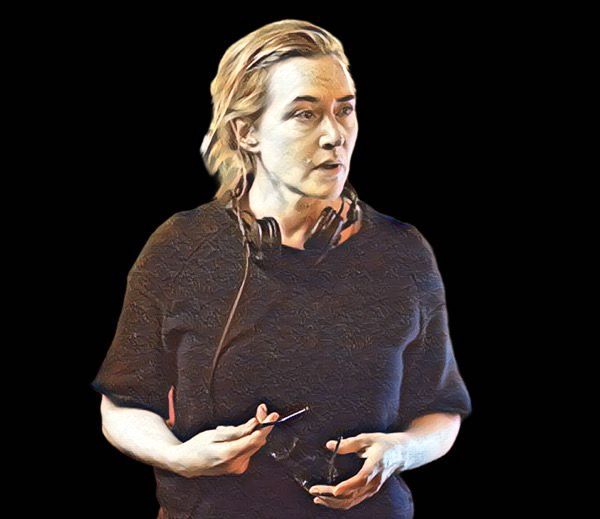

That she would eventually step behind the camera always seemed like a safe bet. The real question was different: what would Kate Winslet be like as a director?

Her debut feature arrives on Netflix as a kind of Christmas gift: Goodbye, June. Known for its intense dramas, it comes as no surprise that the story is designed to make us cry during the holiday season. After all, farewells and nostalgia often accompany the calendar as it forces us to acknowledge that another cycle has come to an end. Not everyone walks with us to the finish line, just as we also say goodbye to others along the way. What stands out here is Winslet’s sensitivity in choosing a story that reinforces the everyday practice of affection, listening, and presence.

In addition to directing, Winslet also stars in the film, and this overlap of roles does not feel like control, but involvement. Goodbye, June is clearly a project guided from the inside out, led by someone who understands that stories about grief demand intimacy, time, and care—both on the page and on set.

The plot unfolds in the days leading up to Christmas, when a sudden decline in June’s health (Helen Mirren) forces her four adult children to gather at the hospital. Julia (Winslet), Helen (Toni Collette), Molly (Andrea Riseborough), and Connor (Johnny Flynn) must put old tensions on hold to face something none of them quite knows how to name: the imminence of loss. Alongside them is Bernie (Timothy Spall), a disoriented father caught between profound love and a very real inability to accept the end.

The script by Joe Anders—Winslet’s son with Sam Mendes—springs from a personal memory but expands into something universal. Anders writes a story about death that refuses to be somber. Humor runs through the film as a survival mechanism, not as a calculated release. And this is central: Goodbye, June understands that grief rarely manifests in an “appropriate” way. It slips, stumbles, and laughs at the wrong moment.

June herself is the key piece in this emotional machinery. She is not merely the sick mother around whom everything revolves. With sharp irony, disarming honesty, and a lucidity that asks no permission, she orchestrates her own farewell. She decides how she wants to be remembered and how her final days should be lived. Helen Mirren builds this woman without excessive sentimentality—firm, loving, and, above all, active until the very end.

As a first-time director, Winslet makes choices that reveal a very clear cinematic vision. The set was designed to encourage vulnerability: a reduced crew, discreet equipment, actors individually miked, and cameras positioned so that the technical presence would nearly disappear. The priority was to create an atmosphere of absolute trust. It’s no coincidence that the performances feel unguarded, as if the film were less interested in “scenes” and more in moments.

This ethic of care extends to the creative team as well. Producing the film alongside Kate Solomon, her partner on Lee, Winslet consciously chose to open space for new talent. Composer Ben Harlan delivers his first film score; Alison Harvey makes her debut as production designer; Grace Clark leads her first project as head costume designer. This is more than a behind-the-scenes detail—it’s a statement. “I believe in lifting people up. Everyone has to start somewhere,” Winslet has said, and that belief echoes throughout the film.

The moment when Connor reads to his mother the poem “If There Are Any Heavens,” by E. E. Cummings, neatly captures the film’s logic: delicacy without solemnity, emotion interrupted by humor, silence respected. Soon after, laughter breaks in almost as an involuntary reflex—because that is how grief often works.

When it becomes clear that June will not make it to Christmas, the family brings the holiday forward and turns the hospital into the stage for “the best Christmas in the world.” There are costumes, children, and an improvised nativity play. Surrounded by her children, grandchildren, and the continuity of life, June dies—not as an abrupt rupture, but as part of a collective gesture of love.

By making her directorial debut with a story about endings, Kate Winslet seems to offer a quiet statement about the act of creating itself: directing, too, is an act of presence. Goodbye, June offers no easy answers or uplifting speeches. It simply reminds us—with rare honesty—that a good farewell does not erase pain, but forces us to love better while there is still time. And that perhaps Christmas exists precisely for this: to bring us together, if only for a moment, around what truly matters.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.