In Stranger Things, numbers were never just numbers. They have always functioned as a subterranean language, a symbolic architecture underpinning narrative, emotional, and moral decisions. There are monsters, portals, and scares, of course, but symbolism has always occupied center stage — in board games, in science classes, in seemingly innocent books, and in the repetition of certain numbers. What appeared to be detail was, more often than not, foundation. That is why the series’ ending cannot be fully understood without taking seriously what Stranger Things has always done best: thinking of the world as a system and asking who is left outside it.

So when the final season reveals that Vecna needs twelve children, the question is not “why so many?” but why this number specifically. And, more importantly, why that number only works once 11 has been neutralized.

Twelve has always been the number of closed orders. It organizes time, the sky, the complete cycle. Twelve months, twelve zodiac signs, twelve hours. When something reaches twelve, it ceases to be a fragment and becomes a system. That is why twelve has historically appeared as a founding number: apostles, councils, orders. Twelve legitimizes. It suggests totality, stability, and destiny. Vecna understands this with unsettling precision. His project is not to destroy the existing world, but to replace it with one that functions without noise. To do that, he needs a number that symbolizes completeness, but a completeness without the individual.

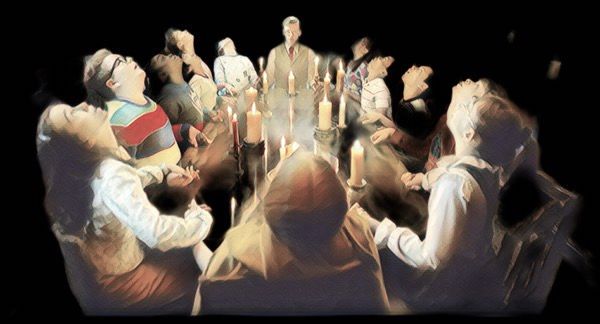

The twelve children are not chosen merely as sources of energy. They form a psychic chorus, a stable field capable of sustaining the continuous spell that draws worlds together. One mind amplifies. Two echo. Twelve stabilize. With twelve, horror stops being an eruption and becomes a structure. Evil ceases to be an exception and turns into a system.

But Stranger Things never operates on a single level. What makes this choice truly disturbing is how it stands in opposition to 11.

If twelve closes the world, eleven is the number that prevents closure. Historically, eleven represents excess, deviation, the transgression of perfect harmony. It exceeds ten — the number of law and moral completeness — without reaching the stability of twelve. Eleven is restless. It does not fit. It remains. It fails to become a system.

None of this is accidental when we think of Eleven.

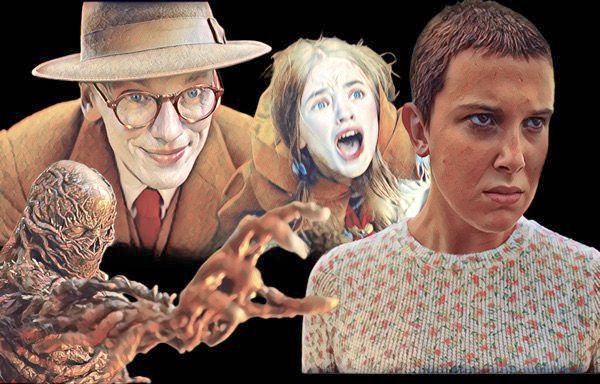

Eleven is not merely a numbered child. Within systems that attempt to turn people into function — like those created by Dr. Brenner and Dr. Kay — she is the “error” that escapes calculation, the exception that should not exist. Narratively, we know Eleven is not a defect. But from the antagonists’ point of view, she is where their plan’s failure becomes visible, because she exposes the moral bankruptcy of that logic. Eleven insists on existing as a subject. That is why she can never be integrated into a chorus. She has always been singular, and it is precisely that singularity that threatens any attempt at absolute order. Vecna understands this. And that is exactly why he does not try to use Eleven.

This is where Holly enters, and where the symbolism of eleven reaches its cruelest point.

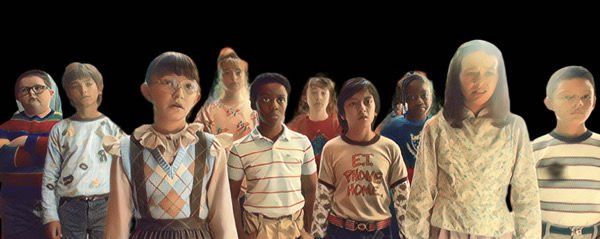

If Eleven is the irreducible eleven, Holly is the capturable eleven. She occupies the same symbolic space — that of passage, transition, the still-open boundary — but without the resistance Eleven has built over time. In Stranger Things, children have not yet “closed” the world. Identity, desire, and fear are still forming. That is why Vecna chooses children: they can still be shaped. They can still be convinced that they belong to something greater.

The system of twelve needs eleven to function, but it cannot tolerate eleven free. Vecna’s move is a mathematical and symbolic perversion: he simulates eleven within the structure of twelve. Holly does not complete the chorus; she opens the bridge. She is the point of traversal, the emotional and psychic trigger that allows a closed system to become expansive. It is no coincidence that she almost crosses back. No coincidence that her fall becomes the most physical image of worlds colliding. Eleven is always the number of the “almost”.

Eleven and Holly thus become mirrored images of opposite fates. Eleven turns deviation into identity. Holly experiences deviation as vulnerability. Vecna cannot defeat Eleven on the terrain of singularity, so he creates a shortcut: he uses Holly to occupy the place Eleven refuses to take. It is a cruel substitution, and perfectly consistent with the villain’s logic.

This is where the series’ ending finds its hardest coherence. The final sacrifice is not mere melodrama; it is a symbolic consequence. Systems built on twelve do not allow a remainder. For the bridge to fall, something must refuse to be part of the totality. Something must remain outside or vanish with it. The cost is not moral; it is structural.

Although the group has not yet fully grasped this, Eleven has already made her decision in silence. Not as spectacular heroism, but as an act of refusal. She accepts disappearance to prevent any world from ever functioning according to the logic of Vecna, Brenner, and Kay. By removing herself, she breaks the logic of twelve and prevents the perpetuation of the twisted reality the antagonists seek to impose.

That is why Stranger Things gestures toward an ending that may not lie in the promise of order, but in the acceptance of noise. Will it?

If so, the series will have told an ancient story in pop form: every promise of a perfect world demands erasure. Every absolute order requires the end of singularity. Eleven wins precisely because she refuses to close the system. And perhaps this is Stranger Things’ most radical idea: the world only remains possible as long as something is left incomplete.

Personally, I think it would be a beautiful ending. But given how often the heroes have been spared, I remain doubtful that the Duffer Brothers will resist the pull of a happy ending — with a door left open for continuation, of course, very much in keeping with the genre. We’ll find out on December 31. Before the end of the 12th month of 2025.

Isn’t that brilliant?

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.