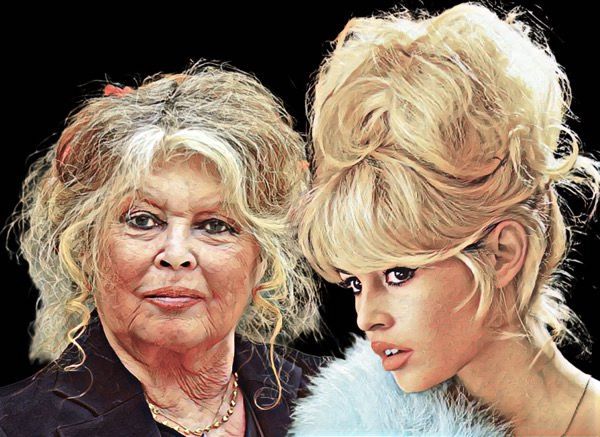

The death of Brigitte Bardot at 91 brings to a close one of the most transformative — and hardest to assimilate — trajectories in the history of 20th-century cinema. The confirmation came this Sunday (28) through the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, which she founded in Paris. Reclusive for decades and voluntarily withdrawn from the spectacle of public life, Bardot was no longer a visible presence. But she remained a symbol of aesthetic rupture, bodily freedom, and a set of contradictions that accompanied her to the very end.

Brigitte Bardot was not merely a star; she changed our gaze.

The birth of a new eroticism

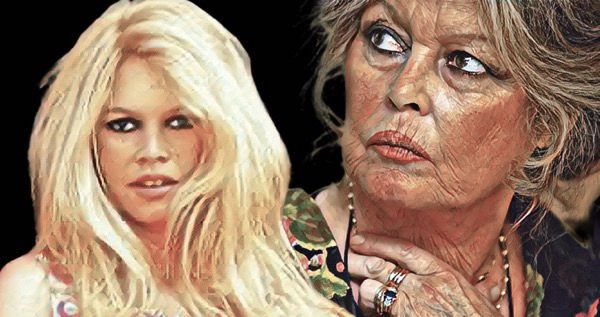

When she emerged in the 1950s, cinema still treated sex as a carefully controlled insinuation. Bardot appeared as a body that did not apologize, did not justify itself, and did not seem to exist in order to be morally corrected. Her image — deliberately tousled hair, heavily lined eyes, a mouth permanently poised in provocation — quickly became cultural language.

The turning point was And God Created Woman, directed by Roger Vadim, then her husband. Released in the United States in 1957, the film was dismissed by many critics but made an immediate impact on audiences. Bardot was 23 when she became an international star. Bosley Crowther, writing in The New York Times, called her “a phenomenon you have to see to believe,” even as he found the film itself weak.

It was not the work that mattered. It was her.

Bardot’s character did not merely desire; she claimed desire as a narrative engine. Simone de Beauvoir saw in this an attempt — however unsuccessful — to confront the tyranny of the patriarchal gaze imposed by the camera. A “noble failure,” she wrote. Cinema was not ready. Neither was the world.

Absolute icon, and prisoner of her own image

Unlike other sex symbols of the era, Bardot did not seem shaped by a studio. Her sexuality was direct, awkward, restless. That made her irresistible and unbearable for the logic of the industry. Nearly everything about her was copied: the messy hair, the heavy eyeliner, the tight clothes, the flounced skirts, the legs perpetually exposed to the sun.

She was not simply a popular actress. She was a behavioral model.

But the cost was high. Bardot never romanticized her fame. She attempted suicide for the first time while still very young, facing her parents’ rejection of both her acting ambitions and her relationship with Vadim. Throughout the 1960s, she lived under relentless press persecution, invasions of privacy, abusive relationships, and profound emotional exhaustion.

In 1960, on her 26th birthday, she attempted suicide again.

The freedom she projected on screen did not translate into peace off it.

The red ballet flat: when style becomes cultural language

There is a seemingly small detail that helps explain why Brigitte Bardot transcended cinema and became language: the ballet flat.

It was Bardot who transformed the Repetto ballet flat — originally created for dancers — into an object of urban desire. The story begins before cinema: trained in classical ballet, Bardot was familiar with the brand founded by Rose Repetto, mother of choreographer Roland Petit. But the decisive gesture came when she began wearing, outside the studio and the stage, the red ballet flat created especially for her.

Simple, comfortable, flat, almost childlike, and radically anti-glamour by the standards of the time.

In a world where femininity was still associated with high heels, rigidity, and constant performance, Bardot appeared in ballet flats as if making a silent declaration: the body does not need to suffer to be desirable. The choice resonated with everything she represented — freedom of movement, refusal of excessive artifice, sensuality without theatricality.

The red Repetto flat became a symbol of a new kind of elegance: spontaneous, accessible, corporeal. Like her disheveled hair and heavy eyeliner, the shoe ceased to be an accessory and became a cultural code. Bardot helped take ballet off the stage and onto the street, anticipating what we now call “effortless” fashion: a notion that was deeply subversive in the 1950s and 60s.

Decades later, Repetto would reissue the model repeatedly, always directly linked to Bardot’s name, not as empty nostalgia, but as recognition that the object carries a historical turning point: the moment when comfort, freedom, and femininity ceased to be opposites.

Like Búzios, like her early abandonment of cinema, like her refusal of the star system, the red ballet flat belongs to the same larger gesture: Bardot did not dress to please, she dressed to exist.

Bardot in Brazil: refuge in Búzios

In 1964, fleeing the suffocating scrutiny of the European press, Bardot came to Brazil accompanying her Brazilian boyfriend, Bob Zagury. Her destination was then a discreet fishing village on the coast of Rio de Janeiro: Armação dos Búzios.

Bardot’s time in Búzios was not a footnote; it was foundational. For the first time in years, she was able to move with a degree of anonymity: barefoot, without makeup, talking to locals, far from the machinery of the star system. There, Bardot was no myth.

The impact was immediate and lasting. Her presence placed Búzios on the international map and permanently transformed the destination. Decades later, the Orla Bardot would memorialize that passage not merely as a tourist tribute, but as the symbol of a moment when the most photographed woman in the world chose Brazil in order to disappear, briefly, from the gaze.

This episode explains her trajectory better than many of her films: Bardot did not seek adoration. She sought silence.

Leaving the cinema at the height

In 1973, at 39, Brigitte Bardot did something almost unthinkable: she abandoned cinema. It was neither a decline nor a lack of offers. It was a conscious refusal. Her last significant appearance came that same year. The decision was final.

“I knew my career was based entirely on my physique,” she would later say. “I decided to leave the way I always left men: first.”

Few stars have had the courage — or clarity — to break away like that.

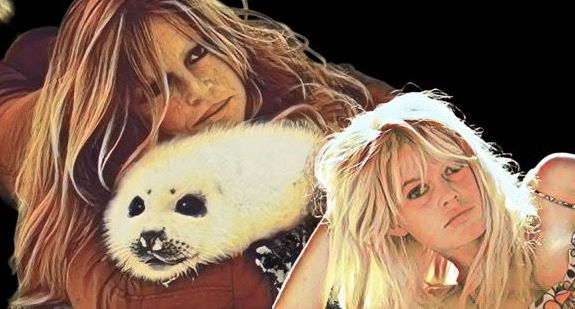

A second life: animals at the center

Even before leaving the cinema, Bardot had begun to engage with animal causes. But it was only in 1986 that she turned this commitment into an absolute mission, founding the Brigitte Bardot Foundation. To ensure its financial survival, she auctioned off jewelry and personal belongings.

From then on, she devoted herself entirely to animal welfare: fighting the use of fur, denouncing wolf hunting, bullfighting, vivisection, and the consumption of horse meat. She confronted governments, cultural traditions, and economic interests with tireless — and often solitary — militancy.

“I gave my beauty and my youth to men,” she once said. “Now I give my wisdom and experience to animals.”

A legacy strained by politics

In her later decades, however, Bardot’s public image underwent a profound shift. Statements attacking immigrants, Muslims, and the LGBTQIA+ community led to five convictions for inciting racial hatred. In books and interviews, she adopted an alarmist, exclusionary discourse, aligning herself with the French far right and publicly supporting Marine Le Pen.

She also positioned herself against the #MeToo movement, calling allegations of abuse “hypocritical” and “ridiculous.” For many, this marked a painful rupture with the symbol of freedom she had once represented. For others, it confirmed that Bardot had always been unclassifiable — and uncomfortable.

A legacy without easy absolution

Brigitte Bardot leaves behind more than 50 films, an incalculable aesthetic influence, and a legacy that resists easy readings. She permanently changed the way cinema filmed female desire. She also showed how myth can become a prison, and how refusal can be the most radical form of freedom, yet she ended her days associated with extreme conservatism.

“With me, life was always made of the best and the worst,” she once said. “Everything was excessive.”

Perhaps that is the most precise definition of her life.

Descubra mais sobre

Assine para receber nossas notícias mais recentes por e-mail.